The Parthenon Enigma (34 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

I would argue that the girl’s nudity is not accidental. Her garment is open to communicate that she is in the process of changing clothes. Removing her everyday attire, our heroine is about to put on her funerary dress, a great winding sheet that she and her father hold up for all to see. Through a pictorial device known as “

simultaneous narrative,” the artist compresses present and future events into a single image.

84

We see the dressing ritual of the present and anticipate the

virgin sacrifice that is to follow moments later, its imminence betokened by the shroud.

In the Greek world, young women who died before marriage were buried in their wedding dresses.

85

Therefore, in Greek tragedy, we find maidens headed for

death changing, in advance, into their bridal/funerary robes. In the

Trojan Women

, Euripides presents the princess-prophetess

Kassandra as she is taken from Troy, dressed as a bride for Agamemnon.

86

In fact, Kassandra is dressing for her murder at the hands of Klytaimnestra. So, too, in

Iphigeneia at Aulis

, Euripides presents his heroine all decked out in her wedding finery (

kosmos

), complete with a bridal crown (

stephane

), as she prepares for what she thinks will be her marriage to Achilles.

87

Actually, of course, Iphigeneia is going to her death.

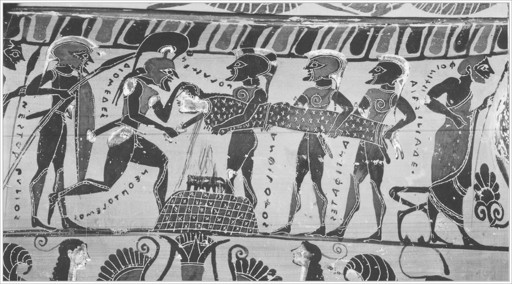

Polyxena sacrificed by Neoptolemos at tomb of Achilles near Troy. Tyrrhenian amphora by the Timiades Painter, ca. 570–560 B.C. (illustration credit

ill.57

)

Some skeptics view the folded fabric in the so-called peplos scene as being too large for the funerary dress of a sacrificial maiden. But throughout Greek tragedy special emphasis is placed on the voluminousness of the garments worn by virgins as they go to sacrifice. Viewed as an expansive winding sheet, the cloth displayed on the Parthenon frieze is entirely appropriate for dressing the little Erechtheid. In

Aeschylus’s

Agamemnon

,

Iphigeneia is described as being “wrapped round in her robes” as her father leads her to the

altar.

88

The word used here is

peploisi

, the plural of

peplos

, suggesting several fabrics wrapped entirely around Iphigeneia. Before the maiden Makaria is killed in Euripides’s

Children of Herakles

, she asks her father’s companion

Iolaos to veil her with

peploi

,

89

likewise indicating a plurality of veils. Little remains of a lost play by Sophokles called

Polyxena

that dramatized the sacrifice of King Priam’s youngest daughter at the tomb of Achilles. Nonetheless, a surviving fragment refers to Polyxena’s “endless” or “all enveloping”

tunic (

chiton apeiros

), further attesting that the draping of the maiden as she is led to be killed is no small matter.

90

The violence

of Polyxena’s death is explicitly portrayed on a sixth-century

B.C.

amphora in London (previous page).

91

The princess of Troy is held horizontally high above the altar just the way an animal is raised as it is sacrificed.

92

Achilles’s son, Neoptolemos, slits Polyxena’s throat. Great streams of blood burst forth. Most distinctive here is Polyxena’s costume. Her arms are wrapped inside what is truly an “all enveloping” garment, a vast winding sheet woven with elaborate patterned decorations. Polyxena is already fully enfolded in her shroud as her neck is cut.

On the central panel of the Parthenon’s east frieze, the young daughter of Erechtheus, just like Polyxena,

Iphigeneia, and Makaria, must be veiled in voluminous fabric as she goes to her death. Just as one decorated a sacrificial animal, wrapping ribbons around its horns, so, too, one dresses up a virgin for sacrifice, draping her in beautifully woven garments evocative of bridal costume.

I maintain that the central image of the east frieze should be read as a dressing scene, a

kosmos

, or adornment of the maiden, just prior to sacrifice. The fact that we are shown a moment prior to the bloody climax is in keeping with the conventions of Greek art of the high classical period. We should not expect to see the altar of sacrifice, the knife that will slit the throat, or any of the blood and gore so obvious as in Archaic depictions of virgin sacrifice.

93

Images like that on the Polyxena vase are out of fashion by the 430s

B.C.

So, too, is the scene depicted on a white-ground

lekythos in Palermo showing

Agamemnon leading Iphigeneia to the sacrificial altar.

94

To be sure, the knife is shown in Agamemnon’s hand. But this vase predates the Parthenon frieze by sixty years, reflecting an Archaic taste for the gruesome detail of the culminating act. By the time the Parthenon frieze is carved in the 430s, the approach is more sophisticated, favoring anticipatory tension over graphic violence.

Still, it must be said that there are few surviving representations of

human sacrifice in Greek art before the fourth century

B.C.

It is an extraordinary subject, confined to extraordinary contexts. One can hardly speak of established conventions for it in Greek art. One of the reasons that the “peplos scene” has remained such a puzzle is that it shows an uncommon event for which no standard

iconography exists.

95

Both in visual and in dramatic arts, the high classical period saw

tastes move away from earlier preference for the explicit, favoring the subtler pleasure of expectation over the high drama of execution. The vogue for understatement can be seen in the famous statue of a discus thrower, the

Diskobolos

, attributed to the sculptor Myron and dated to the middle of the fifth century

B.C

.

96

In the many copies of this work, we see the nude athlete crouching, rotating, and lifting the discus high behind him. Tightly wound like a spring about to be released, the athlete is captured in a split second of maximum potential prior to the

kinetic burst of hurling the discus. Myron became so associated with this “pregnant” instant before the climax that we speak today of the “

Myronic moment” when describing statuary of the period. Similarly, in classical Greek drama, climactic death scenes are never shown onstage but, instead, are recounted to the audience by messengers.

This same principle can be seen in the

east pediment of the temple of Zeus at Olympia (

this page

). Without

Pausanias’s description of the central scene as the preparation for the chariot race of

Pelops and Oinomaos, we might never guess who was who among the dignified and somber figures. Would we catch the subtle reference to the impending action, hinted at in the crouching figure of the untrustworthy groom tampering with the chariot wheel?

97

A tragedy is about to occur: Pelops will cheat in the chariot race, and

King Oinomaos will be killed. The Parthenon’s east frieze, like the east pediment at Olympia, shows the local founding family in its own “pregnant” moment solemnly preparing for the awful outcome.

These iconic images of the founding families of Athens and Olympia were created exclusively for their respective contexts: the primary temples of each sanctuary. Neither the family group on the Parthenon’s east frieze nor the family group on the Olympia east pediment has iconographic parallels in vase painting or sculpture. Nor would any clues to their subjects have been needed at the time. Greeks at Olympia would have not only recognized but expected to see a reference to the local foundation myth in the place of prominence on Zeus’s temple. So, too, would the Athenians have instantly recognized the royal house of

Erechtheus. Indeed, Greeks on the whole were accustomed to the depiction of prominent families, both heroic and divine, in their visual culture.

98

But the impulse to connect the general population to the first family was nowhere more spiritually urgent or politically motivated than at Athens. To see the Erechtheids at the center of this central sculpture of the preeminent temple itself represents a kind of culmination, that of the larger program of genealogical narrative we have seen at work on the Acropolis since the Archaic period. It is also a culmination of that narrative’s societal function.

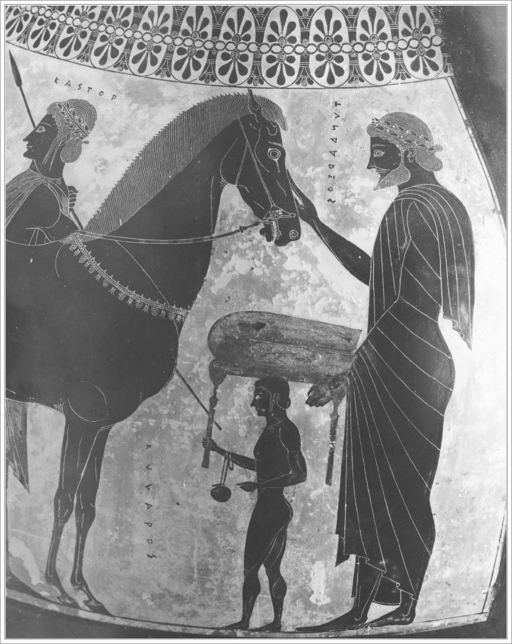

Serving boy bringing clean clothes to Kastor and Polydeukes; at right, their father, King Tydareos. Amphora, by Exekias, ca. 540 B.C. (illustration credit

ill.58

)

The two older girls at the far left of the panel have never fit comfortably into the historical reading of the scene (

this page

). While many scholars have identified them as the two

arrephoroi

who figured so importantly in the

rituals of Athena,

99

the pair are clearly too old to fill a post reserved for seven- to eleven-year-old girls. Their costumes, a tunic (

chiton

) beneath a mantle (

himation

), are the standard dress for adult women, not prepubescent girls, who regularly wore the peplos. Costume is an important indicator of age and here precludes the possibility that these young women could be

arrephoroi

.

100

Upon their heads, the maidens carry what appear to be cushioned stools. It is imagined that these are for the two adult figures, the “priestess of Athena” and the “priest of Poseidon-Erechtheus,” to sit on.

101

Some believe that these “sacred officials” are destined to join the assembly of divinities shown to either side of the central panel. Already in 1893,

Adolf Furtwängler expressed the opinion that the priest and the priestess are about to sit down to share a sacred meal with the gods, the so-called

Theoxenia (

this page

).

102

But this reading poses problems. Can

historical individuals join a group of invisible immortals?

103

And why should the priest and priestess have cushioned

stools when all but two of the gods (

Dionysos and

Artemis) do not?

Sometimes a stool is not just a stool. In the Greek world, it was used not only for sitting but also for transporting clean clothes, especially precious garments not to be sullied by unnecessary handling, elaborately woven fabrics that were enormously expensive, representing countless hours of labor at the loom. Images from vase painting regularly show such finery carried on stools. A black-figured amphora by

Exekias presents a serving boy bearing clean clothes on a stool carried upon his head (facing page).

104

These are intended for the twins

Kastor and

Polydeukes, young princes of Sparta (brothers of Helen), who arrive at the left of the scene. The little servant also carries a jar of oil, suspended from his wrist, a further signal that the twins are about to wash, perfume themselves, and change. The fabric on the stool appears rounded from the front, where it is folded over, and squared off from behind, where we see its opened ends. Were we to view the boy head-on, the bundle would appear rounded and cushion-like, just like that carried by the girls on the Parthenon frieze.

A red-figured jug in the

Metropolitan Museum of Art presents two women perfuming richly woven fabrics on a swinging stool suspended

above a fire (previous page).

105

One bends down to pour fragrant oil on the embers while the other tends the clothing. Here, as on the

Exekias vase, we see bundles of fabric representing not seat cushions but folded garments. In its original state, the Parthenon frieze would have been painted, and lively details of the fabric, its woven decoration, creases, and folds, would have made its identity clear.