The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (37 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

The Bronze Age saw a dramatic increase in trade between the British Isles and Europe, at least to the extent that the archaeological visibility can tell us. In

Chapter 2

, I discussed the tin trade, which covered all the stations on the Atlantic coastal trade network and gave the western British Isles a unique importance to the Mediterranean. There was, however, a progressive overlap between the Atlantic trading zone and the north-west European one, with centres along the major rivers such as the Rhine, Seine, Loire and Thames joining in the network. As with the Neolithic, this overlap was seen particularly along the south coast of England. Here it centred on the Wessex Bronze Age elite cultures, in the same region as Stonehenge, which may have acted as a common market between eastern and western influences. Zones manufacturing prestige goods developed in small regions along the Atlantic fringe; they later specialized and became part of a trade network linking north-west with southwest Europe.

140

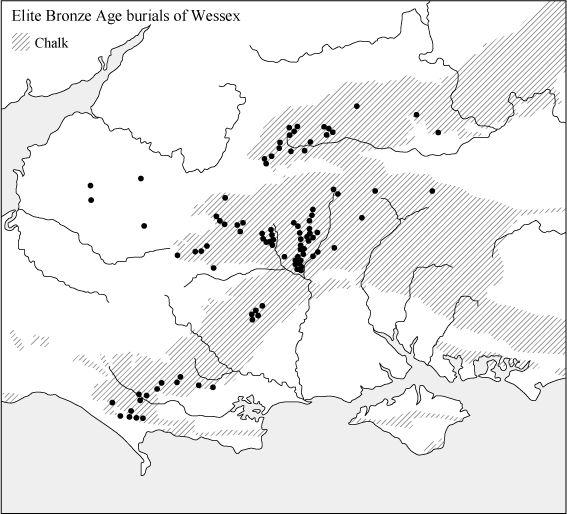

Figure 5.13

Distribution of elite Bronze Age burials in Wessex.

Wessex, already the ritual centre of England during the Neolithic, continued its dominance during the Bronze Age, between 4,000 and 3,400 years ago, with lavish, rich individual burials replacing communal graves (

Figure 5.13

). The fact that these were in the same locations as the earlier Neolithic monuments is cultural evidence for the continuity of an indigenous population taking on new fashions rather than being replaced by invasion and this is consistent with the quiet genetic picture.

141

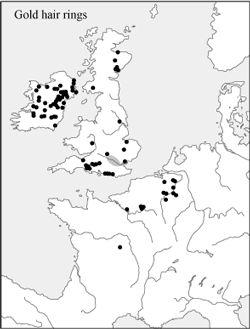

Between 4,000 and 3,500 years ago, precious metals joined the Neolithic trade routes, with items such as gold lunulae (ornaments in the shape of a crescent moon) moving from Ireland to Cornwall and Brittany. Bronze Age gold hair rings made in Ireland later in the Bronze Age, around 3,000 years ago, appear to have been trans-shipped in Wessex on their way to destinations on the Rhine (

Figure 5.14a

).

142

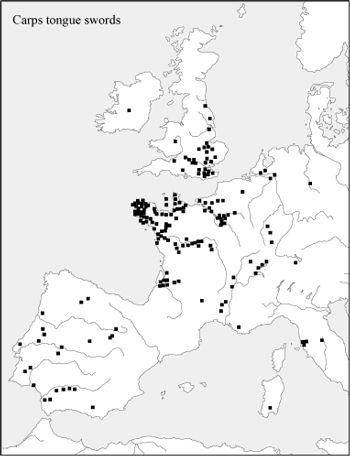

Around the same time, but in the reverse direction, so-called carp’s tongue swords (

Figure 5.14d

), a long bronze sword with a slotted hilt, originating in Brittany, started to appear along the Atlantic coastal fringe, penetrating up major rivers from western Germany to western Iberia. They were also common in England, but here, breaking with the western tradition associated with the Atlantic tin trade, they are found concentrated in the east and south-east of the country and quite far up the Thames.

143

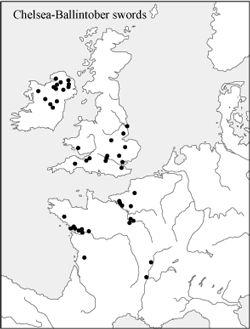

Another bronze sword, the Ballintober type, traded out from Ireland to south-east Britain and to the Seine and Loire Valleys 3,100 years ago (

Figure 5.14b

).

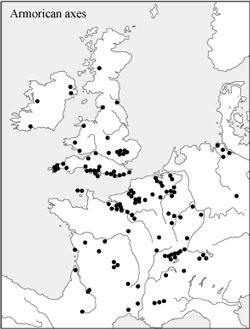

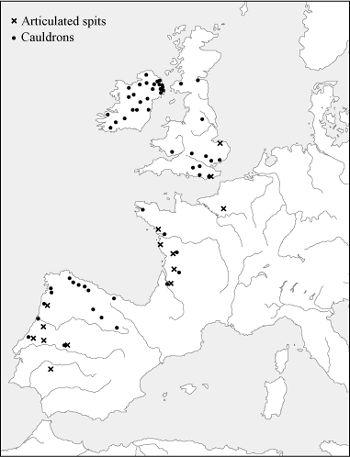

Bronze Age barbecues with elaborate articulated roasting spits and cauldrons became quite the thing along the Atlantic coast from 3,000 years ago (Plates 12 and 13). The distribution of these beautiful objects includes not only western Iberia, north-west France and Ireland, but also south-east England and the Thames (Figure 5.13e). Slightly later, 2,700 years ago, Armorican (i.e. Brittany and Normandy) socketed bronze axes did similar rounds, spreading from the south of France to the River Elbe in northern Germany. Although they were widespread in the British Isles, hoards of these axes, almost like deposit banks, concentrated along the south coast (

Figure 5.14c

).

5.14a–e

During the Bronze Age, prestige items were traded from the British Isles across the English Channel and North Sea, both ways, in a variety of networks, usually including Wessex.

Figure 5.14a

Thick, slotted gold hair rings were made in Ireland in the Late Bronze Age. They were traded via Wessex to nearby northern Europe.

Figure 5.14b

Chelsea-Ballintober swords. Swords of the Ballintober type were made in Ireland around 3,200 years ago and found their way to south-east England and the Seine and Loire valleys in France.

Figure 5.14c

Armorican socketed axes. Tens of thousands of these were made in Brittany and Lower Normandy. Most were buried in hoards locally, but some were exported throughout France and to southern Britain, particularly the south coast.

Figure 5.14d

Carp’s tongue swords were long with a narrow point and slotted hilt; made in western France, they are found in eastern England and along the Atlantic seaways.

Figure 5.14e

Elaborate barbecue spits and small bronze bowls, used for elite feasts, were introduced into Iberia around 3,000 years ago and spread along the Atlantic coast to eastern Britain and Ireland.

Between 2,700 and 2,500 years ago, the balance of the two networks connecting the British Isles to the Continent tipped towards the east. Britain, and to a lesser extent Ireland, was now linked predominantly with powerful chiefdoms in Northern Europe. Chieftains in eastern England may have been receiving gifts of horses and four-wheeled vehicles, not to mention swords, and even learning the dwarvish craft of iron-working.

144

The Rhine connection with Britain developed in the Late Bronze Age. In return for the Ballintober sword, west Central Europe created the Hemigkofen sword type, which found its way down the Rhine and across to East Anglia and the Thames Valley. Later, from 2,700 years ago, the bronze Grundlingen sword of the Hallstatt C warrior aristocracy became popular in eastern Britain, especially the Thames Valley. Copies may even have been made locally. This weapon also appeared in Ireland, although without the horses with which it was associated in Britain. It is possible that Irish gold flowed in the opposite direction, but there is no evidence of east–west people flow, either to or from Ireland.

145

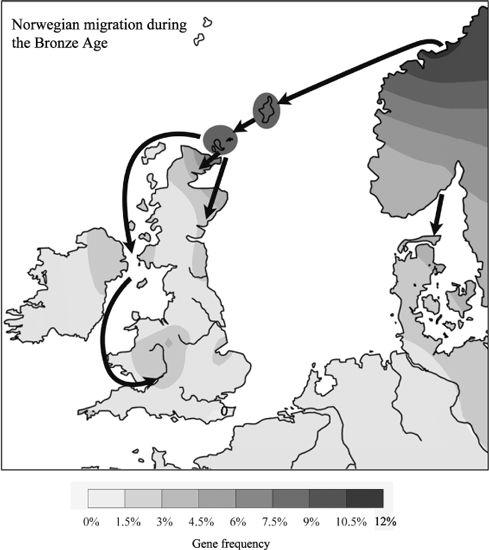

Are there any genetic parallels for the intensive Bronze Age interchange between Europe and the British Isles? Yes there are modest ones, but the gene flow intensifies the North Sea links and is nearly exclusively from north-west Europe, including Scandinavia, to the east coast of Britain up to Orkney and Shetland, and even down to the Channel Islands. Wessex in spite of its central position in trade, does not feature at all in this gene flow. Again, the two main north-west European gene groups, Ian and Rostov, contribute the clearest evidence in the form of two dated clusters each. This was by no means a dramatic migration, contributing in all only 3% to the British gene pool.

146

The two relevant Ian clusters date to around 4,000 years ago (

Figures 5.15a

and b), and characterize respectively East Anglia and north-east Britain, including Orkney and Shetland.

147

On the Continent, the former derives from northern Germany, the latter from Norway. The two related Rostov clusters date to 3,700 and 4,100 years ago, and derive respectively from northern Germany and Norway. The former is found all along the east coast of England, while the latter targets the islands off the north of Scotland.

148

5.15a–b

In spite of the evidence for massive trade links, little Bronze Age gene flow can be detected from Europe into the British Isles – all of it from Scandinavia and north Germany.