The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (21 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

As I have shown, while Rox dominated the early post-LGM scene, and ultimately spread throughout the whole of the British Isles, there is a strong bias in his relative frequency towards the greater Atlantic coastal region and away from England, and particularly

from regions in the south-east such as the south coast and Norfolk. This bias relates to their initial accessibility to beachcombers at that time, since the coastline still extended hundreds of miles out and they were way inland; but the geographical implications of this ancient coastline were long-lasting. After the Younger Dryas, the sea level rose and these less densely populated eastern and south coastal parts became more accessible to Rox’s son Ruy (as we shall see in the next chapter).

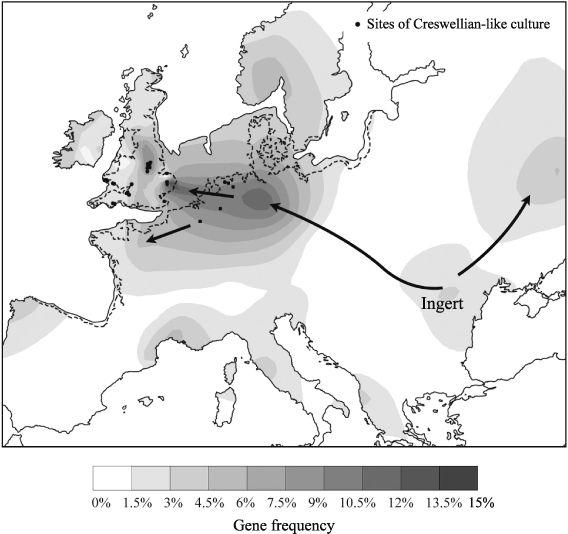

So, in the Late Upper Palaeolithic, after the LGM, the eastern side of Britain is rather quiet with respect to input from the Basque refuge. Instead, from the European mainland came another male gene group, Ingert (group I1c – see p. 124), who originated in the Balkan Ice Age refuge. Ingert is characteristic of north-west Europe, but particularly northern Germany and eastern England, although found at rather low rates (maximum 13%) even there.

58

This early intrusion from the east has a bearing on one of the issues that is central to our story of British origins: the apparent similarities between England and the parts of the Continent that face us across the North Sea, such as Holland and Frisia. Is the North Sea genetic fellowship we see today a reflection of Anglo-Saxon invasions or of something older? Several studies have shown that measurements of genetic distance (these are based on similarity of specific gene frequencies – see

Chapters 6

and

11

), depending on the relative frequencies of the broad male gene groups, always tend to place Frisia very close to East Anglia and Norfolk (see

Figures 11.2b

and

11.4b

).

My re-analysis confirms the general trend of similarity across the North Sea. However, there are older reasons – and evidence

– for this genetic neighbourliness than a massive swamping of England by Anglo-Saxon invaders from north-west Europe during the Dark Ages. The drowned North Sea Plain is one of the oldest geographical indicators of the beginning of an eastern British identity, and there is genetic evidence to support this.

At the time of the great post-LGM European expansion of 15,000 years ago, there was no North Sea. Instead, there was a flat grassy plain stretching all the way from Poland and the southern Baltic, through southern Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Frisia and Holland across the North Sea and into eastern England (

Figure 3.3

). In fact, had they wished, our forebears could have walked in a straight line all the way from Berlin to Belfast, although in practice they seemed to prefer wandering along beaches.

If it still existed today, the North Sea Plain would be in the centre of the Ingert distribution (

Figure 3.8

). Ingert dates overall in Europe to 21,000 years and may have originated in a Balkan Ice Age refuge (see below).

59

Three British founding clusters from Ingert (I1c-1, 2 and 3) date to around 13,000, 14,000 and 12,000 years ago, res pectively.

60

This suggests a pre-Younger Dryas (i.e. Late Upper Palaeolithic) spread for at least part of the Ingert branch. While Ingert is present at a low rate of about 3.3% throughout the British Isles, this figure rises to over 10% on parts of the English north-east coastal region, in particular York and Norfolk. Given this distribution, the age of Ingert in the British Isles,

61

and the fact that he is no more common on the neighbouring Continent, the chances are that this represents the echo of an ancient intrusion. To me this is the first of a series of specific, dated, early British genetic intrusions from the Continent which tend to mitigate claims of a later Anglo-Saxon genocide.

There is in fact some archaeological evidence for cultural links between the North Sea Plain Continental cultures and the Creswellian sites of Norfolk and Kent in the final stages of the Late Upper Palaeolithic, before the Younger Dryas. This would be consistent with the distribution and age of Ingert there (

Figure 3.8

).

Figure 3.8

Ingert (I1c gene group), the earliest Balkan males to reach Britain? This map shows the distribution of Ingert, a sub-group of Ivan, who most likely originated near the Black Sea and started spreading to north-west Europe just before the Younger Dryas freeze-up 13,000 years ago and continued during the Mesolithic 11,500 years ago. Black dots indicate finds of Creswellian style artefacts, dating to just before the YD both sides of the North Sea.

Apart from the Ingert story, much of the apparent ancient similarity between Frisia and Norfolk relates to shared Ruisko gene lines, derived in parallel from Iberia. This linkage can also be explained from the perspective of the drowned North Sea Plain. As we have seen, the first hunters to return up north from Iberia, along the Atlantic coast, would have found themselves entering a hugely extended continental shelf. Arriving at a point halfway between the tips of what are now the peninsulas of Cornwall and Brittany, they would have split at the mouth of the River Seine, which then flowed south-west out of the dry bed of the English Channel.

Those crossing the Seine would have continued along the Atlantic coast towards a vast flat region which has now shrunk back to the more raised regions consisting of Cornwall, southern Ireland and Wales, while the others continued up the river basin now occupied by the English Channel. The genes of those who turned west would form the main stock of today’s Atlantic fringe ‘insular Celts’.

The descendants of those who went up the old Rhine– Thames–Seine–Channel river would become the prehistoric East Anglians, Dutch and Frisians, while their vanguard would continue into Germany and Poland. In this Late Upper Palaeolithic recolonization scenario, which is implied by the Creswellian archaeological links across the North Sea, it would not be surprising to see some genetic similarities across the North Sea, but they would reflect ancient cousinship rather than any more recent west-to-east gene flow.

This scenario does seem to be borne out in the pattern of Ruisko gene types found in Frisia and England. The apparent similarity between Frisia and eastern England results, largely,

from a similar broad mix of shared gene groups and Ruisko gene types which were derived independently from Spain. After removing these matches from the analysis, there are no other Ruisko gene types which are shared between Norfolk and Frisia, and only a couple of matches elsewhere in Britain, implying a common Ice Age refuge origin rather than similarity resulting from later invasions. As we shall see in

Chapter 11

, the nature of this parallel relationship with Frisia contrasts with the situation for genes shared between eastern England and the Continental ‘Anglo-Saxon’ homelands, for which there is clear evidence for a small recent local east-to-west gene flow across the North Sea, in addition to the common southern refuge influence.

Theoretically, it should be possible to determine for every individual living in the British Isles approximately when each of their paternal or maternal ancestors arrived. What I am trying to do in this book is to put dates of arrival and numbers (i.e. relative fre quency) to those ancestral founding gene lines, as represented in today’s population. Clearly, the deep time perspective and the size of ancient male and female recolonizations of north-west Europe rather blunts simplistic claims, based on similarity of genetic markers, that the ancestral insular-celtic languages must have come from Spain, or that English results from a replacement of Celts by Anglo-Saxons based solely on the extraordinary genetic similarity between people of the respective regions. This is partly because of the huge time gap since those recolonization events after the Ice Age, which means that whatever languages those early hunters and gatherers may have

spoken it was unlikely to have been celtic or Germanic. In fact, sub-structural linguistic evidence within both these modern branches of Indo-European suggests the oldest language of the British Isles may have been more like Basque.

62

I shall come back to this issue later in the story, when we look at the Neolithic and the Bronze Age.

Apart from confusing the language story, the substantial size of the Iberian contribution to the initial colonization of the Atlantic coast makes it important to assess the numerical contribution of each new arrival to the British Isles from the south of other related gene groups over the next 15,000 years. Clearly, we dilute any discussion of British roots if we do not attempt to get a better time resolution for each Ruisko cluster. There are several ways of looking at this aspect, but before doing that we should go back in the story to the rapidly changing climate following the initial recolonization.

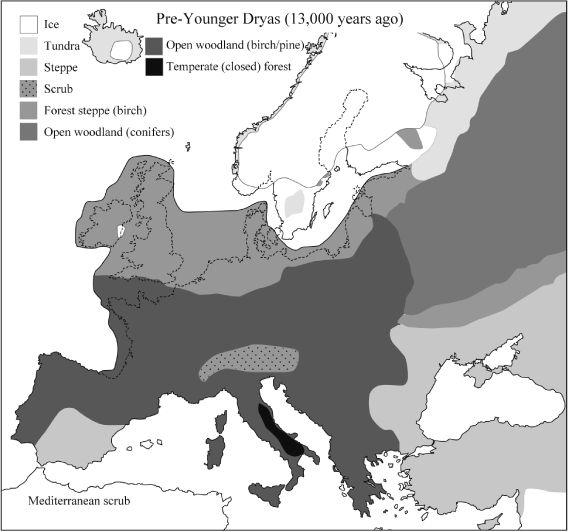

As average world temperatures worsened in a ratchet fashion from an immediate post-glacial high 14,500 years ago to a series of lows starting 13,000 years ago,

63

the grasslands of Western Europe were gradually replaced by steppe woodland. Central and Southern Europe were mainly open forest, while in the north and west, steppe forest predominated with sparse birch and pine (

Figure 3.9

). Paradoxically, with this increase in tree cover, archaeological traces of human activity in Northern Europe and Britain tend to decline slightly. Whether this resulted from the increasing variation in the weather caused by frequent wide temperature swings,

64

or just from the decline in open grassland for hunting, is a matter of speculation. One piece of evidence from Britain and Europe which could support the latter view is the later shift in the incidence of archaeological sites from the plains into low hilly country, where there were fewer trees.

65

The North Sea Plain probably remained as steppe, which may explain the expansion of Ingert into Norfolk apparently only shortly before the Younger Dryas cold event.

Figure 3.9

Pre-Younger Dryas climate map. This map of the climate just before the YD shows that, in spite of worsening weather leading up to the YD, open woodland cover had been increasing in Southern Europe. However, north-west Europe, including ‘Greater Britain’, still had some grassland (steppe – more suitable for hunting) with scattered birch forest.

Over the centuries leading up to 12,500 years ago, the weather became more and more erratic; it grew colder, and human activity declined. Around 12,300 years ago Europe plunged into another severe glaciation, known as the Younger Dryas – ‘Younger’ because there had been a couple of other chills in the preceding few thousand years, and ‘Dryas’ because the hardy polar wild flower

Dryas octopetala

flourished during these cold spells, and is detected in deposits by its pollen.

66

The Younger Dryas was extremely cold and arid, and lasted about 1,500 years. Ice caps re-expanded over Scandinavia, with a resulting fall in sea levels, and even reformed on the Scottish Grampians and the Pennines.