The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (32 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

With the notable exceptions of north and south Wales, Ian is found throughout Britain, even in the heart of Scotland at rates of 9% and above. The highest rates are found on the east coast of England and around the Wash (over 30%), followed by 20% in the Channel Islands and 15% in central southern England, although the south coast sample sites from Penzance to Kent only have around 10% Ian.

In the same way as with the Ruslan lines, Ian can be split into a small tree of clusters (

Figure A5

, Appendix C). There are seven of these, of which three large ones, I1a-2, 3 and 4, dominate, accounting together for three-quarters of British Ian types. One of the two largest of these clusters, and by far the youngest in Britain at approximately 1,200 years, is I1a-3 (30% of British I1a). I1a-3 derives from southern Scandinavia, centring in the Bergen/Oslo region, where it dates to the Bronze Age.

74

By evidence of this date and its coastal distribution round Britain, I1a-3 is a good candidate for a genetic component for more recent Norwegian invasions of the British Isles. I shall discuss

later whether these migrations were entirely defined by the historical Viking raids (see

Chapter 12

).

75

A much smaller cluster, I1a-5 (5% of British Ian),

76

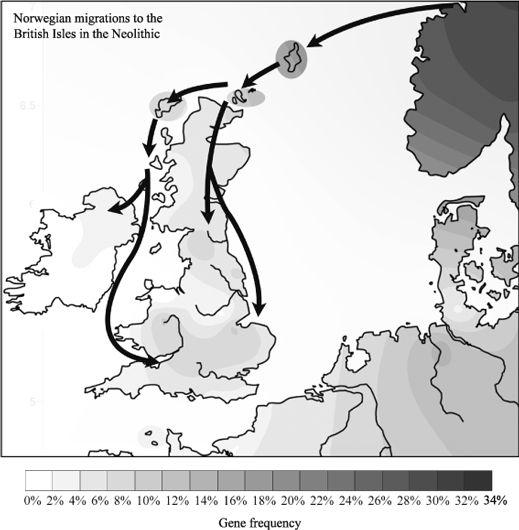

like R1a1-2 and the maternal British J1b1 gene line, derives from farther north in Norway, and dates to the Neolithic in northern Britain, being found particularly in the Western Isles of Scotland (6%) (

Figure 5.7

).

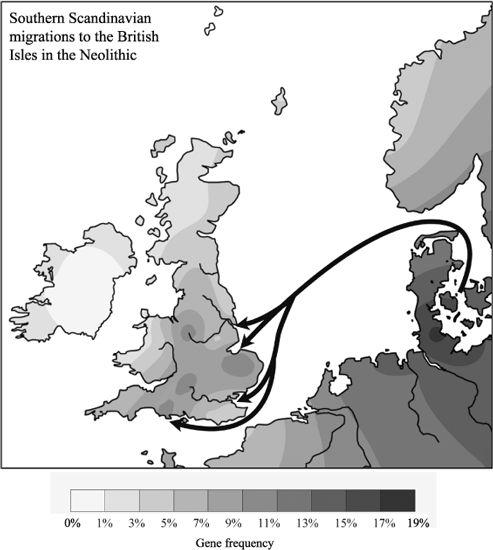

5.7a–b

Scandinavian male migrations to Britain during the Neolithic.

Figure 5.7a

Norwegian Neolithic arrivals in Britain did not just enter Shetland, Orkney, the Western Isles, eastern Scotland and Cumbria in the north, but penetrated as far south as Norfolk, south Wales and the Megalithic centre of Wessex (composite of I1a-5, I1a1–4 and R1a1–2a&b).

Figure 5.7b

Migrants from southern Scandinavia and Schleswig-Holstein targeted the same regions of England during the Neolithic that the Angles did later in the Dark Ages, but they visited Wessex as well (composite contour of: I1a-291b, I1a-7b, I1a-6b and R1a1–1).

The largest British cluster is I1a-2 (32% of British Ian) (

Figure 5.7

).

77

Although this cluster is found throughout Scandinavia, it centres more on Schleswig-Holstein and north-west Germany (part of the putative Anglo-Saxon homeland) at 14%, and to a lesser extent in Denmark south of the Baltic mouth (9%), spreading also to Frisia (6%).

78

This cluster dates to the Neolithic

in Britain, with a wide distribution but concentrating mostly in England including the northern part. So, although I1a-2 features in the so-called Anglo-Saxon homeland, its age, distribution and unique diversity in England suggest that much of the movement had occurred during the Neolithic. This was

long

before Gildas’ ‘Three long-boats’ (see p. 305) arrived to herald the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ advent.

Cluster I1a-4 also characterizes southern Scandinavia. But like I1a-3 – and unlike I1a-2 – it favours Oslo (9%) and Bergen (8%) rather more than Denmark and Frisia (4% each). Like I1a-2, I1a-4 has a scattered distribution in eastern England and around the British coast, and an age suggesting a Neolithic or Late Mesolithic entry (

Figure 5.7

).

79

I1a-7 is the most southerly of the Ian clusters, having a centre of gravity well below Norway. However, it lacks a clear Danish identity, being found equally in Denmark, north-west Germany and, particularly, Frisia, with isolated instances in northern Scandinavia, Switzerland and France. In frequency and diversity,

80

I1a-7 is more British than Continental. It has a Bronze Age date in Britain accounting for 9% of British Ian types.

81

As we shall see in

Chapter 11

, there are a number of reasons for rejecting the notion that the presence of Ian in England and eastern Britain is simply a reflection of the much later Anglo-Saxon or Viking invasion. Not the least of these counter-arguments, apart from the genetic dates of the clusters, is the observation that, as with Ingert, where there are exact British Ian gene type matches with the Anglo-Saxon homeland these have overall

low

frequencies in England. Furthermore, unlike the rest of Ian’s British distribution, the matches are limited in distribution to those areas of eastern England in which we might

expect, from Dark Ages and Medieval chronicles, to find them (see

Part 3

).

This very limited vindication of the extravagant claims of monks such as Gildas in the Dark Ages in no way explains the even distribution of Ian throughout the rest of non-Welsh Britain. What is more, there is a clear differentiation between north and southern Britain in terms of their Neolithic Continental Ian source. For instance, as mentioned above, Scotland derives its two most characteristic Neolithic clusters, I1a-5 and R1a1-2, from northern Scandinavia (

Figure 5.7a

), appearing to match in frequency, date and origin the unique Neolithic J1b1 maternal entrant from the same region. A further argument against Scottish Ian being mainly a later entry, perhaps with the Vikings, is that the even distribution of Ian throughout Scotland is not matched by the uneven distribution of R1a1, which, like the Vikings, concentrated on the coast and offshore islands.

In summary, whether we look at eastern England – where Ian reaches his highest frequency of 32% in Fakenham – or the rest of England and Scotland, Ian seems to provide evidence of an extensive Neolithic gene flow from north-west Europe. This Neolithic influence shows a clear bias towards Scandinavian sources, both northern and southern, rather than north-west German or Frisian sources. Only cluster I1a-3 gives clear evidence of recent invasion. It constitutes 30% of British Ian types and between 8 and 11% of all male types in parts of eastern England (see

Chapter 12

).

82

These findings have significance for more than the Neolithic period. The Ivan group, of which Ian makes up a large part in the West, is the main Y gene group signalling male gene flow through north-west Europe, but his presence in England is part of the nonspecific evidence used for an interpretation of the Anglo-Saxon

invasion as a massive ethnic cleansing event in England.

83

These new figures would suggest no more than a 4–12% Dark Age component for this particular male line in England (see

Chapter 11

).

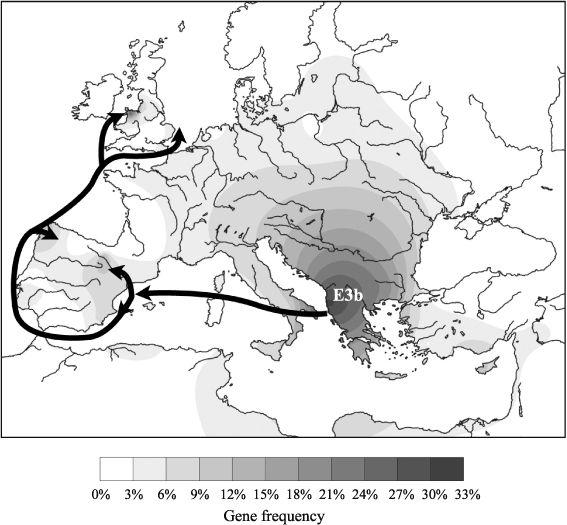

Other male gene groups associated with the Near East Neolithic are E3b and, confusingly, a male J to match the maternal J line. Like the latter, they both feature on the Mediterranean coast, but unlike maternal J they are rare in Germanic-speaking mainland north-west Europe.

E3b originally arose in East Africa around 25–30,000 years ago. The commonest non-African sub-group of E3b, ‘E-M78’ probably also arose in East Africa as well, around 23,000 years ago and moved from there to the Near East shortly after the Ice Age around 15,000 years ago. E-M78-α, is nearly the sole sub-cluster of M78 found in Europe and is a Neolithic trail-blazer. But its Neolithic expansion did not take off from the Near East. It may have arisen first in Anatolia, where it is found at low rates, but E-M78-α features most strongly in the Balkans at rates of 20%–30% (

Figure 5.8a

), showing a population expansion around 7,800 years ago during the Neolithic of that region. So although E-M78-α’s most important numerical expansion was during the Neolithic, it took place in the Balkans from whence it moved west along the Mediterranean coast of Southern Europe via southern Italy. From Italy, E-M78-α moved to south-west France, Catalonia and Valencia, thence round Gibraltar to Galicia in western Spain (

Figure 5.8a

). Farther up the Atlantic coast, E-M78-α (detected as E3b) reappears again at appreciable rates of 5–10% in southern Britain (England, Wales and the Channel Islands, but excluding Ireland and Cornwall), with a

high point of 33% in Abergele in Wales. As we shall see, the link with Abergele has connections with the spread of copper mining in the Neolithic. Given the distribution of E3b, this stretches metallurgy link from Wales back to the Balkans.

Like I1b2, this uniquely European sub-cluster of E3b is also a putative human vector for celtic languages from Italy and/or the Balkans, albeit with a slightly different trail. But even when combined together, these two male lines from the Balkans hardly show an overwhelming intrusion to the British Isles, ranging from 0% to 5.5%, with the only exceptions being Abergele at 33.3% and the Channel Islands at 7%. Ireland only has I1b2, which ranges from 0% to 2.6%. The male gene group J, in particular J2 which is the predominant J sub-group in Europe, has a similar European history to E3b in that it came into Europe from the Near East and moved west along the Mediterranean coast to Italy and the Spanish regions of Catalonia, Valencia and Galicia en route to the British Isles. However there the similarities end. First, the centre of J2 Neolithic expansion and highest frequency was from the Levant and Palestine rather than from the Balkans (

Figure 5.8b

). Indeed J2 may have originated in the Levant before the last Ice Age. Three branches of J2 spread west along the Mediterranean. One of these (M102*), like I1b2 and E-M78-α, appears to have taken the Balkan route (via Albania) to Italy (northern Italy in this instance), ending up in Bearnais in south-west France without circuiting Spain. The other two (M67* & M92) can also be traced strongly to Italy, with a more southerly centre of gravity. They both appear to have started their journey directly from the Levant and Anatolia, largely bypassing the Balkans and eventually spreading round Spain, one (M67*) to Catalonia, Andalusia and Galicia; the other (M92*) moved to Valencia, Andalucia and Galicia (

Figure 5.8b

). They by-passed the Basque country and are both represented in southern England and in Scotland. Ireland was missed out completely by this intrusive Mediterranean Neolithic marker, receiving nearly exclusively Ivan lines from north-west Europe (and not many of them) instead of E3b and J2.

Figure 5.8a

E3b: Male Neolithic gene flow west from the Balkans along the Mediterranean. Although E3b is ultimately of East African origin, its European sub-cluster (E-M78-α) expanded in the Balkans during the Early Neolithic 7,800 years ago. Part of this expansion travelled via Italy and then round Spain, eventually arriving in the British Isles, including a major founding event in north Wales. E3b is a putative geographic associate both for the spread of Cardial Ware pottery and for celtic languages (

Figures 5.1

&

2.1b

).