The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (39 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Figure 6.1a

The early spread of farming from the Near East through Europe. In the past it was thought that Neolithic farmers largely replaced pre-existing Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Europe. Genetic studies ought to help determine the degree of that replacement.

In addition to the dating dilemma, Renfrew saw an important issue in the question of where the huge Indo-European language tree was rooted. Where was its homeland? After all, its branches reached from Ireland in the west, north to the Arctic Circle, east to Central Asia and south to Sri Lanka. Large water bodies such as the Mediterranean, the Black Sea and the Caspian, not to mention mountain ranges such as the Caucasus, Taurus and Zagros, limit the possible corridors of travel in the Near East. So the Kurgan nomadic hypothesis would predict a very different language tree from the Anatolian farmer hypothesis. Renfrew acknowledged that there was a degree of controversy over the linguistic evidence, especially the limited information available on dead languages, such as Hittite, in his preferred Anatolian homeland. Support for the Anatolian root has increased since his book appeared.

9

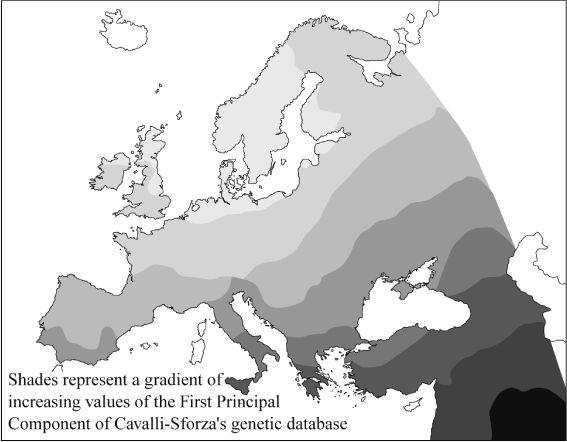

Figure 6.1b

Cavalli-Sforza’s genetic First Principal Component (PC). The similarity between this PC pattern and the spread of farming (

Figure 6.1a

) was previously thought to indicate massive Neolithic gene flow. But there is no date-mark on such PCs, and this image could represent any, or all, movements into the European peninsula from the Near East during the past 45,000 years (each PC gives a composite measure of regional genetic association, in decreasing order of importance from the first PC).

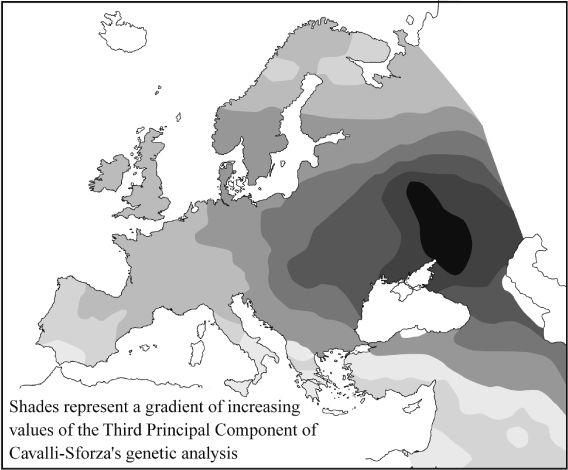

Figure 6.1c

Cavalli-Sforza’s genetic Third Principal Component. This PC appears to show a pattern radiating out from southern Russia, and has been thought to represent the ‘Kurgan invasion’. Again, there is no date-mark, and this pattern may simply signal the post-glacial re-expansion from the Ukrainian refuge – or all gene flow between Eastern and Western Europe.

As genetic support for this view, Renfrew was very impressed with Cavalli-Sforza’s previous mathematical analysis, his ‘wave of advance’, which suggested that although migratory movements of individual farmers of Near Eastern origin might be relatively small, their large families would change the balance of the local population against those of the hunter-gatherers as an advancing wave. In particular this avoided the need to talk about massive migrations, which are now ‘unfashionable’ in the archaeological world. Before going any further, I should point out that Renfrew now takes a rather sceptical view of the meaning of Cavalli-Sforza’s Principal Components Analysis, in particular their lack of dates.

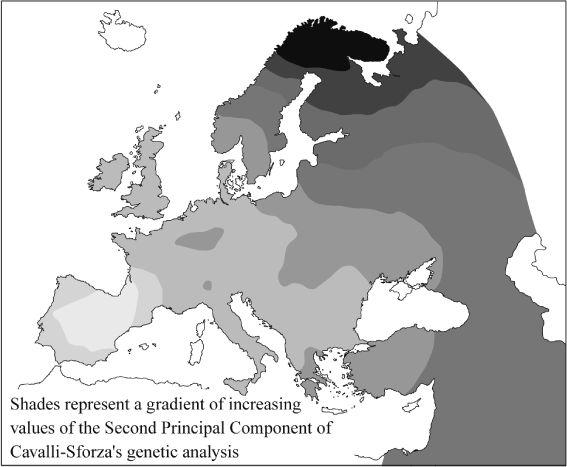

Figure 6.1d

Cavalli-Sforza’s genetic Second Principal Component. This PC appears to show a pattern radiating out from Lapland, for which there is no archaeological counterpart. Recently geneticists have pointed out that PCs do not specify a ‘direction’ of gene flow, and this PC may well represent the post-glacial re-expansion from the Iberian refuge in the other direction.

The trouble with Principal Components Analysis (PCA) is that although it is a good method of displaying genetic distance graphically and separating different genetic gradients and

vectors, it is impossible by this method to date these components as genetic events. So while the Principal Components demonstrate dramatic gradients and obviously represent some migratory phenomena, they could result from multiple migrations at greatly different times along similar trails. Furthermore, although each PCA map shows gradients, the direction of gene flow cannot be automatically inferred from them. Europe is effectively a west-pointing peninsula, so the net vector direction of the First and Third Components is most likely to have been east–westward rather than west–eastward. Not so for Cavalli-Sforza’s Second Principal Component (

Figure 6.1d

), for which the vector stretches from the Basque Country to Lapland. One could not predict from the PCA analysis whether this vector represented the southward Norse invasions of Europe from Roman times onwards or, as is much more likely, that it reflected the earlier and larger northward post-LGM re-expansion from the south-west European refuge (see

Chapter 3

).

Of course, unless one is a modern archaeologist shocked by the past crimes of anthropologists and politicians, there is no particular reason to be coy about using the word ‘migration’ when that is what you mean. After all, migration is what happened after the last Ice Age as people gradually moved to the north and west to fill up the empty spaces. The problem is with inferring migrations largely on the basis of language reconstruction, when language has such a mercurial relationship with the people who speak it. And more important than this is the lack of consensus on the timing of language splits, which gives at best dodgy dates and at worst no safe dates at all.

No one is more aware of the weakness of linguistic dating than Renfrew himself. It is, after all, crucial to his thesis. During his long leadership of the McDonald Institute of Archaeology in Cambridge he organized a number of workshops on issues connected with the Kurgan warrior and farming/language dispersal hypotheses. These have covered a variety of topics, including an examination of when people changed from only eating horses to riding them as well (quite recently, as it turns out). Several workshops have looked at the prehistory of language and attempts to date language splits. Being aware of the potential circularity of dating language from the archaeology, Renfrew would dearly like to see linguists estimate some of their own dates. Linguists who refuse to countenance direct dating are equally convinced that Indo-European cannot be as old as the Neolithic. Curiously, their arguments are based on memories from old theories on the rate of language decay, based on methodology they have long since discarded.

After decades of wilderness years, during which historical linguists have shied away from date estimation and its associated uncertainty, some sort of activity has restarted, with research on language dates published in journals such as

Nature

. However, with the exception of some articles written in Russian, these papers emanate not from linguists themselves, but from a motley assortment of geneticists, psychologists and mathematicians. One might wonder how non-linguists could manage in such an arcane field on their own. Well they do not, quite. The interesting accommodation is that the same old warring linguists provide the linguistic data – the all-important sets of cognates – and, apparently in return, avoid having their names as authors on the papers.

I have already mentioned some of this language-dating research in

Chapter 1

in the context of celtic splits, but the estimates attempted by these researchers also go right back to the roots of Indo-European. As before, I shall discuss the same two groups: Forster and Toth, whose dates and methods are bold and yield old dates, and Gray, Atkinson and colleagues, whose methods are more conventional linguistically and produce younger splits.

Russell Gray, Quentin Atkinson and colleagues have not only used the largest body of data, but also compared two independent datasets and followed a conventional linguistic approach, of sticking to well-attested cognates. Their mathematical approach attempted to reduce a variety of sources of error and bias.

10

They first analysed a set of cognates constructed originally by Isidore Dyen and colleagues.

11

Dyen was both famous and notorious amongst linguists for his previous use of a dating technique called glottochronology (literally, ‘dating sounds’). Although they do not use glottochronology, much of the lexical re-analysis performed by Gray and Atkinson does not actually alter the broad relationships Dyen noted among Indo-European languages, although the latter expressed them graphically in terms of proportions of shared cognates.

In constructing their language tree (

Figure 6.2a

) from Dyen’s dataset, Gray and Atkinson adopted Renfrew’s favoured Anatolian root, although they acknowledge that this could introduce bias:

rooting the tree with Hittite could be claimed to bias the analysis in favour of the Anatolian hypothesis. We thus re-ran the analysis … rooted with Balto-Slavic, Greek and Indo-Iranian … This increased the estimated divergence time from 8,700 years

BP

to 9,600, 9,400 and 10,100 years

BP

, respectively.

12

Using a different Indo-European dataset, provided by linguist Don Ringe of the University of Pennsylvania, Atkinson, Geoff Nichols, David Welch and Russell Gray reconstructed a very similar tree with very slightly younger dates (

Figure 6.2b

).

13

Before discussing those dates, I should like to demonstrate how the European branches

could

be structurally interpreted as fitting the big, archaeo-genetic Neolithic arrows explored in previous chapters that point to farmers moving west and north out of Anatolia and the Balkans. I keep an open mind, however, as to the real significance of these interpretations. The first thing to note from both trees is that the eastern Mediterranean Indo-European languages such as Greek (and probably Albanian) and Armenian split off early, apparently before the Indo-Iranian branch headed off down south-east to South Asia. Earliest of all are the Anatolian languages spoken by Hittites and Lycians, whose sophisticated civilizations anticipated Greek and Cretan cultures. We can also note that Greece and Turkey are noticeably lower in their frequency of the European Y gene group Ian (I) than the Balkan countries immediately to their north.

14

In Dyen’s original analysis, three of the remaining four European-based Indo-European language branches (Romance, Germanic, celtic and Balto-Slavic) belonged to a super-branch which, with the interesting exception of celtic, he called

Meso-Europeic

. Populations speaking Meso-Europeic languages all have higher rates of European Y gene group Ian, thus setting them apart from the insular-celtic speakers (and Greeks). In Gray and Atkinson’s re-analysis of Dyen’s data, however, the deepest split in the Meso-Europeic branch yields the ‘Balto-Slavic’ group rather than celtic. Balto-Slavic covers the whole of Eastern Europe with the exception of Rumania’s and Hungary’s recent linguistic intrusions. This branch includes the eastern Baltic languages Lithuanian and Latvian, and the huge Slavic group stretching from Bulgaria and the Balkans in the south to Poland and the Czech Republic in the west and Russia in the east. The most obvious Y-chromosome branch that describes this Balto-Slavic distribution best is Rostov (R1a1). The other grouping is I1b*,

15

which I described in the previous chapter as probably moving north and east out of the Balkans, and fits the Balto-Slavic spread as well, except that it does not feature strongly in Poland or in the eastern Baltic states.