The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (49 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

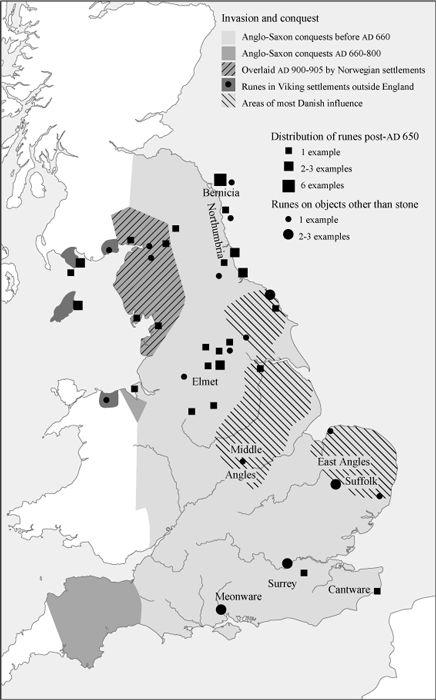

Figure 9.2b

Rune finds more recent than

AD

650 have a more complex type and distribution, being found away from the initial Anglian settlements in other Anglian sites in Mercia and Northumbria and in later Norwegian Viking settlements in the west. Anglo-Frisian style runes are now found, but Saxon areas are still nearly empty of datable runes in this later period.

There is only one curious exception to this tight eastern Anglo-Jutish runic distribution before 650. This is a single copper-alloy fitting belonging to a leather bag for a hanging scale-set, dating to the sixth century and found at Watchfield, west Oxfordshire. Watchfield is roughly halfway between the nearby Uffington White Horse and Badbury Hill, near Faringdon. The latter is one of several Badburys in western England which are candidates for the location of the famous sixth-century battle of Badon Hill. Watchfield would have been near the border between Wessex and the early independent Kingdom of the Hwicca between the Severn and the Avon. The Hwicca have been thought by some to represent continuity with the coin-making Dobunni of Roman times. The names of their royalty were, however, Saxon, according to Bede, who states that a West Saxon queen, ‘whose name was Ebba, had been christened in her own island, the province of the Wiccii’.

24

However, from a few ‘pagan’ burials and place-names, we know that there was a small early Anglian presence in Hwicca during the fifth and sixth

centuries.

25

As we shall see, this western scrap from Watchfield has a tantalizing bearing on the web of confusion about Saxons spun by Gildas.

One of Page’s other reasons for drawing a line between early and late English runes is found in details of their forms (orthography), which distinguish runes derived from North Germanic and West Germanic geographical and linguistic regions. Although runes were invented most probably in the North Germanic (i.e. Scandinavian) region, which, as far as this type of evidence is concerned, includes Jutland (in Denmark) and Angeln (in Schleswig-Holstein), they appear considerably later in the West Germanic Frankish, Allemanic and Frisian territories. In between these two runic regions are the parts of northern Germany/Lower Saxony that are thought by some to be the original homeland of the Saxons. These Continental Saxon areas are practically devoid of runes (

Figure 9.3

).

26

The earlier runes differ in their orthography from the later ones. For instance, the character for ‘H’ in Norse/Scandinavian runes shows a single-barred sloping crosspiece between the uprights ( ), while the later equivalent in the West-Germanic Frisian region has a double bar (

), while the later equivalent in the West-Germanic Frisian region has a double bar ( ). The early runes in England before 650 are single-barred (i.e. Norse), while the later forms are double-barred, as in Frisia (

). The early runes in England before 650 are single-barred (i.e. Norse), while the later forms are double-barred, as in Frisia (

Figures 9.2a

and

9.2b

). The double-barred variant could have had an English origin and then spread to Frisia, or a Frisian origin and then spread to England. Page prefers the first model, mainly on the clear basis of comparative dating. But surprisingly, this suggests an English influence on Frisia rather than the other way round.

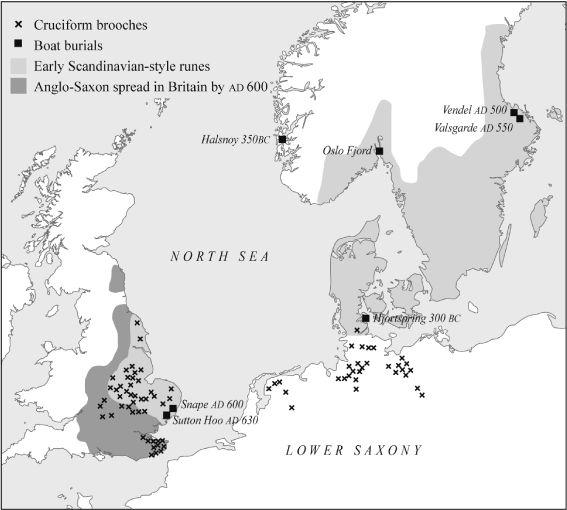

Figure 9.3

Multiple links of material culture, such as cruciform brooches, exist between the ‘Anglo-Saxon homelands’ at the base of the Danish Peninsula and Anglo-Jutish territories in England, but these do not extend to Lower Saxony. Early runes and boat burials, however, suggest more of a connection to southern Scandinavia and Angeln in Schleswig-Holstein.

Significantly, the single sixth-century western runic example from Watchfield mentioned above is of the Early Norse type. This copper-alloy fitting bears a runic text beginning

hariboki

… (

Figure 9.2a

). The H is of the Norse single-barred form ( ), and the first element

), and the first element

hari-

means ‘army’.

27

Given its date, location, lack of geographical association with Angles and proximity to several putative south-western Badon Hill battle-sites, we

might pause to speculate on the identity of the combatants in that symbolic last battle, which the Britons actually won.

As we have seen, where Gildas has the enemy implicitly as Saxons, Bede again demurs and prefers to call them ‘Anglians’ in his chapter title for the same event. There were probably plenty of Saxons in southern England in the sixth century, but the Roman record of the Saxon shore in the

Notitia dignitatum

could imply that they had resided there long before the battle. Resident Saxons in Wessex would hardly have constituted a pushover for Ambrosius Aurelius (or King Arthur, if that is who he was). The Anglians, on the other hand, had only a brief residence in the south-west in the fifth and sixth centuries evidenced by some graves and place-names. Their disappearance until later centuries is consistent with them being on the losing side in that particular conflict. It would, of course, be taking this particular rune-story too far to suggest that this copper bag fitting was a trophy or detritus of King Arthur’s great stand.

To oversimplify and summarize Page’s favoured explanation: runes originated in Denmark and spread from the North Germanic or Scandinavian region to eastern England in the fifth century (i.e. contemporary with Gildas’ and Bede’s invasion chronology), and then after 650 mutated to a modified form which appears to have spread across the North Sea to Frisia. This story of the runes gives no obvious support for Gildas’ story of Saxons being invited to England and landing on the east coast. But it is clearly consistent with Bede’s preferred version

of Anglian invitations and invasions in the east of England in the title of chapter 15 of his

Historia

. It fits with a Jutish cultural intrusion too, although Gildas does not mention the Jutes, and Bede, although he mentions all three groups, is less specific about the Jutes’ early role.

Almost more questions have been raised than answered so far by the map of earliest runes (

Figure 9.2a

). Looking at their source, the distribution of the earliest runes is exclusively southern Scandinavian, including Jutland and Angeln (for these locations see the map in

Figure 8.1d

). This in itself might suggest that the separation of language and culture between North and West Ger manic places not only Jutish but also Anglian in the North (Scandinavian/Norse) group rather than the West Germanic group; and that the split happened long before the ‘invasion’. Consistent with this is the fact that, although Anglian/Jutish runes were carried early over to England, they are absent from Saxon regions.

This Norse perspective has enormous implications for those parts of more northerly Old English we know least about from manuscript sources (namely Lindsey, western Northumbrian and East Anglian). In his summing-up, Page stresses the potential linguistic importance of runes: ‘In manuscript there is nothing so early by two or three centuries as the Caistor-by-Norwich [East Anglia] or Loveden Hill [Lindsey] texts [runes].’ He points out that we cannot be sure that the former was not Norse; in his opinion,

modern linguists appear ignorant of or nonchalant about this primary evidence. The Scandinavian affinities of these and of the Spong Hill [East Anglia] and Welbeck Hill [Lindsey] inscriptions

remind us that a rigid division into North and West Germanic language groups is outdated and unrealistic, and that we must reckon on the likelihood of some northern influence on the forms of Old English.

28

Much of the argument for all Old English dialects being part of the West Germanic group, rather than Norse, is based on much later texts, particularly the more abundant West Saxon ones in Roman script. We can ask whether the same linguistic division existed in Britain during the sixth century and earlier. Since there are no dated Wessex runes, no comparisons can be made with early Anglian runes. There is one tortuous clue to a linguistic division existing in the sixth century from the historian and commentator Procopius of Caesarea.

Writing at around the same time as Gildas, but from the other side of Europe in Asia Minor, Procopius was reliant on hearsay for information about the former western arm of the Roman Empire, so several of his garbled pieces of gossip about British geography and history are demonstrably inaccurate, and even internally inconsistent. One confusing text has always puzzled English historians, raising as it does the possibility of additional Frisian invasions of Britain, perhaps in the fifth century. Significantly, this snippet was said to have been obtained from some Angles who were part of a Frankish delegation to Constantinople (c.553):