The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (26 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Clearly this east–west Saami mix makes any search for a single Mesolithic expansion source for Lapland problematic. Comprehensive genetic studies of the Saami suggest that Rostov entered

the eastern Fenno-Scandian Peninsula during the Mesolithic directly from Eastern Europe.

55

Supporting evidence that Rostov did not enter northern Scandinavia via Denmark comes from my analysis of the actual Rostov gene types. Denmark has not only less Rostov than Norway, but also a different spectrum of individual types.

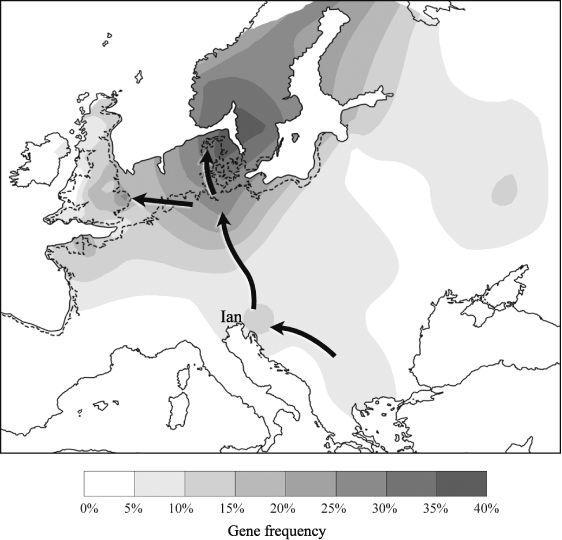

Geneticist Zoë Rosser of Leicester University came up with a possible reason for a more recent arrival of Rostov into Scandinavia through central Eastern Europe, suggesting horse-riding Kurgan nomads arriving from north of the Caspian Sea (

Figure 4.9

).

56

The main Rostov cluster that my analysis identifies in Norway (R1a1-2b) dates to 5,700 years ago (

Figure 5.7a

),

57

which would be consistent with this view. More simply, however, this cluster may signal the arrival of the Mesolithic down the Scandinavian Peninsula, and its later expansion during the Scandinavian Early Neolithic.

Either way, since Scandinavia is the likely source of British Rostov types, this east–west direction is of interest to us. The highest Rostov rates among Saami groups are in the Swedish Saami (20%) and Kola Saami (22%), possibly suggesting gene flow direct from Archangel in the European Russian Arctic into the Kola Peninsula and Lapland. This route would have more or less bypassed Finland altogether, which makes sense, since much of Finland would have been uninhabitable during the earliest part of the Mesolithic (

Figure 4.9b

). Such a route may also be inferred from Rostov’s unexpectedly low frequency among Finnish Saami (less than 3%) and among Finns in general (7%) (

Figure 4.10

).

58

A somewhat similar east–west pattern is seen for N3 (also called TAT), a Y-chromosome line which is absent from the

British Isles but characteristic of north-east Europe and accounts for 47% of Saami male lines. However, in this instance the distribution and frequency gradients of N3 in Northern Europe are rather different from those of Rostov, implying another source and route of entry to Lapland. Unlike Rostov, who is most common among Slavic groups and most likely arrived from Archangel, N3 is uncommon among Slavs, and is commonest in Finns (63%) and Finnish Saami (55%), together with a number of other similar groups, including other Finno-Ugric speakers, in north-east Europe (Finns, Saami, Karelians and Estonians), the Volga–Urals area and Siberia. Whether this north-westerly expansion of N3 occurred along with the spread and expansion of Finno-Ugric languages –

and

whether this happened parallel with or independently of Rostov during the Mesolithic, Neolithic or later ‘Kurgan’ periods – is a matter of speculation. I prefer the view that N3 expanded separately and later than Rostov, in which case it would be a better candidate for the much more recent Kurgan expansion from the region north of the Caspian.

59

N3 is uncommon in Scandinavia and never made it to the British Isles at all, while Rostov did

60

– and in sufficient numbers to help us determine the degree and locations of northern Scandinavian influence there.

Rostov is common among Norwegians. Also consistent with the hypothesis of its introduction via Lapland to the east, the frequency of Rostov declines north-to-south through Scandinavia from 37% in Trondheim up in the north, to 26% in Oslo and then down to 13% across the water in Denmark (

Figure 4.10

).

61

It consists of four related clusters, three of which can be dated as local founder events. The largest, cluster R1a1-2b, is 5,700 years old (

Figure 5.7a

)

62

and concentrates in northern Norway,

being uncommon to the south in Oslo or in Denmark. This is consistent with the archaeological picture of some delay before the supposed Mesolithic migration from Lapland established itself there.

63

The distribution of Rostov could reflect Denmark having been at the end of a founding event which spread from the south-east. More simply, however, Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein in northern Germany may have received their modest component of Rostov directly from Eastern Europe south of the Baltic (

Figure 4.9b

): the more southerly Rostov clusters in Scandinavia are much younger, with a modest Bronze Age date of 3,000 years ago. Whatever the prehistoric reasons for these differences, they are helpful in establishing which parts of Scandinavia acted as sources for migration to Britain and for dating those events.

In summary, on the basis of the putative male and female Mesolithic founder lines I have discussed so far, the ancestors of the Saami would seem to have arrived in Lapland via a tortuous East European route. In the process they suffered severe population bottlenecks and eastern male intrusions, keeping their West European female lines and swapping their Western male lines for mainly East European ones.

We can use this scheme of western and eastern Mesolithic genetic inputs to the Fenno-Scandian region to examine the make-up of Norwegians on the west coast of Scandinavia. While it is clear that there is a preponderance of eastern male lines among these populations, later to be counted as Vikings (see

Chapter 12

), this effect is less extreme than in the case of the Saami.

64

However, in the context of male lines found in the British Isles, new appearances of Rostov tend to imply a northern Scandinavian intrusion rather than a German or Frisian source (see

Chapters 11

and

12

). Specific Rostov gene type matches confirm this trend across the North Sea, which are more between Norway and Britain (and Iceland to the north-west) than between Britain and Denmark or Schleswig-Holstein in northern Germany. What is more, because of the previous ice sheet over Scandinavia, such an intrusive event would have to be Neolithic or later. As we shall see, Rostov’s Norwegian intrusion into Britain started early, during the Neolithic.

The Ivan (I) clan is nearly entirely confined to Europe, although he may have originated ultimately in the Trans-Caucasus around 50,000 years ago and initially spread into Europe before the Last Glacial Maximum, 24,000 years ago.

65

Since the age of the main Ivan gene group does not tell us when his sub-branches arrived in their target regions, the question remains as to exactly when the migrations did occur – soon after the LGM, in the Mesolithic (i.e. after the YD) or in the Neolithic. One problem is in determining where each of Ivan’s four main subgroups spent the last Ice Age. That would help tell us from where they each re-expanded after the Last Glacial Maximum – and when and where they each went after that. Whereas the Ivan gene group as a whole is pre-glacial in age, dates for the origins of his four main subgroups, although old, are all post-LGM,

66

suggesting that they may have re-expanded from one or more of

the European glacial refuges. The Balkans and the Ukraine both carry all four branches at sufficiently high rates and diversity, in my view, to make that whole region the most likely

composite

East European Ice Age refuge for Ivan.

67

The most comprehensive, up-to-date work on the male group Ivan in Europe comes from Estonian geneticist Siiri Rootsi and colleagues based mainly at the University of Tartu in Estonia.

68

All Ivan subgroups are present at appreciable frequencies in south-east Europe, an area including the Balkans and the Ukraine and encompassing the East European Ice Age refuges (

Figure 3.7

).

69

The highest frequencies of Ivan and his subgroups I1a, I1b* and I1c (Ingert) occur in the Balkans (overall, Ivan’s frequency is around 40% in Bosnia, Croatia and Slovenia), and around the north coast of the Black Sea (Moldavia at 28%, Ukraine and north Caucasus at 22–24%).

The only other regions with such high Ivan frequencies are north-west Germany for Ingert and southern Scandinavia, for I1a, which I therefore name

Ian

(pronounced ‘Yan’, a Danish version of ‘John’) (

Figure 4.11a

).

70

Ingert could have come from the Moldavian refuge before the Younger Dryas, up the Dnestr into Poland and then into Germany (

Figure 3.8

). Ian came rather later from slightly farther west in the Balkans, nearer to Slovenia, and then down the Elbe/Oder rivers towards Denmark, where he is now found at his highest rate, 37%.

Ian also encroaches on France and Britain, but at generally lower rates. One theory, based on diversity, is that this subgroup evolved separately in a Franco-Spanish LGM refuge, but this does not explain his absence from the Basque Country; neither does it explain his co-distribution with other Ivan subgroups, which suggests a birthplace in the Balkans–Ukraine region. My view is that during the LGM Ivan diversified in isolated local Balkan and Ukrainian refuges into his four main subgroups,

71

followed by a post-LGM dispersal of Ian and Ingert into Northern Europe.

4.11a–b

The men from the Balkans: Ivan’s sons in north-west Europe during the Mesolithic.

Figure 4.11a

From the Mesolithic onwards, Ian (I1a) expanded in southern Scandinavia, where he is now the dominant group, and also in northern Germany. He moved to Britain starting from the Late Mesolithic, and expanded there particularly during the Neolithic.

Ian and Ingert make up respectively 11% and 3% of the British population, mainly focusing in England and Scotland, and arrived much later than Rox in north-west Europe and the British Isles. Ingert, the minority subgroup of the pair, appears at least as old there as Ruy, dating to around the time of the Younger Dryas Event. This raises the question of how much of Ingert arrived in Western Europe and Britain

before

the YD and how much

after

it.

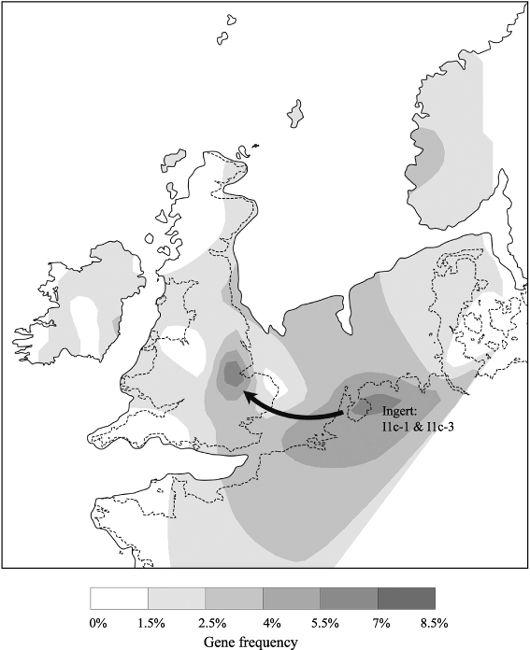

Figure 4.11b

Ingert (I1c) started expanding in north-west Europe from just before the Younger Dryas but continued during the Mesolithic particularly in Frisia, the Netherlands, eastern England and the North Sea Plain, as shown here (composite contours for I1c-1 and I1c-3 – arrow shows direction of gene flow based on tree).

Norfolk and East Anglia were still linked to the Continent during the Early Mesolithic. I have already introduced Ingert in

Chapter 3

, entering Britain from the east before the YD when the North Sea was a grassy plain. The main representation of Ingert is in northern Germany and the areas bordering the North Sea, including eastern Britain, southern Scandinavia, Holland and Frisia. The degree of diversity emerging with new Ingert clusters in north-west Europe suggests an initial pre-YD migration into the north-west,

72

which logically fits with its main representation, centred in northern Germany, and relative under-representation in Scandinavia, which was ice-bound at the time (

Figure 3.8

). A post-LGM origin for Ingert, near the Black Sea, probably in Moldova), with a pre-Mesolithic migration and expansion north-west probably up the Dnepr then looks likely. Two of the three Ingert clusters show further Mesolithic expansions into Britain just after the YD event.

73

I1c-3, for instance, dates in Britain to just after the YD and features both sides of the North Sea: in Norfolk and the Fen country, and in Frisia (

Figure 4.11b

).

74