The Oxford History of the Biblical World (38 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

To the sound of musicians at the watering places,

there they repeat the triumphs of Yahweh,

the triumphs of his peasantry in Israel.

Another recurring theme in this archaic poetry is the bond between Israel and Yahweh. Other peoples have other gods, but Yahweh is Israel’s god, as in Deuteronomy 32.8-9; they must recognize and proclaim this, and he will protect them and fight for them, and secure for them a fertile resting place:

There is none like God, O Jeshurun [a name for Israel],

who rides through the heavens to your help,

majestic through the skies.

He subdues the ancient gods,

shatters the forces of old;

he drove out the enemy before you,

and said, “Destroy!”

So Israel lives in safety,

untroubled is Jacob’s abode

in a land of grain and wine,

where the heavens drop down dew.

Happy are you, O Israel! Who is like you,

a people saved by Yahweh,

the shield of your help,

and the sword of your triumph!

Your enemies shall come fawning to you,

and you shall tread on their backs.

(Deut. 33.26-29; see also Exod. 15.2, 11, 13, 17; Judg. 5.3)

The makeup and structure of Israel in the premonarchic era are also treated in the oldest poetry, and for the purpose of tracing these early pictures of Israel we will add some of the prose of the books of Joshua and Judges. Three of our four earliest poems count off names of tribes and have something to say about each. The number and names of tribes included are different in each case, and only Genesis 49 uses the canonical list known from the birth stories in Genesis 29-35.

In Judges 5.14-18, each tribe mentioned is judged according to whether it came to the battle or preferred to sit it out. Only ten tribes are named. This earliest list of Israel’s constituent tribes includes Ephraim and Machir (for Manasseh) rather than Joseph; Simeon and Levi are nowhere mentioned (see Gen. 34; Levi is rarely mentioned as a landed tribe, outside idealized pictures in Genesis, the conquest and settlement narratives in Joshua and Judges, and later in Ezekiel and Chronicles); and the southern tribe of Judah does not yet seem to be a part of Israel. The blessings in Deuteronomy 33 and Genesis 49 have still different lists of tribes. Deuteronomy 33 is missing only Simeon from the canonical twelve, and only Genesis 49 includes them all.

The allotments of tribal land in Joshua 13-19 reflect the earliest listing we have that gives territories either settled in or claimed by twelve landed tribes, that is, by the canonical twelve with the exception of Levi and with the split of Joseph into Ephraim and Manasseh. This enumeration reflects the tribal territories or claims at a time when Judah has joined the confederation.

The Deuteronomic introduction to the period in Judges 1 exhibits still another roster: Simeon is something of an afterthought, almost absorbed into Judah (see already Josh. 19.1, 9); Issachar has disappeared, its territory taken up by Manasseh; Benjamin is not doing well finding territory for itself, nor is Dan, who will later remove to the far north of the land. The Transjordanian tribes are not mentioned, but Judges 1 is about the “conquest” of the area west of the Jordan River, and in this scheme the Transjordanian tribes had already been settled during Joshua’s time.

Reuben disappears from other fairly early sources, like David’s census in 2 Samuel 24 and the ninth-century Mesha Stela from Moab, and that same stela places Gadites in what was once Reubenite territory. Reuben’s stature as firstborn in the Genesis sources and in Deuteronomy 33 must reflect an early preeminence, preceding a subsequent rapid decline and disappearance. That preeminence might have depended on an early shrine: Joshua 22 implies such a shrine in Transjordan, and the Mesha Stela mentions a religious center at Nebo, in what was once Reubenite territory. We have also seen in our sketch of the religious beliefs exhibited in the early poetry (and supported by Exod. 3) the tradition that Yahweh himself originated in, or at any rate marched from, the land to the southeast of Israel; Reuben’s territory would have been the closest early Israelite soil that such a march would have encountered.

The nature of the evidence makes it impossible to determine with certainty the makeup of Israel at any point in the period of the judges, but a few elements are dependable, from both literary and archaeological evidence. Archaeology suggests that the central hill country of Ephraim, Manasseh, and Benjamin was the core of early settlement, with occupation of parts of Naphtali, Zebulun, and Asher coming either contemporaneously or soon after. These results accord with the picture presented

in Judges 4-6, although it is not yet clear what the status of Issachar was in the earliest settlement. Moreover, the book of Judges reports various assortments of northern tribes capable of concerted effort—Zebulun and Naphtali in Judges 4; Ephraim, Benjamin, Manasseh, Zebulun, Naphtali, and Issachar in Judges 5; Manasseh, Asher, Zebulun, and Naphtali in Judges 6, with Ephraim also volunteering. These are precisely the areas at the center of Israel’s earliest existence. With the exception of the Deuteronomic frame and the model story of Othniel in Judges 3.7-11, Judah (and its subgroup Simeon) is largely missing from the stories of the early judges, and this, too, is not surprising since Judah was apparently settled late in the premonarchic era. Judah is prominent in the stories set at the end of the period: the Samson stories; several times in Judges 17-21; 1 Samuel 11.8 and 15.4, where Judah is listed separately from Israel; and in the stories of David. There is as yet no way to tie the settlement west of the Jordan River to that in Transjordan, and at the same time to observe ethnic differences between later Israelite Transjordan and later Moabite or Ammonite Transjordan. Whether any of these assortments of tribes argues for smaller, pre-Israel confederations is impossible to say, except to exclude the far southern tribes (Judah and Simeon) from the earliest conception of Israel and to note that Dan was never securely enough situated in the south to be of much help to its Israelite neighbors.

What then was the earliest confederation that was called “Israel”? Perhaps it comprised Benjamin, Ephraim, Manasseh, Naphtali, Zebulun, and Asher (and possibly Issachar); and perhaps it also encompassed the southern Transjordanian area north of the Arnon (thus Gad, and Reuben as long as it existed). Such an answer, however, begs several questions: whether a tribal Israel existed prior to the Iron I settlement of the central highlands and similar areas in Transjordan; whether the people in what became Israel can be separated from the other Iron I tribal societies that sprang up at the same time and in the same way, such as Moab and Edom; whether those who settled the eastern side of the Jordan were tied to Israel in Iron I, or to Moab, or to neither. In other words, did the people who moved into these marginal areas in Iron I already conceive of themselves as tribal confederations, with names and languages that tied some of the tribal groups together into larger entities (say, Israel or Moab, speaking Hebrew and Moabite) and at the same time separating those larger groups from each other? Or were they agriculturalists and pastoralists looking for free land in which to make their living—the withdrawal of Egyptian power at the end of the Late Bronze Age having opened up such possibilities, with structure at the tribal and larger levels coming only after they had settled in their new niches?

The southern Transjordanian area shares its material culture with the settlements west of the Jordan, but it also does with Moab, for instance. So there is no archaeological way to tie the southern Transjordanian areas exclusively with the area west of the Jordan in Iron I. By the ninth century

BCE

, the Mesha Stela assigns the area in question to the Gadites, but we cannot prove that a tribe Gad (much less Reuben) held this territory in Iron I, or that whoever held the territory was related by covenant to contemporaneous settlements west of the Jordan. The languages and dialects of the entire area in question were close enough to each other to have been mutually understandable.

The idea of a covenant or a confederation of tribes bound to each other and to a

particular deity by treaty/covenant is not something archaeology can test, whether the question be about “Israelites” east and west of the Jordan River or about the hill country and Galilean settlements. We do know, however, that settlement of the central hill country west of the Jordan and the southern valley east of the Jordan began to flourish at about the same time at the beginning of the Iron Age, that they were part of later Israel, and that they were remembered as forming coalitions for defense based on their common adherence to the religion of Yahweh.

Bloch-Smith, Elizabeth.

Judahite Burial Practices and Beliefs about the Dead.

JSOT/ASOR Monograph Series, 7; JSOT Supplement, 123. Sheffield, England: JSOT, 1992. Archaeological survey covering 1200-586

BCE

, describing types of burials and grave goods, as well as a discussion of the biblical material.

Boling, Robert G.

Judges.

Anchor Bible, vol. 6A. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1969. A standard commentary, with archaeological information.

Callaway, Joseph A. “The Settlement in Canaan: The Period of the Judges.” In

Ancient Israel: A Short History from Abraham to the Roman Destruction of the Temple,

ed. Hershel Shanks, 53-84. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1988. An accessible summary of archaeological evidence of conquest and settlement and of scholarly controversy about the evidence.

Campbell, Edward F., Jr.

Ruth.

Anchor Bible, vol. 7. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1975. A commentary stressing literary issues, with much archaeological and ecological detail.

Cross, Frank Moore.

Conversations with a Biblical Scholar.

Ed. Hershel Shanks. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1994. An informal exposition of wide-ranging views from the dean of American biblical scholars.

Dothan, Trude, and Moshe Dothan.

People of the Sea.

New York: Macmillan, 1992. A popular and well-illustrated summary of Philistine history and culture.

Finkelstein, Israel.

The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement.

Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1988. A technical exposition of the results of recent archaeological surveys in the central hill country, with conclusions drawn about Israel’s earliest settlement.

Freedman, David Noel.

Pottery, Poetry, and Prophecy: Collected Essays on Hebrew Poetry.

Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1980. Several of the essays in this collection focus on what the earliest biblical poetry tells us about Israel’s history and religion in the early Iron Age.

Frick, Frank S.

The Formation of the State in Ancient Israel.

The Social World of Biblical Antiquity Series, no. 4. Sheffield, England: Almond, 1985. A comparative social-scientific discussion of the stages in moving from a segmentary society to a centralized state.

Hackett, Jo Ann. “1 and 2 Samuel.” In

The Women’s Bible Commentary,

ed. Carol A. Newsom and Sharon Ringe, 85-95. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster/John Knox, 1992. A consideration and explanation of the various women’s roles and gender issues in the books of Samuel, including a discussion of method.

McCarter, P. Kyle, Jr.

I Samuel.

Anchor Bible, vol. 8. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1980. A sound and readable commentary stressing historical and text-critical issues.

Naveh, Joseph.

Early History of the Alphabet.

Jerusalem: Magnes, 1987. A survey of the earliest alphabetic inscriptions and of the later evolution of the script traditions.

Seow, Choon-Leong. “Ark of the Covenant.” In

Anchor Bible Dictionary,

ed. David Noel Freedman, 1.386-93. New York: Doubleday, 1992. A concise and complete discussion of the history and literary uses of the ark.

Stager, Lawrence E. “The Song of Deborah: Why Some Tribes Answered the Call and Others Did Not.”

Biblical Archaeology Review

15, no. 1 (January-February 1989): 51-64. A study of Judges 5 utilizing linguistic and archaeological evidence, especially settlement patterns.

Wilson, Robert R.

Sociological Approaches to the Old Testament.

Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984. A short, informative introduction, including test cases.

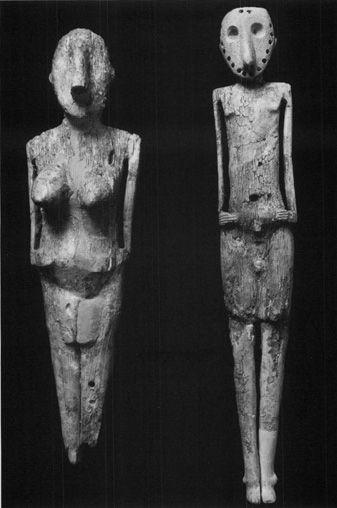

Ivory figurines from the Beer-sheba region dating to the late Chalcolithic period (early fourth millennium

BCE

). The male figure on the right is about 33 centimeters (13 inches high); the perforations on his head were probably for attaching hair. Figurines like these may have been used in domestic or communal fertility rituals. (© The Israel Museum, Jerusalem)