The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (36 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

In this chapter I have presented evidence for large-scale Neolithic gene flow from the Balkans/Ukraine area into northwest Europe marked particularly by the Ian male group. Ian is also represented in the Ukraine and farther east in the so-called Kurgan homeland, north of the Caspian Sea.

124

From the Late Neolithic in north-west Europe they are in fact coincident, so we cannot exclude the regions and dates (6,000–5,000 years ago) proposed for the source of the Corded Ware/Battle Axe cultural traits.

In addition there is the question of male gene group R1a1 (Rostov), which more convincingly characterizes the Balkans, Eastern Europe (in particular Poland)

125

and the steppe region. Zoë Rosser and colleagues at the University of Leicester proposed Rostov as the Kurgan marker.

126

In my analysis, Rostov has at least four clusters with different dates for expansion in north-west Europe, so they cannot all be ‘Kurgan’. One of these, R1a1-2, moved down into northern Scandinavia in the Middle Neolithic around 5,700 years ago, appearing in small numbers in north-east Britain, particularly in Shetland and Orkney, around the same time, in other words contemporary with the earliest Neolithic in Shetland (

Figure 5.7a

).

127

This would have been rather earlier than Maria Gimbutas suggested for ‘Kurgan’ culture arriving in north-west Europe or eastern England,

128

and in any case Norway was not involved in the Corded Ware/Battle Axe phenomenon, and the ultimate source of this particular Rostov gene flow would have been Mesolithic folk from Lapland.

R1a1-3, another cluster with a marginally better location and date claim as a ‘Kurgan’ founder originated as a founding event in southern Norway, but is also found in northern Germany and Denmark and eastern Britain and Orkney at modest rates. This later cluster has two sub-clusters dating in Britain to between the Late Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age, around 4,000 years ago (

Figures 5.15a

and

5.15b

).

129

Southern Scandinavia did share in the distribution of the corded-ware culture and traded copper with the Balkans. A little later during the Bronze Age, Baltic amber was traded along the same routes (used to trade tin from Britain and copper from the Baltic).

130

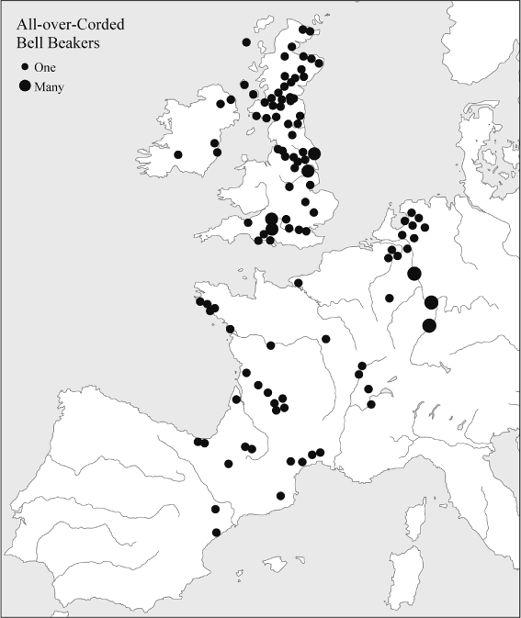

What has all this to do with Britain, which did not have its own Corded Ware/Battle Axe culture? Britain may not have consistently had the full cultural package, including the original battleaxes and corded ware beakers with stepped feet, but there are lots of individual beaker burials, particularly along the east and south coasts, characterized by a type of beaker known as All-over-Corded (AOC) Beaker, which developed in the Netherlands around 4,700 years ago.

131

These beakers, decorated all over as their name suggests with cord impressions, are found commonly in the Rhine Valley, the Netherlands and Britain (

Figure 5.12a

). The predominantly east and south coastal distribution seems yet again to emphasize the geographical relationships of these regions of Scotland and England to the nearby Continent,

132

as suggested by the distribution of both the Rostov and Ian Neolithic intrusive male gene lines there.

5.12a–b

The Beaker phenomenon and the British Isles.

Figure 5.12a

All-over-Corded Beakers were developed in the Netherlands and spread throughout France and distributed more to the eastern side of the British Isles.

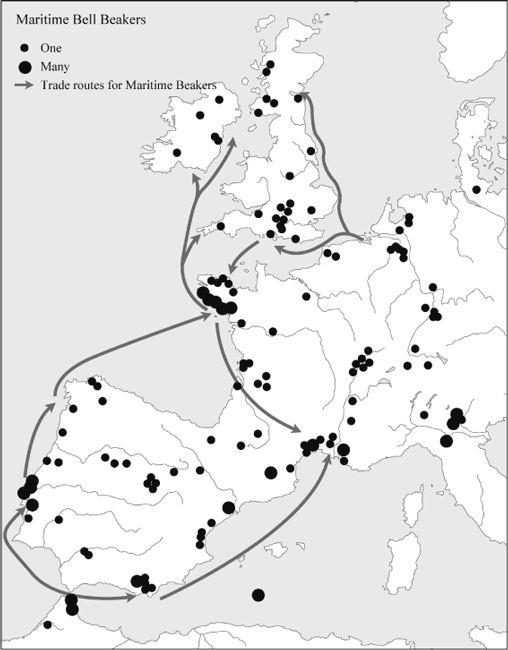

Figure 5.12b

Maritime Bell Beakers: the style evolved in Portugal and spread by maritime trade along the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts (arrows) and also to the western rather than eastern British Isles (arrows include exchange networks across the English Channel for All-over-Corded Beakers as well).

If there should be any doubt about the genetic evidence for Continental influence and movement of people into England between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago, we have some extraordinary direct non-genetic evidence in the form of a recently excavated set of grand beaker burials about 3 km from Stonehenge and a similar distance from the great temples of Woodhenge and Durrington Walls. In the general media excitement, the highest-status burial was dubbed variously the ‘Amesbury Archer’ and ‘King of Stonehenge’ (Plate 8). The latter appellation partly derived from the location and the fact that Stonehenge went through one of its main stone facelifts around that time.

Six other bodies subsequently turned up during excavation, including one which, bone analysis suggests, could have been a male relative of the Archer. Grave goods included eight beakers, seven of which were decorated all over (AOC), six with cord, one with plaited cord. Other typical beaker grave goods included a black sandstone wrist-guard (on the archer’s forearm), a bone pin (which may have held a cloak), several copper knives, boars’ tusks, a cache of flints, a shale belt ring, two gold ‘earrings’, and tools including an antler spatula for working flints. The radiocarbon dates show that the Archer lived between 4,400 and 4,200 years ago.

133

Stripped of all the media hype and the rich artefacts, the most interesting aspects of this high-status interment were that it is a typical Continental beaker burial, close to and contemporary with the greatest henge monument of all. And, most surprisingly, there is evidence that the Archer was not local at all,

but from elsewhere in north-west Europe. The enamel on our teeth stores a chemical record of the environment where we have grown up. Scientists use a technique called oxygen isotope analysis to measure this record. The Archer’s teeth show that as a child he lived in a colder climate than that of Britain today, in Central Europe, and possibly close to the Alps.

134

It may be that there was too much desire among archaeologists to place him in Switzerland and the Alps, but the isotopic study shown as a contour map (similar to the genetic maps in this book) gives a band of possible locations with similar isotopic records, stretching from the Alps, north-east through Poland, to Finland. Chemical analysis of his knife shows that the copper came from Spain.

Clearly, one dead rich archer and six relatives do not an elite migration make, but they do anything but rule it out. The status and geographical location of this individual, at origin and death, hints at an elite network of power stretching well beyond the North Sea rim and is consistent with the male genetic evidence for Neolithic migration that I have discussed.

Cunliffe traces a different distribution and history for another type of beaker, called the Maritime Bell Beaker (

Figure 5.12b

). As mentioned above and in the previous chapter, he sees these as markers for an Atlantic façade trade and culture network through which metal-mining and possibly celtic languages were introduced to the British Atlantic fringe from 4,400 years ago. He argues that the Maritime Bell Beaker form evolved in Portugal, rather than the Netherlands, from about 2,800

BC

.

135

So although the original genesis of Bell Beakers, as a general pottery type, was in north-west Europe, they evolved in the different parts of the west and eventually entered Britain as

two broad types, reinforcing the now long-standing west/east division. Whether celtic languages arrived at this time or were already established as a trade network language in the earliest megalithic phase is a matter of speculation. I prefer the latter view.

Both these routes of entry of beakers to the British Isles had some connection with the use of copper. For the Atlantic coast there was the attraction of the copper mines in Ireland and Wales, while for the east coast there was no local copper and prestige items had to be traded probably from the Balkans, where the copper age had started long before, during the Early Neolithic.

There was considerable cultural overlap between the Neolithic and the Metal Ages. At the point of leaving the Neolithic and moving on to mix newer metals with Neolithic copper, I would like to mention one of the sample locations for the Y-chromosome analyses, the one that showed the closest genetic resemblance to a Late Neolithic Spanish colony, although the archaeology points to the British Early Bronze Age. This is the small town of Abergele, already mentioned as the British location with the highest Neolithic genetic input, on the north coast of Wales, situated near Llandudno. Until the nineteenth century, the nearby rocky promontory of Great Ormes Head had working copper mines. Recent archaeological excavations at Ormes Head reveal evidence of copper-working going back more or less continuously to the Early Bronze Age, 3,700 years

ago. Pottery is notably absent from the mine workings, but is present in ‘Kendrick’s Cave’, situated on the east-facing cliffs of the Great Orme overlooking Llandudno town, where shards of Beaker pottery and Peterborough Ware have been found.

136

Abergele stands out in all the genetic distance maps in my analysis since it always stands away from the rest of the British samples, being better matched to Iberian sets. The first reason for this is that it holds a high proportion and diversity of Balkan/Iberian Neolithic lines, such as E3b (

Figure 5.8a

), which makes up 33% of the total. Furthermore, the selection of Ruisko lines (56% of the total) is more typical of two Spanish metal-rich regions of Valencia and Galicia (and to a lesser extent Catalonia) than of the Basque Country types. Just to demonstrate its diversity and lack of drift, Abergele also has 11% of the North European Neolithic Ian gene group.

137

The point of mentioning this unique genetic connection between the Neolithic and Bronze Age here is that this evidence of skilled metalworkers arriving from Spain supports the ample archaeological evidence of metal trade and bears out Barry Cunliffe’s prediction of the

Longue Durée

– long-term continuity of the Atlantic coastal trade network.

Apart from this tantalizing gem of Welsh mining prehistory, there is no other specific or convincing genetic evidence for Bronze Age or Iron Age gene flow into the British Isles from Iberia. This of course does not mean there was none, just that the genetic evidence indicates that the majority of male and female lineages for which dates can be ascertained arrived in the British Isles before the Bronze Age.

138

I have looked for evidence of such a link with Spain on Principal Components Analysis (for a description of this method

of measuring genetic distance, see

Chapter 11

) in other metal-rich areas of the western British Isles, but although Llangefni in north Wales shows some similarity, there are no sample locations from southern Ireland, and Cornwall shows only a small trend, rather less in fact than in south-coast genetic sample locations such as Dorchester in Dorset, near the Bronze Age ritual centres of Wessex (

Figure 5.4

). In fact, the south-coast centres still show a slightly greater male Late Neolithic genetic input from north-west Europe than from Iberia (

Figure 5.7b

), but none from either source specifically during the Bronze Age. The 3% Bronze Age input to the British Isles from Northern Europe distributed further north and east (

Figure 5.15

).

139