The Other Slavery (6 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

During those five years, however, the monarchs’ reluctance to enslave Natives intensified. In particular, Queen Isabella emerged as an early champion of Indian rights. As Columbus kept insisting on his plans of enslavement and his men continued to ship Indian slaves in one guise or another, Isabella became exasperated. All along she had been extremely supportive of the Admiral. But by 1499, when she learned of the arrival of yet more Indians, she famously exploded: “Who is this Columbus who dares to give out my vassals as slaves?” Isabella and Ferdinand freed many Indians and, astonishingly, mandated that many of them be returned to the New World. We know that in the summer of 1500, a group of Indians was asked whether they wanted to go back. With the exception of one old man who was too sick to travel and a little girl who wished to remain in Spain, all of the others chose to make the perilous voyage to the Caribbean.

25

The opposition of the Catholic monarchs was a serious blow to Columbus’s plans for a transatlantic Indian slave trade. But the most important limiting factor was the economic development of the Caribbean. European colonists slowly realized that the lush archipelago was nowhere near the East or the Spice Islands but nonetheless possessed valuable natural resources. To extract these riches, many laborers were needed. Columbus himself explained it better than anyone else in a

memorial

(historical account) in which he reflected on his lifelong accomplishments. He wrote that he “would have sent many Indians to Castile, and they would have been sold, and they would have become instructed in our Holy Faith and our customs, and then they would have returned to their lands to teach the others.” Yet according to the Admiral, they stayed in the Caribbean because “the Indians of Española were and are

the greatest wealth of the island,

because they are the ones who dig, and harvest, and collect the bread and other supplies, and gather the gold from the mines, and do all the work of men and beasts alike.”

26

The Greatest Wealth

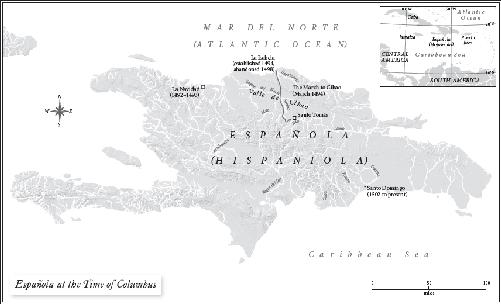

The Spaniards did not so much discover the gold of Española as they were led to it by the Indians. The colonists saw the Natives of the north coast wearing shiny “leaves” dangling from their earlobes and nostrils. The islanders were in the habit of picking up small pieces of gold and beating them into thin strips or leaves. Using signs, the visitors questioned the Natives about where they had procured this gold, to which

they responded in kind by pointing to the mountainous interior and saying “Cibao.”

27

Columbus dispatched a group of some thirty men under the command of Alonso de Ojeda, a “young and courageous nobleman” (and future slaver), into the promising mountains. Indian guides gladly led the way. From the coastal plain, the party ascended a mountain range that gave way to a broad interior valley and then a second range (the Cordillera Central), which was Cibao proper. Large rivers crisscrossed the foothills of this range. The indigenous escorts were the first to demonstrate how to collect the gold. “They dug a hole in the river sand about the depth of an arm, merely scooping the sand out of this trough with the right and left hands,” wrote one chronicler, “and then they extracted the grains of gold, which they afterwards presented to the Spaniards.” The chronicler, Pietro Martire d’Anghiera (Peter Martyr), an Italian nobleman attached to the Spanish court, remarked that many of the grains were the size of peas or garbanzo beans and affirmed that in Old Castile he had seen an ingot procured by Ojeda that was “as large as a man’s fist . . . and to my great admiration I handled it and tested its weight.” The Indians evidently placed some value on gold and used it to make ornaments. But the interest shown by the strangers was on a different scale altogether. Gold seemed to be an obsession with them.

28

The young nobleman Ojeda reported that in two weeks, he had found more than fifty streams and rivers that contained gold and that the gold-bearing places were so numerous “that a man could not name them all.” An elated Columbus investigated for himself. Wishing to impress the Indians, he organized a second and much larger group, consisting of “all the gentlemen and about four hundred foot soldiers.” Proceeding in military formation, these men carried banners and upon their approach to Indian villages fired guns and blew trumpet fanfares. We can only guess what the people of Cibao thought of these theatrics. The martial display must have worked on some level, because the Natives received the strangers “as though they had come from the sky.”

29

The Spaniards had come to stay. They chose a promontory by a riverbank to build a fortified post they called Santo Tomás, because just like the doubting saint, they had to see in order to believe. This was the first

of a number of fortifications, smelters, mining camps, and placer operations built throughout the foothills and interior valley in the next few years. By 1496 the settlers were firmly in control of Cibao, and by the turn of the sixteenth century the gold region of Española had already become the mainstay of the Spanish presence in the New World.

Gold was not the only valuable product on the island. Española was a gateway and resupply center for expeditions bound for other parts of the New World. Entrepreneurial colonists made money by selling pigs or cattle to the passing ships. Other Europeans came to control the trade in dyewood collected on the southwest coast and the pearls arriving from Venezuela. Still others found their fortune in sugarcane, operating the very first sugar plantations in the New World. More than any other enterprise, however, the gold mines determined the economy of Española and the entire archipelago and dictated how the Spaniards went about procuring labor.

30

The goldfields of Cibao were not the most dangerous places for the Indians to work. For sheer horror and attrition rates, the “pearl coast” was worse. Indian divers there spent agonizing days making repeated descents of up to fifty feet, while holding their breath for a minute or more. Few Natives could endure these brutal conditions for long. Although the goldfields of Cibao were not as lethal, they affected the largest number of Indians in the entire circum-Caribbean region. Looking at the placid environment of modern Cibao, one cannot imagine that it was once the pulsating heart of the colonial enterprise. Today there are ranches and green pastures with lazy cows, humble houses where ordinary people struggle to make ends meet, and scenic spots where wealthy Dominicans have built their vacation homes. But five hundred years ago, it was the site of the first gold rush in the Americas.

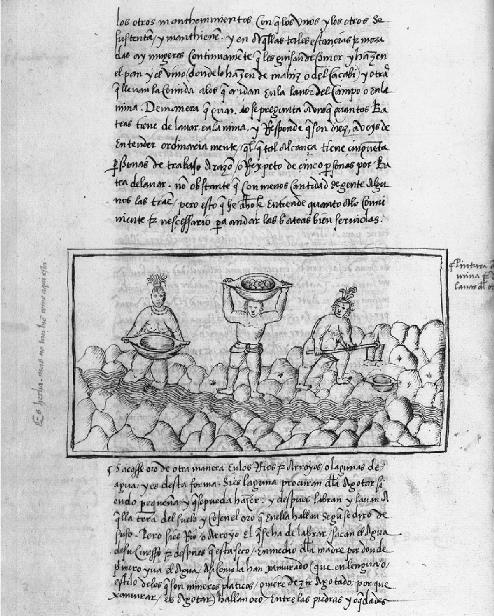

This contemporary drawing captures the three tasks involved in panning for gold. Though crude, the tools shown here were quite effective and are still used by present-day gold seekers.

Columbus’s initial attempt to squeeze the gold out of Española consisted simply of requesting that all the Indians of Cibao who were fourteen years of age or older provide enough gold dust to fill a hawkbell—a few grams—as tribute every three months. (Hawkbells, used in falconry in Europe, were brought to the New World as trade goods.) “All prudent and learned readers will immediately recognize the justice of this tribute, and the violence, fear, and death that its imposition necessitated,” warned Bartolomé de Las Casas. Although some caciques (chiefs) made halfhearted efforts to meet the Spanish quota, this method of obtaining gold failed completely. Most Indians did everything they could to avoid the tribute, including hiding away in the mountains or fleeing Cibao altogether. After three collection periods, the Indians had provided only 200 pesos’ worth of gold out of an anticipated 60,000. Clearly, if the Spaniards wanted gold from Española, they would have to get it themselves.

31

Spanish miners and prospectors flocked to the streams, savannas, and mountains of Cibao. Although flecks of gold could be found all over the region, only certain areas contained enough gold to make extraction profitable. An early colonist, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, tried his hand at gold panning and left the most detailed portrayal of these activities.

32

Each Spaniard arrived with his

cuadrilla,

or team of Indians. In most cases, the “miner” was merely a colonist with no knowledge of metals or mining techniques. Once he settled on a place—probably chosen after a mixture of hearsay, intuition, and preliminary digging and sampling—he had his Indians clear a square trench of about eight by eight feet. Sandy beaches along the rivers were ideal, but many alluvial placers were in wooded areas, known as

arcabucos,

or along hillsides that required the removal of large rocks and trees. Once the Indians completed this preparatory work, they dug the cleared area to a depth of about twice the length of a worker’s palm setting aside the removed sand and earth. They dug with simple tools, even with sticks and their bare hands in the early years. This was strenuous labor, but easier than the next step.

The same “digging” Indians or other members of the cuadrilla transported the piles of dirt to the nearest stream. An average-size trench produced more than six thousand pounds of dirt mixed with the tiniest fragments of gold. The Indians carried this dirt on their bare backs, in loads weighing three to four

arrobas,

about sixty to ninety pounds. These were very heavy burdens considering the slender build of most of the bearers. The work proceeded ceaselessly all day. Instead of using valuable beasts of burden, the Spaniards compelled Natives to do all the hauling; horses and mules were devoted to the tasks of conquest and pacification. The Indians were even forced to carry their Christian masters in hammocks. As a result, they developed “huge sores on their shoulders and backs as happens with animals made to carry excessive loads,” commented Friar Las Casas, who arrived in Española right at the

time of the gold rush, “and this is not to mention the floggings, beatings, thrashings, punches, curses, and countless other vexations and cruelties to which they were routinely subjected and to which no chronicle could ever do justice.”

By the water, a third group of “washing” Indians—usually women, because this work was less physical—received the cargo. Standing in the stream with the water up to her knees, each woman held a large wooden pan called a

batea.

“She grabs the

batea

by its two handles,” wrote Oviedo, “and moves it from one side to the other with great skill and art, allowing just enough water to rush in as the earth dissolves and the sand is washed away.” With some luck, after sifting thousands of pounds of earth, the woman would find “whatever God wishes to give in a day”—a few grains of gold—in the bottom of the

batea.

33

Each cuadrilla consisted of at most a few dozen laborers. The smallest had only five: two diggers, two carriers, and one washer. Yet put together, all these teams made Cibao a veritable anthill. In promising areas, the competition was fierce. When a miner struck gold, others immediately flocked there. To prevent rivals from setting up next to him, he would “invite someone whom he wishes to help and chooses as a neighbor” to move in first. Even though Columbus and his family attempted to limit the number of Spaniards going to the gold region, the number of cuadrillas grew steadily in the late 1490s and early 1500s. During the first decade of the sixteenth century, the heyday of gold production in Española, the island may have yielded around two thousand pounds of gold per year. It is possible to imagine an enormous ingot of that weight, but it is much harder to comprehend the madness of some of the Spanish owners—one of whom became notorious for throwing parties in which the saltshakers were full of gold dust—or to grasp the suffering of some three or four thousand able-bodied Indians—perhaps as many as ten thousand—toiling daily in the gold mines of Cibao to make such opulence possible for the colonists.

34