The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (19 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

One reason for trying to resolve the Helina tree better is that it makes it much more personal and specific if we can show when, and from where, more than half our British maternal ancestors arrived. For a historian of migrations, measuring the size of the older migrations is useful in estimating what is left over for the more recent invasions. As to who and what were the main British ancestors, we can say they were largely Ice Age hunting families from Spain, Portugal and the south of France. The Basque region still preserves the closest genetic image of the Ice Age refuge community. Obviously, the Basque refuge area has since received intrusions of its own, particularly from the Mediterranean and North Africa, but these

still constitute only a small percentage of that region’s present-day gene pool.

Can the Y chromosome, which is carried only by men, tell us a similar, different or better-resolved story? The answer is very similar, although as usual the geographic patterning is far better resolved and more informative than the female picture.

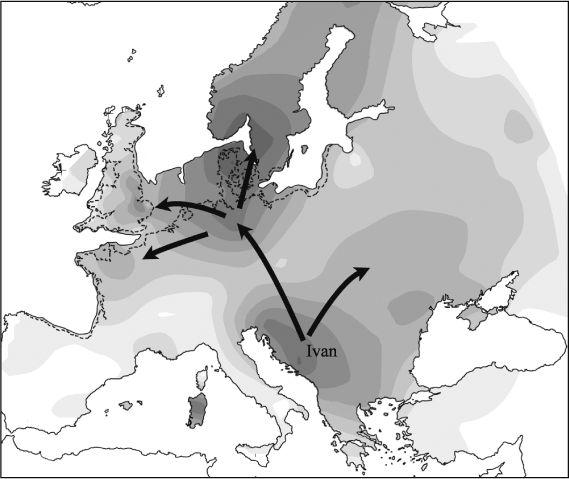

The large Y gene group R (nicknamed

Ruslan

) is the closest male equivalent of the maternal Helina group, accounting for ancestors of half of Europe’s men; he moved into Central from Eastern Europe 30,000 years ago and thence to south-west Europe before the LGM.

33

As a result, presumably, of genetic drift, only one discrete R gene group emerged from the western refuge after the LGM – this is the sub-group labelled R1b.

34

In the Basque Country, R1b achieves his highest frequency at around 90% of the male population, confirming his claim to be the main, and probably the

only surviving

, south-west European gene group as a result of severe genetic drift during the Ice Age. The

overall

R1b gene group I shall refer to as

Ruisko

. This is a Basque male name, chosen for its coincidental similarity to

Russkiye

(‘Russian’) and intended to imply an ultimate pre-glacial origin with Ruslan as ancestors in Eastern Europe.

35

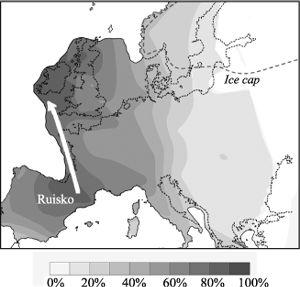

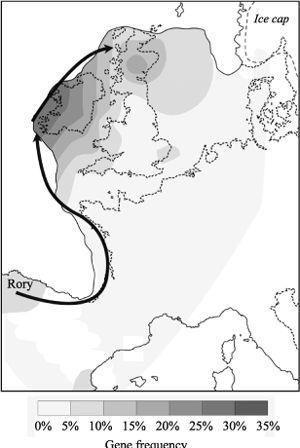

Ruisko’s frequency declines the farther north and east along the mainland European coast one goes, from 90% in Basques, 70% in the Dutch, 60% in the French and 50% in Germans, to 36% in Danes, around 25% in Norwegians and Swedes, 21% in northern Russians, and 18%, 16%, 7% and 0%, respectively, in Estonians, Poles, Latvians and Finns around the Baltic coast (

Figure 3.6a

).

36

The sharp fall-off in frequency of Ruisko going across the mouth of the Baltic to Sweden and thence east to Russia ties in with an early recolonization of mainland north-west Europe from the south-west, while the bulk of Scandinavia was still covered in ice. However, even the 25% rates in the far north, in north-west Scandinavia, indicate the ultimate geographical extent of spread from the Spanish refuge.

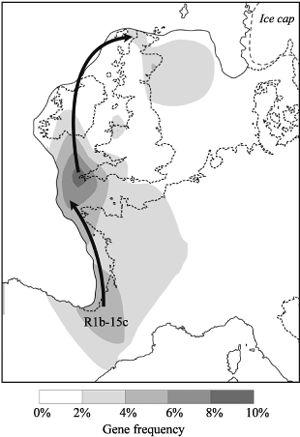

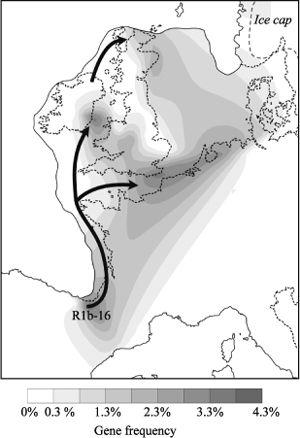

3.6a–f

Male re-expansions into north-west Europe from Iberia immediately after the Ice Age. Contour maps of gene frequency – arrows indicate direction of gene flow based on the gene tree and geography. Contours follow greater land area resulting from low sea level.

Figure 3.6a

Ruisko gene group (R1b). This map shows the impact of all male re-expansions from the south-west European refuge; Ruisko (R1b) represents nearly the entire source gene pool from there. The densest gene flow follows the Atlantic façade, thus favouring Ireland. Since Ruisko also covers later periods, contours are shown in Scandinavia beyond the ice line.

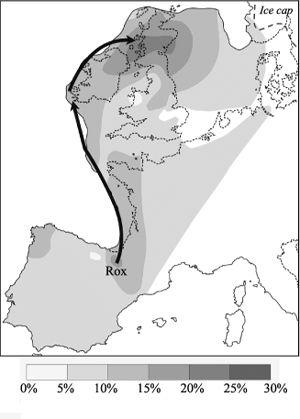

Figure 3.6b

Rox gene cluster (R1b-9). This map shows the impact of the earliest male re-expansion from the south-west European refuge, 15,000–13,000 years ago; Rox is the main source gene cluster for that period. The gene flow follows the ancient extended coastline, favouring Ireland and Scotland.

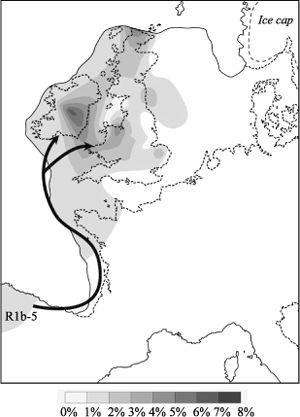

Figure 3.6c

R1b-5 gene cluster. This map shows another of the earliest male re-expansions from the south-west European refuge 15,000–13,000 years ago. R1b-5 derives from Rox and also concentrates on the Atlantic façade, featuring in Ireland, Wales and northern Scotland.

Figure 3.6d

Rory gene cluster (R1b-14). This map shows Rory, one of the larger early male clusters to re-expand from the south-west European refuge 15,000–13,000 years ago. Rory derives from Rox, also concentrating on the Atlantic façade, featuring particularly in Ireland and less so in Scotland. He is strongly associated with Irish men with Gaelic names – but this does not mean that Gaelic arrived so early!

Figure 3.6e

R1b-15c gene cluster. This map shows R1b-15c, another sub-cluster of Rox which re-expanded from the south-west European refuge 15,000–13,000 years ago and concentrates on the Atlantic façade, featuring in this instance in Cornwall.

Figure 3.6f

R1b-16 gene cluster: this map shows R1b-16 another early male re-expansion from the south-west European refuge (15,000–13,000 years ago) that derives from Rox and also concentrates on the Atlantic façade, featuring in Ireland and Wales. Unlike the others, this cluster also moved up the region of the English Channel along the ancient river valley of the Seine to Kent and the Continental Low Countries.

In north-west Europe, Ruisko is replaced partly by R1a1,

37

a distantly related pre-glacial R1 gene group coming from Eastern Europe, the Balkans and ultimately Asia. Not only is R1a1 a minority lineage, but it appears to have arrived in the west via Scandinavia and Poland well after the Younger Dryas.

38

I call him

Rostov

, after cities in the Ukraine and Russia where some of the highest rates are found (not forgetting to mention Tolstoy’s famous character of the same name). There is also another exclusively European gene group, I, deriving from the Balkans and found at high rates in Scandinavia and northern Germany

39

(30–40%, for map of total I distribution see

Figure 3.7

). His Balkan origin earns him the pan-Slavic name

Ivan

. Rostov and Ivan are nearly absent from the Iberian refuge, thus making it easier to measure discrete north-eastern and south-western sources of gene flow in Western Europe and the British Isles, an approach I use throughout this book. I shall come back shortly to these interesting eastern refuge lines, which are important after the Younger Dryas freeze-up.

Just comparing the relative frequency of the Ruisko gene group in different countries to determine their relatedness is a crude and somewhat circular approach since it simply lumps together all members of the same group (Ruisko) that dominates Western Europe and fails to give any perspective in time or space. Unfortunately, the eleven or so clearly defined gene groups (such as Ruisko, Rostov and Ivan) which feature in published West European datasets have yet to have their finer branch structure resolved.

40

From my perspective, this is a problem in particular for the Ruisko gene group, but also more generally for all the other main Y gene groups represented in the British Isles.