The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (58 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Obviously the extraordinary extent of the pan-European Viking spread, and the reasons for and ferocity of their seaborne attacks in the eighth to tenth centuries, were unique, and validate the continuing use of a special ‘Viking’ label rather than ‘Oh God! Not more Scandinavian raiders!’ But they were not the first people of Scandinavian origin in sea-going longboats to leave their mark on the British Isles, nor were they the last such Continentals to invade Britain, possibly carrying similar male genes.

Scandinavian longboats had been constructed, had travelled abroad, and had been under sail, far longer than the ‘Vikings’. As we have seen, Gildas described the invading ‘Saxon’ boats as high-prowed, sailing longboats. In the last chapter I linked the longboat burial at Sutton Hoo with its contemporaries, the Scandinavian longboat burials in Schleswig-Holstein, Denmark, Sweden and Norway (

Figure 9.3,

Plates 17 and 18). Among other common cultural clues, the Sutton Hoo burial lends the Anglo-Saxon invasions of eastern and northern England a distinct Scandinavian tint. Gildas gives us one of the earliest written statements that these ships could move under sail. As Barry Cunliffe points out, ‘Sleek, elegant vessels of clinker-built construction, with planks sewn together, are known [from Nydam, Denmark] as early as the fourth century

BC

. By the fourth century

AD

the

overlapping edges of the planks were clasped by iron nails, and paddles had been replaced by rowing oars.’

1

The same high-prowed sailing longboats appear on the famous Bayeux Tapestry as used not only by the Norman invaders, but also by Saxon King Harold before his defeat and death.

Scandinavians honed their sailing skills over many centuries as vital for communication in a land of high mountains strung along fjord-scored coastlines. It may have been improvements in sailing techniques that widened the range of raiding. A complex of other reasons have been suggested to explain the Viking era.

2

Knowledge of the pickings for plunder south and west must have been a spur, but there was also trade and increasing land-hunger in the narrow coastal strip backing onto the high mountains of the hinterland.

Earlier in this book, I discussed the genetic evidence for significant Scandinavian intrusions into Britain, especially the north, during the Neolithic Period. I shall come back to the genetics of the Vikings a little later; meanwhile, it is important to realize that attention-grabbing television documentary titles such as

Blood of the Vikings

should carry a health warning in the small print: not all Scandinavian gene markers need have been imported to the British Isles by Vikings.

Although historical contact

3

between Norway and northwest Britain began in the seventh century

AD

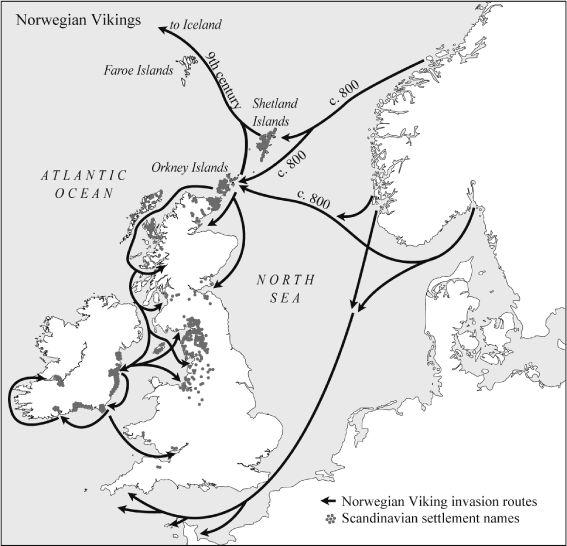

, serious raiding started from the last decade of the eighth century and built to a terrible crescendo in the following seventy years. Norwegian Vikings extensively attacked the western half of the British Isles (

Figure 12.1

) almost exclusively affecting what are regarded today as Celtic lands in northern and western Scotland, Wales, Cornwall and Ireland, extending down the Atlantic coast to Brittany and Spain. Cunliffe suggests that the early Viking colonization of north-west Britain was largely completed during the eighth century, providing a springboard for more juicy prizes in the monasteries of Ireland.

Figure 12.1

Viking invasions in the west. Norwegian Viking invasions and Scandinavian settlement names concentrated on Shetland, Orkney and the western side of the British Isles, particularly the Western Isles, Cumbria, Lancashire and Ireland.

That England was initially avoided by both Danes and Norwegians is in itself curious: possibly it was because previous alliances between the Anglian kings of England and their cousins in Denmark held from the sixth century, as implied by the

context in

Beowulf

(and by mention there of the names Offa, Finn and Hengist),

4

were initially still active. That perspective would tend to support the view that the

Beowulf

oral saga was originally created before 793 (the year of the sack of Lindisfarne) rather than after 850, when a new order was established in the Danelaw.

Somewhat later than the Norwegian onslaught, starting from the beginning of the ninth century, the Danes threw out cousinly values in the pursuit of booty and glory and adopted the same tactics as the Norwegians. Commencing by attacking their immediate neighbours in Saxony, they moved on to Frisia, then to the Frankish kingdoms, and on to England and France. All hell was let loose, and Viking raids became a free-for-all, the longships sailing out from both Norway and Denmark to scour the coastal regions of Europe for plunder.

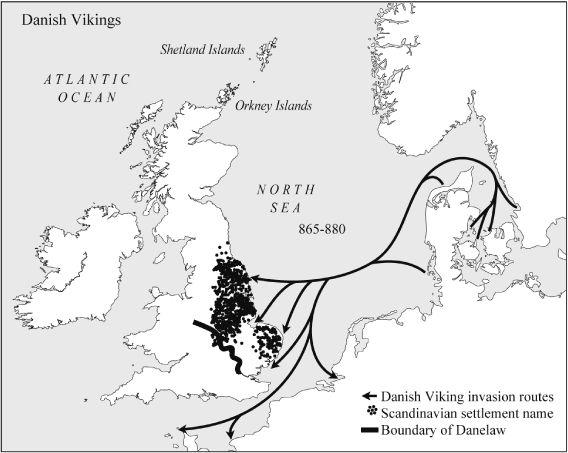

Danish attacks on eastern and north-east England and up the River Thames intensified from 830 onwards, developing into a territorial repeat of the Anglian invasions that began four centuries before. In 865, a large Danish army invaded East Anglia and overwintered there. Consolidating their base of operations, they went on, over the next five years, to conquer and settle East Anglia, Northumberland and northern Mercia, much as their former neighbours the Angles had done (

Figure 12.2

). And similarly, apart from forays up the Thames and Severn, the Danish Vikings were unable to gain any foothold in the non-Anglian, traditionally Saxon areas of southern England.

This repeat demarcation – or palimpsest, to borrow a term used earlier – of settlements between former Anglian lands and Saxon territory, the latter defended by revitalized fortifications of the old ‘Saxon shore’, seems quite a cultural and historical

coincidence. It cannot be simply explained by King Ælfred’s stout defence of the South, since the Danes never settled there at all. Essex is a geographical exception that could prove this rule. Although Essex was a vulnerable and isolated Saxon pocket north-east of the Thames bordered by East Anglia, unlike Norfolk and Suffolk it was never settled by Vikings (

Figure 12.2

). This was in spite of the fact that it was ultimately included under the Danes’ control, north of the agreed Danelaw line. That may tell us something about the effect of common culture on ease of conquest and settlement. Geographically, Angeln is a stone’s throw from Denmark, and it was the Anglian rather than Saxon territories that fell so quickly to the Danes.

As we have seen, there tends to be some overlap between genetic markers held by the Danes and those of other Germanic-speaking peoples of north-west Europe, but the northern Norwegian markers are more clearly recognizable. However, none of these male markers have labels such as ‘Neolithic Scandinavian’ or ‘Iron Age Viking’ written on them in ink. So again it becomes important to try to identify when such markers arrived and from where.

As I mentioned above, by using the phylogeographic approach I have managed to identify just three founding clusters that date to the historical period.

5

Two of these are of Scandinavian origin and account for 5% of extant male lines in the British Isles (

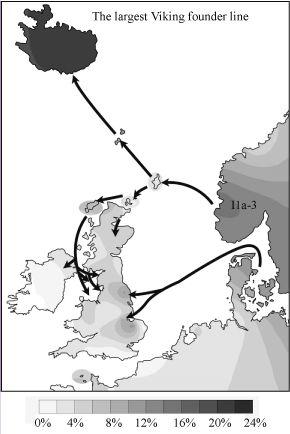

Figures 12.3a

and

12.3b

). Given the stringent criteria applied in the identification of these most recent founder clusters, this figure is likely to be an underestimate, but it is somewhat greater than for the Anglo-Saxon intrusion, given that I could not identify any clear Anglo-Saxon founding male clusters. Gene-type matches reinforce this measure of Viking influence – as we shall see.

Figure 12.2

Viking invasions in the east. Danish Viking invasions concentrated in East Anglia and north-east England, particularly York. The Danelaw Line is shown as well as Scandinavian settlement names in eastern Britain. The latter are much more numerous than Viking graves, which have a more coastal distribution (not shown).

Since there was already a geographical overlap between the Anglian territories of eastern Britain (discussed earlier) and those invaded by the Danes, I shall consider the Danish Vikings first. Danish gene type matches account for 4.4% of the entire British sample, which is marginally greater than the similar figure of

3.8% for Anglo-Saxon matches.

6

Of the three British founding clusters of the historical period, one, I1a-3, was identifiable as a founding gene line from Denmark and its derivative British cluster. Although found elsewhere in Britain, particularly on the east coast, I1a-3 points to a clear founding event in Fakenham, west Norfolk (

Figure 12.3a

).

7

This cluster dates to around 1,200 years ago.

8

It is found throughout the areas known to have been raided by Danish Vikings, and also to some extent in Norwegian Viking colonies on the west coast of Britain. The latter may be explained by overlap between Denmark and nearby southern Norway in the distribution of the founding gene type for this cluster.

9

This is reflected in the map (

Figure 11.5c

) by the presence of ‘Danish matches’ in Scotland, its islands, and west-coast Britain traditionally associated with Norwegian Vikings.

10

It might be thought that, with so many different inputs from related north-west European groups, any differentiation between sources of gene flow would have been lost. Yet some pattern persists. In line with overwhelming historical and place-name evidence (

Figures 12.1

and

12.2

), male intrusive gene types in York and Norfolk are more characteristic of northern Germany and Denmark than of Norway (ratio of NGD to Norway 27:5; compare

Figures 11.5b

,

11.5c

and

12.4

).

If we look at shared gene type matches between Denmark and the British Isles, we can see this pattern of distribution in more detail (

Figure 11.5c

). Danish-linked gene types are found in several parts of England, but in a patchy distribution rather different to that of the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ matches. They are nearly absent, for instance, from the parts of East Anglia (North Walsham) and Sussex coasts previously identified by the Romans as the ‘Saxon shore’. Conversely, they are most common in York and around the Wash. Their highest rate anywhere is in a single pocket in the west Norfolk town of Fakenham, making up 19% of the sample.

11

Most of these latter belong to the same gene type and constitute part of the Danish founding cluster I1a-3. The frequency of Danish gene type matches in the areas under the Danelaw in the late ninth century is consistent with the density of archaeologically visible Viking settlements in those areas.

12.3a–c

Three British male genetic founding clusters of the historic period, none of which clearly relate to the Anglo-Saxon Advent.