The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (16 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Celts were real rather than mythological people to the Roman and Greek authors for over a thousand years. Ancient literary evidence points to their early presence in Spain, southern France and Italy, thus contradicting the nineteenth-century view of their origins in southern Germany. Inscriptional evidence indicates that languages closely related to insular celtic are found in the same southern distribution over the same period, and were the main vernacular alternative to Latin there. Given this distribution, Caesar’s remark that people in central Gaul, south of the Seine and Marne rivers and west of the Garonne, referred to themselves as both Celts and celtic-speaking is consistent with Buchanan’s and Lhuyd’s view that there was a close link between insular celtic and the classical Continental Celts. This contradicts the Celto-sceptic view that the term ‘Celtic’ is based on a worthless myth best left, with its fuzzy linguistic associations, in the classical period.

There is good direct and circumstantial evidence that insular celtic was present in most parts of the British Isles at the time of the Roman invasion, although not as abundant in the one place where there should be the most evidence – England. Controversial linguistic-dating evidence may link the spread of celtic languages, not with the spread of Central European Iron Age Hallstatt and La Tène cultures as presently held in

the orthodox view, but from a different region in earlier times stretching from the Bronze Age possibly back to the Neolithic.

OLONIZATION OF THE

B

RITISH

I

SLES BEFORE THE

R

OMAN INVASION

AN LANGUAGE DATING TELL US WHEN THE

C

ELTS ARRIVED

?

In the last chapter we saw that any reappraisal of the scattered comments of classical historians and evidence from non-Latin inscriptions tends to challenge the nineteenth-century theory that the Celts emerged from southern Germany during the Iron Age and spilt out over Europe, invading the British Isles only a couple of hundred years before Caesar. Rather, those texts and the locations of ancient celtic inscriptions seem to point towards an earlier, south-west European linguistic origin for the celtic languages that now survive only in Brittany, Ireland, Wales, Cornwall and Scotland. This alternative south–north language arrow resonates with archaeologist Barry Cunliffe’s

description of an Atlantic coastal culture spreading up the coast from the direction of Spain during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, and agrees with many accounts of Irish legends and traditional history. This perspective is clearly neither the whole story nor a secure revision of Celtic cultural origins; and the devil is in the dates.

At the more recent end of the language scale we have celtic linguists who would rather not commit themselves on the history of celtic languages any further back than the texts, inscriptions on stone and bronze, can take them – that is, not much earlier than the Christian era.

1

A little further back in time, we have other linguists disputing how deep the relative structural split is between the Gaelic and Brythonic celtic branches, but still unwilling to commit themselves to any absolute timescale.

When we do get dates, they are emphatically not supplied (nor generally endorsed) by linguists, but by people experienced in drawing genetic trees. Nonetheless, respectable linguistics has been used to construct those trees and their derived dates. Two different research groups recently produced results for the Indo-European family, although they systematically differed in dates of splits by over 2,000 years.

As mentioned in the last chapter, mathematicians from the University of Auckland compared two different tree-building methods on sets of data they obtained from two linguists working independently. The two datasets yielded similar overall estimates for the break-up of celtic into Irish and British branches: one 2,500 and the other 2,900 years ago.

2

Peter Forster of Cambridge University and Alfred Toth of Zurich University used a rather different, so-called

network method

derived from genetic studies and estimated 5,200 years for the

of Gaulish, Goidelic and Brythonic from their most recent common ancestor.

3

Now, all of these dates will have their own inherent errors, but the implication is that we are looking at separate celtic-language and British-culture stories starting from at least the time of the Bronze Age, if not earlier – in any case, before the Iron Age. The earliest evidence for metal mining in the British Isles comes from southern Ireland and north Wales, connecting up to the pre-existing metal industries of Brittany and the Spanish Peninsula. This finds cultural resonance in Cunliffe’s description of the simultaneous introduction of the Maritime Bell Beaker – a pottery style from the same Atlantic regions (

Figure 5.12b

).

However, when we look further, at equivalent estimates for the separation of celtic languages as a whole from other Indo-European languages, a much deeper timescale appears. Dates for the separation of the ancestor of celtic languages from Italic and Germanic language roots are estimated at around 6,000 years ago by the Auckland group.

4

In other words, celtic-linguistic roots could go well back into the Neolithic period.

The Neolithic, or the New Stone Age, was also the time of the spread of agriculture into Europe, and Colin Renfrew has argued strongly that Indo-European languages spread throughout Europe on the back of agriculture. If the celtic Indo-European branch had a Neolithic date of separation, the implications for its influence on European prehistory take on a quite different perspective from that of the spread of a successful Iron Age tribe.

Before opening Pandora’s box and plunging back into speculative cultural, linguistic and even genetic links along the Atlantic seaboard drifting ever further back into an opaque celtic-linguistic prehistory, I would like to address the genetics primarily in this section and put the peoples of the European Atlantic coast in a broader time perspective. Whether celtic languages were introduced to the British Isles during the Neolithic or the Bronze or the Iron Age, those who introduced them were not the first people in Britain, and in common with Anglo-Saxons, Vikings and Normans, need not

necessarily

have made much numerical impact.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was a tendency to equate culture, language and people. This usually meant combining the three together with genetic heritage into a ‘racial’ package, and seeing all three as moving in concerted historical and prehistoric migrations. The idea of large-scale gene flow is still with us, encapsulated in the racial use of the word ‘blood’. So, for instance, we find a documentary title such as ‘Blood of the Vikings’, intended to imply that we could simply look for Viking genes and work out how much ‘Viking blood’ made its way into the British Isles, and where. While I am interested in looking for specific gene flow, I do think that it is important to get away from the idea that genes, language and culture move together in equivalent doses. France has since Roman times spoken a Romance rather than a celtic language, but this is not to say that the bulk of French ancestors physically came from Italy. This is a typical example of the phenomenon of ‘language shift’ following invasion. The impact of a new

movement of genes into an old population depends far more on the size of the pre-existing gene pool than on any archaeologically visible cultural changes. One of the good things about the politically correct archaeological reaction to racial migrationism in the late twentieth century is that it has forced upon us the realization that culture and language can move relatively independently of gene flow; but that does not of course mean that they always do.

While it is clear that different parts of Britain do show clear genetic differences, these differences do not necessarily relate to any ethnic labels we might think of, which are mostly only a couple of thousand years old. So I shall move away from language issues to give some geographic, climatic and genetic perspectives to the recurrent patterns of colonization of the British Isles since the last Ice Age, around 15,000 years ago. The reason for this is not just a check against moving to overenthusiastic conclusions that all ‘Celts’ came over to the British Isles during the Bronze Age or whenever, but a change in focus towards the main migratory issues which form the core of this book. As we shall see, there is abundant genetic evidence linking Spain with Ireland and Wales by multiple migrations. But even such parallel links do not automatically give a date, size or number for ‘Celtic migrations’. Genes are a proxy for actual migrations, while language only may be. Language is, more importantly, a proxy for cultural movement. And what if there were similar recurrent migrations up the Atlantic coast before and after the Bronze Age? As it turns out there probably were – both.

FTER THE ICE

The theme of this book is that the British Isles were colonized from two different parts of Western Europe. These two geographic origin-trails, being reinforced by geography and recurrent long-term contact, could have persisted independently creating routes of cultural and genetic affiliation throughout prehistory. These would have continued through the historical period until the present day. This chapter is as much about climate and geography as it is about the main core of the book – people. But the former guided the latter in their movements. The initial colonization of the British Isles, after the ice melted, also set the scene and patterning of the later genetic landscape.

Europe, although previously inhabited by Neanderthals and their human forebears, has only been occupied by our kind,

Homo

sapiens

, for perhaps 50,000 years,

1

with a considerable amount of internal mixing over those millennia. So why should we even consider it possible to get more than the vaguest story of the peopling of one corner of this long continent? It is possible, and for that we can thank the climate.

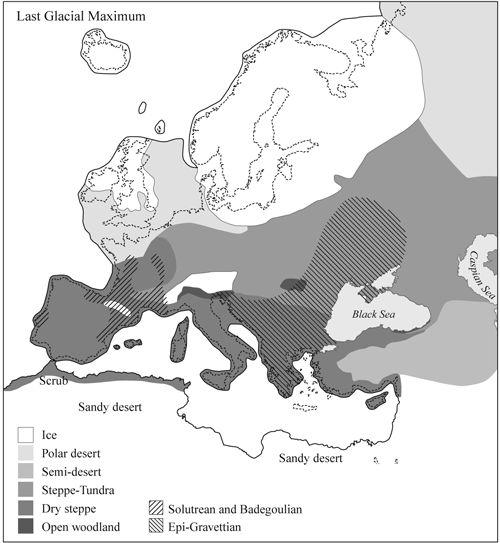

During glaciations, the sea level falls by as much as 127 metres as a result of water being locked up in the huge ice caps. At the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) – the peak of the last Ice Age, between 22,000 and 17,000 years ago – the North Sea and the English Channel dried up, and Britain was joined with Ireland and France as part of the larger European landmass. It is almost certain that this British corner of Greater Europe was completely cleared of people at some time during the LGM. Not only was a large part of the British Isles actually covered by a thick layer of ice, like Scandinavia in the north-east, but those parts of the British extension of the Continent, south of the ice, were uninhabitable polar desert (

Figure 3.1

). This means that whoever had lived there before the ice had now gone, leaving an empty landscape and only their bones and tools – and a blank genetic sheet (

Figure 3.1

). So we can be sure that the colonization of Britain began afresh after the LGM.

The same bleak picture applied to much of north-west Europe. Scandinavia, the Baltic Sea and coast, and Finland were covered in ice, with sterile surrounding zones of polar desert. The neighbouring north-east European regions of Murmansk, Karelia and Archangel were polar desert, as were the coastal zones of northern Germany, Frisia, the Netherlands, Belgium and northern France down as far as Brittany (

Figure 3.1

).

In this chapter, I ask how soon the first permanent recolonization of Britain followed the LGM, and what contribution those settlers made as ancestors for today’s populations. I ask ‘how soon’ and specify ‘permanent’ recolonization, as there was a short, severe glaciation, the Younger Dryas Event, several thousand years after Europe’s main post-LGM deglaciation. It is suggested, but unproven archaeologically, that some early entrants after the LGM survived the Younger Dryas in the British Isles, forming a permanent nucleus. I aim to show that they did, that those first settlers in the short window of opportunity after the LGM known, confusingly, as the

Late Glacial

(coinciding with a European cultural period called the

Late Upper Palaeolithic

–

Figure 4.1

), contributed a substantial proportion of ancestors to our modern fathers and mothers. Having argued for the sterility of much of north-west Europe in the last Ice Age, I should add that the rest of Northern Europe was not unoccupied. In Eastern Europe, thriving communities extended up the tributaries of the rivers Don, Dnestr and Dnepr in the Ukraine and in Moldavia, both north of the Black Sea. Here, the expert mammoth-hunters had adapted well to the treeless Arctic landscape that now covered most of Central and Eastern Europe south of the ice. This landscape, known as steppe tundra, is similar to parts of northern Siberia today. Farther west, although the steppe tundra extended into southern parts of Germany, there is little evidence (just two sites in southern Germany

2

) for such hardy human activity north of the Alps at the LGM.