The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (56 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

So, it is essential to check for similarity by common descent before opting for genocide. What the story shows so far is that correlations of gene frequency mean nothing without a basic model (and knowledge) of the genetic prehistory of the regions in question. Weale’s and Capelli’s studies generated certain models based on historical perspectives of Procopius and Gildas and then selected the genetic populations against which to test those models. If circularity is to be avoided, effective models need to be derived primarily from genetic, climatic and geographical information, not driven by narratives drawn from recent history or archaeology.

We cannot assume the similarities or differences of the various British tribes from their neighbours to be the consequences of controversial historical events of the recent past if we do not have some idea of what went on before. Patterns of gene group frequencies on their own cannot be given a date, but are usually the final result of a number of different events that took place at different times. Even splitting up the gene groups into numerous gene types in an attempt to define regions more precisely brings its own problems if no attempt is made to produce genetic trees and date expansions and movements of branches.

The phylogeographic approach to genetic prehistory that I have used in this book aims to reconstruct a genetic history of individual gene lines and their movement from source regions to target regions. This means first examining the representation of

the branches of each line in different regions in order to establish the source and target. The second part is dating the branch points and the gene line movements. Increased resolution of the Y-chromosome gene tree using STR gene markers makes it possible not only to get a more informative tree, but also to get date estimates on the branches.

To summarize, the phylogeographic approach establishes three broad aspects of West European and British colonization in the past 16,000 years which have a bearing on the Anglo-Saxon question. First, all but a few per cent of male and female gene lines appear to have arrived in the British Isles

before

the historical period (i.e. before the Anglo-Saxons). Second, most British colonizers, including about two-thirds of

English

ancestors, came from the Iberian refuge soon after deglaciation, or at least during the Mesolithic. And third, the

subsequent

colonization of the British Isles during the Neolithic and the Bronze Age was complex in time and space, but mainly came from the other side of the North Sea.

Eastern England received some input from the Balkans via the Danube and the North European Plain during the Mesolithic, and considerably more during the Neolithic from the same region and also increasingly from southern Scandinavia. The Bronze Age saw further development of this trend in eastern Britain, and Wessex and the south coast began to receive more gene flow from north-west Europe. This sequence of dated, incoming, prehistoric male lines does not leave much room for the culturally dramatic invasions of the past two thousand years.

Clearly, not all geneticists may agree with my critique of the Weale and Capelli research or with my summary of the complex pre historic interplay between the now Germanic-speaking areas of Europe and Britain, but my findings ought to be independently replicable. In summer 2005 I presented a paper at a Cambridge symposium on methods of simulating and estimating migrations, and was amazed to hear a paper given by Cambridge geneticist Bill Amos which had come to some similar conclusions to mine but used a completely different mathematical approach and dating methods. Amos and his colleagues clearly felt that simplistic models like Weale’s were unsatisfactory, and that knowing and understanding the history of previous population mixes in the north-west European region was an essential prerequisite, and that this had not been addressed by Weale or Capelli.

34

I shall not go into detail of their complex, novel yet robust approach to dating multiple admixtures between the Continent and Britain, but merely quote from their discussion, as they pose the problem so clearly. I preface this quote by explaining that Amos’s definition of Anglo-Saxons, for the purpose of his analysis (and to be open-ended about dates), were people who had come over from north-west Europe carrying male genes at

any

time in the past ten thousand years, rather than the more conventional Gildas concept of sons of Saxon wolves who ravaged England in the fourth and fifth centuries

AD

. Also, when he refers to a ‘time slice’ he means a reconstruction of previous admixture and affinity between populations at various specified times in the past.

An important question raised by this analysis concerns when Anglo-Saxons came to England … was it through one major influx following the collapse of the Roman empire or were there earlier incursions? Overall, English towns are tightly linked to NGD and Friesland, samples collected from the Anglo-Saxon homelands, but this affinity tells us nothing about when the Anglo-Saxons came across nor how long the settlement took. However, there are two reasons for suspecting it was earlier rather than later. First, in all but the deepest time slice, NGD and Friesland tend to cluster as a pair, suggesting stronger links between these two than between either one and England. Such a pattern is most consistent with NGD and Friesland being continental neighbours with greater exchange between each other than across the channel with England. The second point relates to the deepest time slice, where NGD joins to Europe rather than Britain, suggesting reduced links. At this point, Friesland is indistinguishable from a number of towns that together form a very shallow English clade. Such a pattern could arise either if mixing with Friesland began earlier than with NGD or, in view of the extremely shallow English clade, if at this point the English and Frisians were one and the same. Taken together, therefore, our analysis appears to favour a history in which Anglo-Saxons arrive in Britain considerably before 4–6th centuries, possibly as a group of Friesians who moved across 5–10,000 years ago (depending on the time calibration).

35

To précis and oversimplify the final point, Amos is saying that the affinity and migration between Friesland and England is likely to be much more ancient than that with the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ homelands – at least going back to the Neolithic Age. Amos was not able to resolve any more recent gene flow, given the gaps between his time slices, but we are now collaborating to look at that question.

Back to my own study. After estimating ages for all the constituent clusters of the main British founding haplogroups, there were only three founding clusters dating to the historical period of the past two thousand years. Two of these originated in Scandinavia, one from the south and one from the north. None of the three, however, could be identified with the putative homelands in north-west Germany (Saxon) or Schleswig-Holstein (Angeln) as

sources

, or with Norfolk in particular as a

target

(

Figure 12.3

). This does not necessarily mean that there was no invasion from those homelands, Anglo-Saxon or otherwise; merely that I could not detect it by looking for and dating specific recent genetic founding events.

There are several possible reasons for this lack of evidence, the main one being the short time period available to create detectable founding lineage clusters in Britain by random mutation.

36

The existence in England of members of a common founder line originating on the Continent does not necessarily tell us when it came, unless there are unique new mutations in England that can be used for dating. This would be even more difficult if the founding size was relatively small and recent.

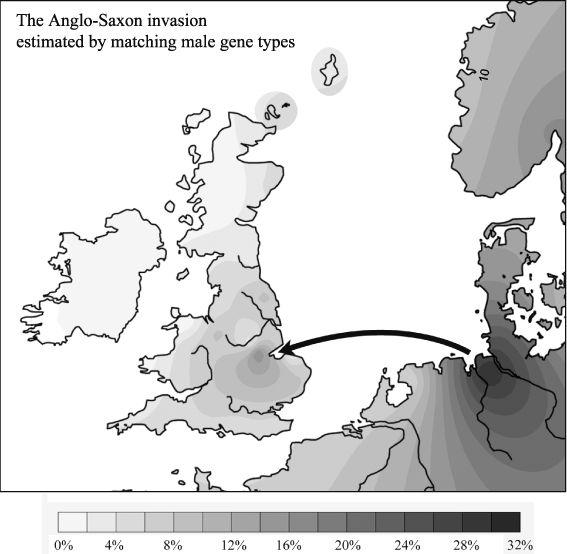

Having, so to speak, scraped the male barrel looking for a genetic founding event to match the Anglo-Saxon invasion, I felt that there was one other possible way to exclude significant specific migration. That was to look for exact gene type matches between

the samples from the British Isles and each of the various putative Continental sources (Iberia, the Anglo-Saxon homeland, Norway, Denmark and Frisia). This is in a sense taking a leaf out of the archaeologist’s book, of matching cultural items in different places, but instead using unique male gene markers. To identify the most likely Continental sources of particular gene types, I was able to refer to my earlier network phylogeographic analysis of lineages, described in this book and its Appendices.

This approach has its pros and cons. The main advantages are that full use can be made of the very detailed information provided by the STR gene types, and recent mass migration would be expected to produce such exact matches. The main disadvantage of this quantitative matching approach is that it cannot make full use of available information on time depth. There is also likely to be some gene type overlap between the different Continental source regions (Figures 11.5 and

12.4

).

37

I can honestly say that I did not hold out much hope for this approach, reminiscent as it is of the ‘happy families’ card game, and given the sampling issues. So it was a surprise when there were very specific results. I shall come back to the Norwegian results (

Figure 12.4

) a little later, since their distribution seems generally more appropriate to locations of Norwegian Neolithic and Viking raids, but any specific matches found for Frisia, Denmark, Schleswig-Holstein or north-west Germany could theoretically be relevant as possible Anglo-Saxon intrusions. As it turns out, there were none for Frisia (see below), so that is not shown as a figure.

Since Denmark was clearly different on the genetic distance map (

Figure 11.4b

), and had a different mix of haplotypes from Schleswig-Holstein (Angeln) and north-west Germany, I treated it separately from these two, which I combined in this analysis as the ‘Anglo-Saxon homeland’. They also fit the putative Anglo-Saxon homeland on cultural grounds (

Figure 9.3

). Figures 11.5 and

12.4

show the results of gene type matching from the south-west European source (

Figure 11.5a

) and the various North European sources: ‘Anglo-Saxon homeland’ (

Figure 11.5b

), Denmark (

Figure 11.5c

) and Norway (

Figure 12.4

). As might be expected, there is some degree of overlap of matched gene types between the different European sources of gene flow. The greatest degree of overlap is between Danish matches and Oslo ones in southern Norway, which is to be expected from geography and history.

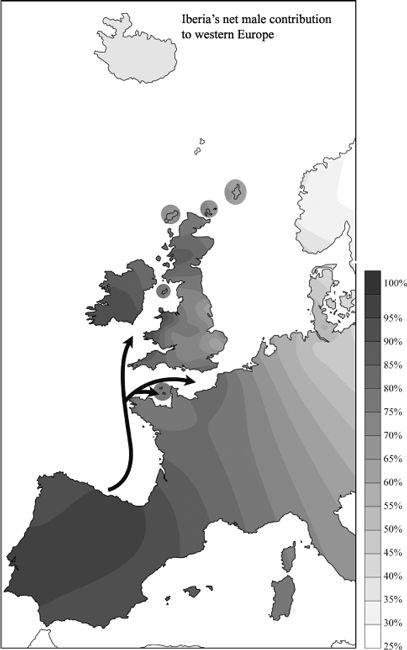

11.5a–c

Specific male intrusions from Europe into the British Isles (shown as three genetic frequency contour maps based on the percentage matching STR gene types between source and target areas: arrows indicate direction of gene flow based on gene types and geography).

Figure 11.5a

Intrusions from an Iberian source. By far the majority of male gene types in the British Isles derive from Iberia, ranging from a low of 59% in Fakenham, Norfolk to highs of 96% in Llangefni, north Wales and 93% in Castlerea, Ireland. On average only 30% of gene types in England derive from north-west Europe. Even without dating the earlier waves of north-west European immigration, this invalidates the Anglo-Saxon wipeout theory.