The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (6 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Lhuyd put years of his life into field and library research on the syntax and lexicons of the languages of Wales, Ireland, Scotland, Cornwall and Brittany, both historical and modern. Actually he owed some of his impetus and inspiration to the work of a Breton, Paul-Yves Pezron, who published a book entitled

Antiquité de la nation et de la langue des Celtes, autrement appelés Gaulois

in 1703.

7

Lhuyd apparently helped as an entrepreneur in arranging swift translations of Pezron’s work into English and Welsh. The English translation appeared in 1706 under the title

The Antiquities of Nations, More particularly of the Celtae or Gauls, Taken to be Originally the same People as our Ancient Britains

, only a year before Lhuyd’s own magnum opus,

Archaeologia Britannica

.

8

The creative extension of Pezron’s French title in its translation into English is telling, and summarizes the two basic hypotheses shared by the two men. One of these extended the application of the ‘Celt’ terms, beyond the meanings given them by the ancients, to include the people and languages of the British Isles. In other words, these eighteenth-century bookworms created the concept of

insular Celts

.

9

The other, less justified hypothesis was the implicit assumption that all ‘Ancient Britons’, including those previously living in England, were celtic-speaking. Crucially, no mention was

made of a Central European homeland. Although their work was a milestone in historical linguistics, it should be remembered that neither of the hypotheses was new; the Scottish scholar George Buchanan had suggested both ideas previously in outline as early as 1582.

10

Unlike Pezron and Lhuyd, however, Buchanan had made a more objective and systematic analysis of all the classical sources, and had even tried to marshal evidence for an ancient celtic-speaking England, from place-names and standard Roman sources such as Tacitus, Strabo, Ptolemy and Caesar.

Buchanan had also linked north-west Spain with Ireland and northern England on the basis of the respective tribal names – Brigantia and Brigantes – assigned by Ptolemy during Roman times. Buchanan argued for three related ‘Gallic’ dialects spoken during classical times in the British Isles: Belgice, spoken in northern Gaul and south-east England; Celtice, spoken in Spain, Ireland and Scotland; and Britannice, a language ancestral to Welsh.

11

Simon James speculates at length on the reasons for Lhuyd’s choice of the term ‘Celtic’ rather than ‘Gallic’, implying that this was a pivotal decision that gave rise to later myths. He suggests Lhuyd’s own nationalism, the recurrent poor relations between the French and the English, and the coincidence of the date of publication of Lhuyd’s own book with the Treaty of Union between England and Scotland as possible factors in this decision and in the subsequent explosion of popular interest in things Celtic.

12

But this emphasis on the origin and effect of opting for the ‘Celtic’ rather than the ‘Gallic’ label, and Lhuyd’s contribution to it, all seems to me perhaps laboured, or at least a polemic

decoy. Disembodied slogans do not work alone. If the concept of an insular-Celtic or Breton Gallic heritage was a mere fad of the Enlightenment and Romantic eras, it would have died long ago and would have no continuing popular resonance, let alone the power to survive in the names of British football teams and the modern French cartoon characters Asterix and Obelix. Whatever his supposed motives or inaccuracies, Julius Caesar had already made the connection between language and the terms ‘Celtae’ and ‘Galli’, nearly two thousand years before, in the first paragraph of his famous campaign epic

Gallic Wars

(see p. 10). Both Lhuyd and Pezron seem to have been even-handed, whether one agrees with them or not, in using the terms ‘Celtic’ and ‘Gallic’ interchangeably. Given the classical texts available then, as today, the hypothesis of the geographical relationship between Ancient Celts and the celtic languages of Brittany and the British Isles was a reasonable provisional interpretation of new linguistic data.

What has always been lacking is a systematic testing of the linguistic model against alternative scenarios for the geographical origins of the Ancient Celts and the cultural relevance of celtic languages. The dominant view over the past 150 years has been that Celts had their origins in the Iron Age cultures of Central Europe. Although apparently the more glaring howler, this does provide such an alternative scenario for systematic comparison. James

13

is less ready to name and shame his archaeological colleagues and forebears of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries for perpetuating that leap of imagination than he is to lampoon Lhuyd. The Central European homeland theory cannot be put at Lhuyd’s door, although he did believe in Iron Age migrations to Britain. Luckily, this alternative model is

independent of the linguistic question, thus reducing the overlap of evidence and the opportunity for circular reasoning.

After many pages on Lhuyd, Simon James has this to say on the Central European Iron Age connection:

During Victorian times, as scientific excavation began to develop, major discoveries in mainland Europe were ascribed, with considerable confidence, to the continental Celts or Gauls of the classical texts. Of particular importance, were the finds in Hallstatt in Austria and La Tène in Switzerland. At Hallstatt, many richly furnished Early Iron Age graves were excavated. The finds proved to be related to material from a wide region north of the Alps, and seemed to correspond in time and place to the earliest Greek references to

Keltoi

(around the sixth century

BC

).

14

He goes on to describe similarities between some of these cultural finds and burials in eastern France and the Rhine basin, and adds:

Again on grounds of date and geographical location, these remains were identified with the Celts or Gauls which classical sources reported had poured into Italy from just these areas around 400

BC

. The unique traits of the artefacts … became identified with Celtic Gaulish peoples, and the areas … thought of as ‘Celtic homelands’.

15

Now James is clearly not impressed by the quality of evidence for these connections, but he devotes much less space to exploring the story of this archaeological inference than he does to Lhuyd. Nor does he cite the relevant classical references used for constructing this part of the Celtic myth. From my reading of his argument and those of other Celto-sceptic

debunkers, however, the Central European homeland story was the weakest link in the chain of the insular-Celtic identity construction, when compared with the linguistics and requires most careful testing.

Since evidence for the supposed homeland of the Celts is central to the story of British origins, I rang Simon James to ask him how on earth anyone could have come to the conclusion that the Celts originated in Central Europe. More specifically, I mentioned Herodotus and asked him which classical sources, imputed in his book, had been used by archaeologists to place Celts north of the Alps in Central Europe.

As I already suspected, the main sixth-century

BC

‘source’ was the grand historian himself, Herodotus, who, in a discussion on the difficulty of measuring the length of the Nile, demonstrated in a passing comment how little he knew about the source or course of the Danube:

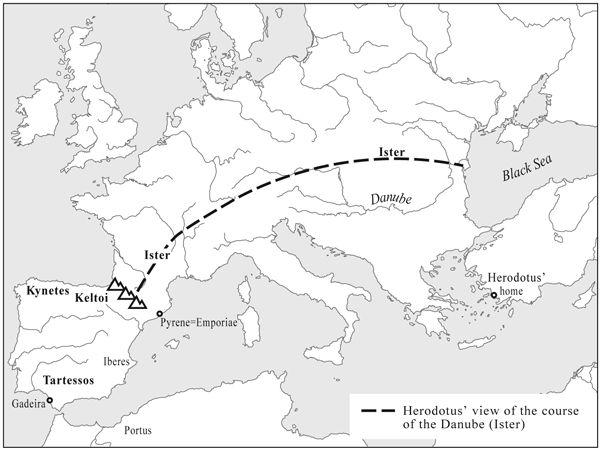

[The Nile] starts at a distance from its mouth equal to that of the Ister [Danube]: for the river Ister begins from the Keltoi and the city of Pyrene and so runs that it divides Europe in the midst (now the Keltoi are outside the Pillars of Heracles and border upon the Kynesians, who dwell furthest towards the sunset of all those who have their dwelling in Europe).

16

In this quote Herodotus is clearly talking about Iberia in southwest Europe, but mistakenly thinks that it held the source

of the Danube. In published reconstructions of Herodotus’ distorted view of the route of the Danube through Europe, historical geographers have uniformly taken ‘Pyrene’ to refer to a Pyrenean rather than Central European location. Avenius (Proconsul of Africa,

AD

366) in his description of the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts of south-west Europe (in which he also discusses the Celts),

17

mentioned the port of Pyrene as being near Marseilles. Livy also mentioned ‘Portus Pyrenaei’.

18

Both writers were probably referring to the Roman port later popularly known as Emporiai (meaning ‘markets’) situated at the eastern end of the Pyrenees – now the Spanish archaeological site of Ampurias.

19

This is the simplest explanation, consistent with three of four geographical locators, for Herodotus’ western or Iberian source of the Danube, implicit in his statement. These three locators are the Latin name for those mountains, Montes Pyrenae, and Herodotus’ two statements that ‘Keltoi are outside the Pillars of Heracles’ – i.e. beyond Gibraltar – presumably on the Atlantic coast of Iberia – ‘and border upon the Kynesians, who dwell furthest towards the sunset of all those who have their dwelling in Europe’ – i.e. the Kynesians (referred to in other writings as the Kynetes, Cynesians or Conios) lived at the westernmost point of Europe, in south-west Iberia. This third locator fits with other authors’ statements that the Kynetes were neighbours of Tartessus (i.e. north-west of Gibraltar in the Gulf of Cadiz).

20

The fourth and least credible locator is, of course, the geographical source of the Danube, which, from the first three locators, Herodotus incorrectly thought to rise in the Pyrenees. Nineteenth-century historians were well aware that the source of the Danube is in Germany and should have recognized the

inconsistency. Unsurprisingly, Herodotus did locate the mouth of the Danube correctly – discharging into the Black Sea, much nearer to his own home – and did acknowledge that his information for the rest of the Danube’s long course in Europe was second-hand from other sources (

Figure 1.1

).

It is clear that the inference from this passage in Herodotus that Celts came from Central Europe is at best wishful thinking and at worst deliberate distortion. The more rational view of Herodotus’ description is obviously that Celtic lands were in south-west Europe and he had got both the course and source of the Danube wrong. This puts those nineteenth- and twentieth-century archaeologists out on a very shaky limb – and not the same one Buchanan, Pezron, or Lhuyd were sitting on. The view that there was a connection between celtic languages and the classical Celts is consistent with Herodotus’ statement of proximity to the Pyrenees and with the good evidence that celtic languages were spoken in France and Spain during early classical times.

Figure 1.1

Which Danube? Herodotus lived in Halicarnassus, and his knowledge of Western Europe was sketchy. Although he realized that the Celts were far to the west, near the Pyrenees, he mixed this location up with the actual source of the Danube in Central Europe. This mistake unwittingly spawned the nineteenth-century myth of Celtic origins in Iron Age Central Europe.

This alternative view led me to search for any other classical references which might give more specific or consistent early geographical locations for the Celts. Since Herodotus may have been deliberately misread, I needed to take the same legalistic approach to any original source. In this way, it might be possible to tease out a more consistent and specific picture.

During classical times, the Celts had a particular aversion to putting anything about themselves in writing. This frustrating quirk was due not to a lack of literate Celts in the Roman Empire, for they certainly wrote about other things, but apparently to a real disinclination to write about themselves. So over roughly a thousand years from the sixth century

BC

, we find numerous references to ‘Keltoi’ (Greek) and ‘Celtae’ (Latin) by mainly non-Celtic classical authors. This long period of use implies that the term ‘Celt’ was continuously regarded as a useful descriptor, whatever evolutionary changes there were in its meaning.