The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (45 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

One explanation of the dramatic difference in numbers of celtic inscriptions between England and the rest of the British Isles is that by the time Romans left, the inhabitants of England no longer spoke celtic, having changed over to some version of Latin, perhaps like the French. This rationalization is becoming increasingly popular, although it is still a controversial minority view. The evidence for it includes some British Latin loanwords

in Anglo-Saxon and a small number of Latin place-names adopted by the Anglo-Saxons. The main problem with this explanation is that one would expect to see, in England as in Wales, Latin inscriptions continuing after the Roman withdrawal – which is not the case. Also, the low number of borrowings needs some other explanation. Although there are considerably more Latin than celtic loanwords in early English, the figure of two-hundred-odd is still very small when compared with the massive effect of the Norman invasion on English.

Given that neither Latin nor celtic words intruded much into Old English, there is the possibility that a third, pre-existing and more closely related (i.e. Germanic) language survived in England during Roman times, one which could hybridize more easily with the incoming Germanic influences from the Continent. I shall look at the evidence for this in the next chapter.

AS THE FIRST

E

NGLISH NEARER

N

ORSE OR

L

OW

S

AXON?

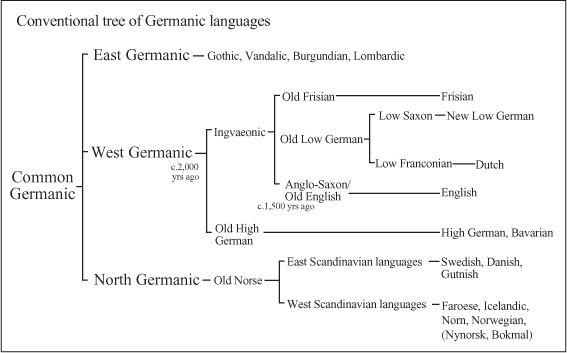

Imagine that English was spoken during Roman times. What would it sound like, and which languages on the Continent would it affiliate to? Nearly all linguists would view this as a silly question. The orthodoxy sees ‘Old English’ not as indigenous to England, but as the direct descendant of a Continental Germanic language, ‘Anglo-Saxon’, introduced for the first time into England by Germanic-speaking Anglo-Saxon invaders in the fifth century

AD

. As such, English is classified as a West Germanic language. This group includes modern language groups such as German, Frisian and Dutch, as distinct from North Germanic (Scandinavian) languages, Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Icelandic and Faroese, and East Germanic languages,

represented best by the now extinct Gothic, known from Biblical translations, but including also Vandalic, Burgundian and Lombardic (

Figure 8.1a

).

According to this classification, two thousand years ago, or possibly earlier, the West Germanic group underwent a distinct split, producing a new branch called High German, a group now spoken farther east by the majority of Germans, Austrians and Swiss. The change happened in the ancestor of Old High German, which underwent a systematic sound-shift differentiating it from the rest of the group, namely Low German (or Low Saxon), Dutch-Flemish (and its ancestor Low Franconian) and Frisian, which preserved the relevant ancestral West Germanic sound values.

Figure 8.1a

Conventional Germanic language tree. In the conventional reconstruction, based on sound changes, Old English arose around 1,500 years ago from an ‘Old German’ continental version of ‘Anglo-Saxon’. The latter groups with the main West Germanic branch of Germanic languages and sub-groups with the ‘Low Germanic’ variants now found on the North Sea coast. The closest of these to modern English, on this basis, is Frisian.

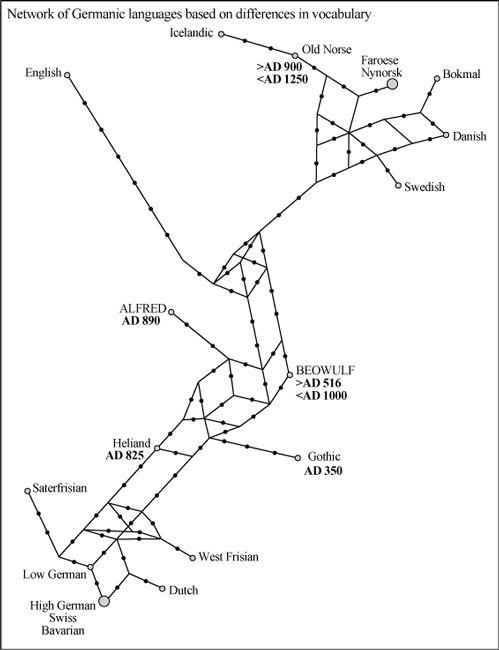

Figure 8.1b

Germanic vocabulary network suggests English as a fourth Germanic branch. Based on vocabulary similarity, Forster’s network groups all Continental West Germanic languages close to each other and relatively near to Old German (Heliand poem). However, Old English (Beowulf/Æfred) was already diverse, and as far from Old German as the latter is from Frisian – even beyond the Gothic branch. English appears to form a fourth branch splitting off closer to Scandinavian languages than the others.

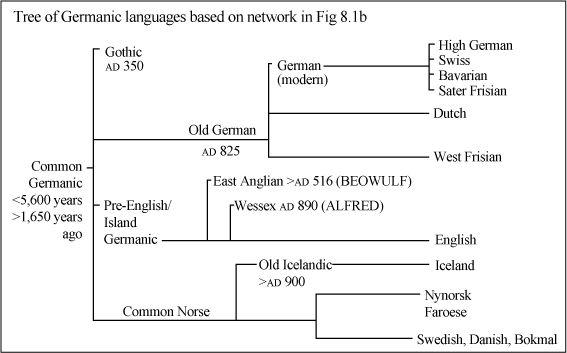

Figure 8.1c

Germanic tree four-branch reconstruction based on

Figure 8.1b.

When the Germanic network is viewed as a tree, there are four branches rather than the conventional three, with a new pre-English ‘Island Germanic’. Forster argues that the break-up of these four can be no younger than the Gothic Bible (

AD

350), and thus older than the ‘Anglo-Saxon invasion’, and possibly as much as 4,000 years old.

A second overlapping set of geographically based differences occur in West Germanic languages, the so-called coastal features, which can be shown to exist between Old English, Old Frisian and Old Saxon as a group on the one hand, and Old High German on the other. These coastal features are also sometimes used to invoke a language group variously described as North Sea Germanic or Ingvaeonic. The latter term, in spite of the misspelling, refers back to a classification by the first-century

AD

authors Pliny and Tacitus, who divided the West Germans into three groups: ‘the Ingaevones, dwelling next the ocean; the Herminones, in the middle country; and all the rest, Instaevones’.

1

‘Ingaevones’ thus referred to the tribes who lived along the coast from North Gaul to Denmark.

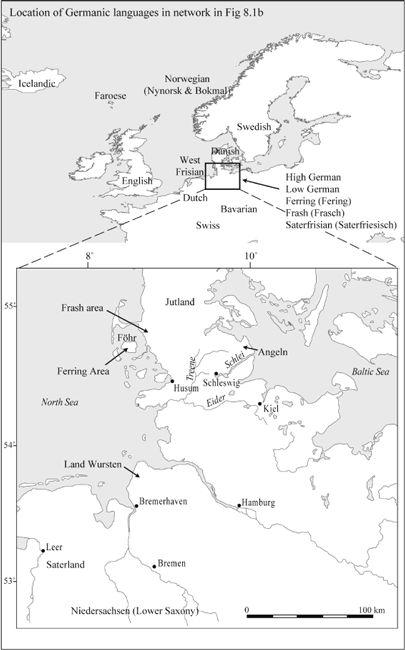

Figure 8.1d

Early historical locations of Germanic languages with the ‘Anglo-Saxon homeland’ enlarged. Ptolemy located the Saxones at the base of the Cimbrian Peninsula in ad 150 and confirmed older classical sources of the location of ‘Old Saxony’ far to the north-east of Lower Saxony.

The North Sea Germanic group contains several branches. Low German (known as Low Saxon in the Netherlands) is spoken on the North German Plain in Germany and the Netherlands. Frankish is now extinct, but was the language formerly spoken in northern or Belgic Gaul and the Low Countries, and is thought to have spread within the past two thousand years. Low Franconian, an approximate ancestor of Dutch-Flemish, was closely related to Frankish. Depending on exactly when Germanic languages first arrived in the Netherlands, there may even have been another Germanic language spoken by those Belgae with whom Caesar had so much trouble, and whom Hans Kuhn calls ‘The People between the Celts and the Germans’ (see p. 321). Frisian is a distinct contemporary group of languages spoken in the northern Netherlands and Germany. When the method of comparing systematic language changes is applied, Frisian, of all the Germanic languages – rather than Low Saxon – is found to be most closely related to English. This is surprising both from the point of view of the ‘Anglo-Saxon invasion’ and, as we shall see, the genetic evidence. The same structural proximity applies to Old Frisian and Old English (

Figure 8.1a

).

2

There are problems with these seemingly neat divisions into High and Low German languages and the simplistic view that Low German spawned English quite recently. Apart from the point that Old English should, on the evidence of Gildas and Bede, be more closely related to Low Saxon and/or Anglian

than to Frisian, English is actually surprisingly dissimilar from all its neighbours, whatever its elevation above the sea (high or low) or its structural position in the West Germanic language tree. This is the case whether one compares ancient with ancient or modern with modern.

Old English and Old Frisian both changed their treatment of vowels compared with other Low German languages such as Old Saxon. But by the time the first texts appeared in Old English, only a couple of hundred years after the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ invasion, there had apparently been further vowel shifts (changes), resulting in a dramatic reduction in the number of distinct endings (inflections) that could be added to words when compared with Germanic languages on the other side of the North Sea. Not only that, but the first texts in ‘Old English’ also differed markedly from one another, according to region, for there were three distinct dialects: Anglian, West Saxon and Kentish.

The reason for this apparently rapid divergence into dialects might be the different languages spoken by the founding groups. But the languages of the three putative Low German invaders, the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, were supposed to be very similar, if not the same, at the time of invasion. In any case, this still does not explain the rapid divergence of King Ælfred’s West Saxon or of Beowulf’s Anglian from contemporary Continental Low Saxon texts such as the ninth-century Old Low German epic poem

Heliand

.

3

An alternative explanation might be local hybridization with celtic or Latin, but as has already been pointed out, there is scant evidence for that.

The greatest differences between Old English and other North Sea Germanic languages, however, are in their vocabularies

rather than just their structural ancestry. Even Old Frisian, the ‘closest relative’ of Old English, shares five times more uniquely derived forms of words with German than with Old English.

4

If we now compare modern descendants of Germanic languages for shared cognate words, as the Hawaiian linguist Isidore Dyen did, English again turns out to be the odd one out. English branches off deeply compared with both the surviving West and North German (i.e. including Scandinavian) language branches.

5

This ancestral position of English with respect to its putative parent cannot be explained simply by the intrusion of a substantial minority of French words following the Norman invasion, since recent (unpublished) evidence also suggests a similar position of English when mathematical comparisons are made for syntactic features.

New Zealanders Russell Gray and Quentin Atkinson analysed the same data that Dyen had created, and confirmed the deep rooting of English in Germanic languages (

Figure 6.2a

). English linguistic-genetic researchers April and Robert McMahon have also addressed this question by re-analysing Dyen’s data using a number of different tree-building methods which again consistently put English as an early split.

6

They came up with a fascinating possible explanation – that there was significant under-detected borrowing from North Germanic (i.e. Scandinavian languages) at an early stage. Obvious borrowing of words such as the French loans can be adjusted for in analysis of relationships; but less obvious loanwords, such as those occurring between the main Germanic groups, can cause problems in tree-building. In their words,