The Parthenon Enigma (30 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

Vernon didn’t linger long in London. By June 1675, he was on the move to Venice and then to Greece, disembarking on Zakynthos with Eastcourt. The pair had decided to break off from their traveling party bound for Constantinople and to journey instead around the Greek Peloponnese and on to Athens where they stayed a few months.

6

In September, they crossed to the north side of the Gulf of Corinth, where Eastcourt fell ill and died. Vernon returned to Athens, where he stayed until late that year, copying inscriptions and examining architectural monuments. In all, he visited the Acropolis three times with the express purpose of measuring the Parthenon.

7

Vernon’s calculations have proven to be remarkably accurate. Especially significant is his measurement of the width of the interior room, or cella, at the east end of the temple, where others would reckon only the size of the exterior colonnade. Just twelve years later, Venetian cannons would blow the interior of the Parthenon to bits, and the original dimensions of the room Vernon had taken such care to measure would be lost but for him. Fortunately, he had recorded his findings in his personal diary as well as in a letter to Oldenburg posted from Smyrna on January 10, 1676, before setting off for his fateful rendezvous in Isfahan.

8

Vernon was the first to see in the Parthenon frieze animals brought to sacrifice followed by a triumphant procession. Somehow, he found time to look up from his calculations to describe the “very curious sculptures” (facing page) in the letter he posted from Smyrna.

9

And in writing of the south frieze in his diary entry for August 26, 1675, Vernon notes, “Men to west end on horseback people in triumphant/Chariotts.” His entry for November 8 describes a procession showing “Severall Bullockes with people conducting them to Sacrifice.”

10

Vernon’s field notes having been lost at sea, his personal diary and the letter to Oldenburg preserve his only surviving observations on what he calls the “Temple of Minerva.” The building “will always bear witness that the ancient Athenians were a magnificent and ingenious people,” he writes. Vernon didn’t leave Athens without making his own mark. To this day, one can see “Francis Vernon” carved on a block on the south wall of the Theseion, a temple that has been since ascribed to Hephaistos, in the Athenian Agora.

11

This inscription includes the date, 1675, as well as the names of his companions, Eastcourt and Bernard Randolph.

12

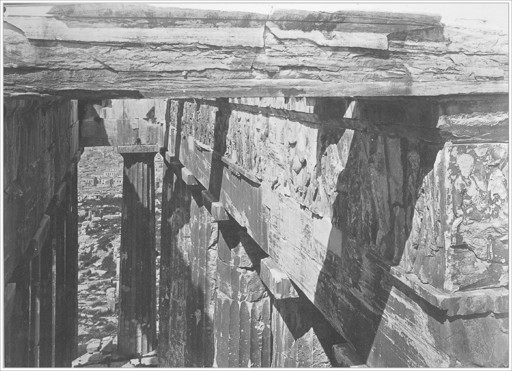

West portico of Parthenon. William J. Stillman, from albumen silver print, 1882. (illustration credit

ill.45

)

Precious few commentaries on the

Parthenon sculptures between antiquity and the seventeenth century survive, making Vernon’s observations all the more significant. That he takes a careful look at the long “ribbon”

13

of figured relief that wrapped around the interior of the Parthenon’s colonnade is not surprising: the exquisiteness of its carving, the classic lines and features of its human figures, the sensitive modeling of the drapery over flesh—all these aspects have led to the recognition of “Parthenonian style” as the highest standard for Western perceptions of beauty. But that he should have beheld in those lovely figures something that succeeding centuries of commentaries have failed (or been reluctant) to perceive, that it shows a

triumphant

sacrificial procession, may be the ultimate tribute to this remarkable man’s powers of seeing.

14

THE EARLIEST SURVIVING EXPLANATION

of the

Parthenon sculptures dates a full six hundred years after the temple was built. In his

Description of Greece

, the traveler

Pausanias, who visited the Acropolis in the second century

A.D.

, identifies the subject matter of the east pediment as the

birth of Athena, and Athena’s contest with

Poseidon as that on the west.

15

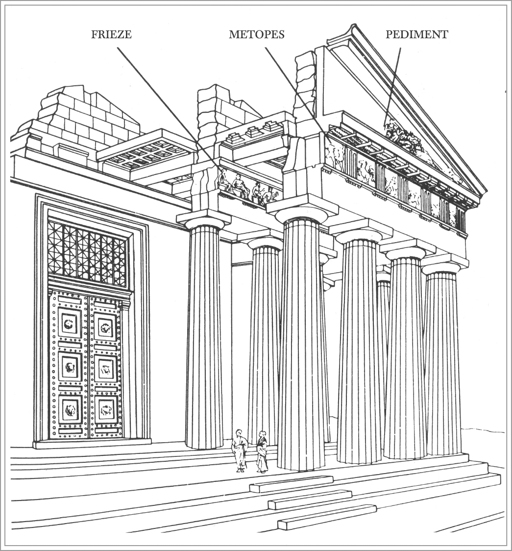

He also describes in detail the monumental gold and ivory statue, the so-called Athena Parthenos, housed within the east room of the temple. Dazzled by the radiance of the colossal image, Pausanias heads straight for the east door to peer inside at the statue, apparently never looking up to notice the frieze set high among the shadows within the porch (below).

Had he looked up, Pausanias might have caught a glimpse of the lively spectacle, a band of sculptured relief showing 378 human and 245 animal figures and running some 160 meters (525 feet) around the top of the cella wall within the colonnade. Set at a height of 14 meters, or about 46 feet, and deeply shaded under the ceiling of the peristyle for most of the day, the frieze measures just over 1 meter from top to bottom, or roughly 3 feet 4 inches in height.

Parthenon’s sculptural program: pediments, metopes, and frieze. (illustration credit

ill.46

)

Much has been written in recent years about the viewing of the Parthenon frieze, the framing of its images between the columns, and the optimal lines of sight for the spectators down below.

16

Truth be told, the frieze would have been difficult to see from ground level. The earthbound Athenian would, of course, have made out the profiles of figures set against the frieze’s deep blue painted background. Skin pigments of reddish brown for men and white for women would have made the sexes distinguishable at a distance. Light green and red pigment preserved on costumes worn by some of the horsemen, and traces of green paint on a few of the rocks shown on the west frieze, give a hint of how vibrantly colored the frieze originally appeared. Gilding is preserved on the heads of certain figures, enlivening their hair. Horses were painted in white, black, and brown. There are drill holes for the attachment of bronze bridles and reins, gilded sandal straps, and other details that would have fairly glistened.

17

Smaller details in the carving would have been obscure, like the composit

ion as a whole.

18

But viewers would have already known the subject matter, thus easily recognizing the figures glimpsed between the columns. Still, to peer straight up at the frieze from thirty to forty feet below would have required an inordinate amount of squinting and neck craning.

19

In fact, the primary

intended viewers of the Parthenon frieze were not mortal visitors to the Acropolis but the gods eternally gazing down upon it. As

Brunilde Ridgway’s aptly titled book expresses it, sculptured images on Greek temples were meant as “prayers in stone.”

20

Conditioned as we are to focus on our own experience as viewers, it is hard to fathom a world in which the pleasure of the gods came first. But it did. The perfection of the Parthenon frieze is all the more astonishing when we consider that, apart from the sculptors who carved it in situ, very few people had the opportunity to see this masterwork up close.

21

While the principal purpose of architectural sculpture was to delight the gods, humans were certainly enthralled and edified by the sculptured decoration of Greek temples.

Euripides’s sketch of a chorus of Athenian serving maids admiring the sculptures of the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi provides a rare glimpse into the viewing experience of pilgrims at a Panhellenic shrine. The young Ion, servant of Apollo’s temple, guides the Athenian women through the

iconography, pointing out the hero

Herakles (assisted by

Iolaos) battling the

Lernaean Hydra in one sculptured panel. “Friend, look over here!…I see him,” cry the chorus of

serving maids, adding, “I cast my eye everywhere.” Ion draws the women’s attention to an image of the goddess Athena shaking her

Gorgon shield at

Enkelados in the battle of the gods and the Giants. “I see my goddess, Pallas!” chimes the chorus, in an ecstatic moment of recognition when the

cosmic war of aeons past is suddenly rendered present.

22

Visual culture was intended not merely as an aesthetic experience but also to inform and educate, particularly in matters of the common faith. Above all, images rendered the gods and heroes present within the sanctuary. The power of the image was much nearer the power of reality in such a time and place where there were no mere likenesses.

The word for “sculpture” or “statue” in Greek was

agalma

, which literally means “pleasing gift” or “delight.”

23

Works of art needed to be perfect in order to please and honor divinities in a fitting way. It is often noted, sometimes with surprise, that the backsides of the Parthenon’s pedimental figures are carved, even though they would never have been seen once put in place (

this page

, second figure). Set close against the tympanum wall of the gable, the posteriors of these figures would be known only to the gods, who might well be offended by imperfections humans would not notice.

Contrary to this understanding, it is the human response to the Parthenon sculptures that has preoccupied commentators over the centuries. The first post-antique description of the temple we have is that of Niccolò da Martoni, who wrote about it in his

Pilgrimage Book

after a visit to Athens in February 1395.

24

By this time the Parthenon had been transformed, first into a Christian church, becoming Orthodox with the great schism of

Christianity around 1000 and then, after the Frankish conquest of 1204, into a Latin cathedral known as

Notre-Dame d’Athènes.

25

Martoni praises the precious icons that he sees within the church as well as the relics of saints and a copy of the gospels said to have been transcribed by the emperor Constantine’s mother, Helen. Martoni then describes the Parthenon itself: its size, the number of its columns (he counts sixty), its construction, and its sculptural decoration. He is particularly impressed by a story he was told regarding the temple’s marble doors: these were the gates of

Troy, brought to Athens by victorious Greeks after the

Trojan War. Martoni’s account demonstrates the staying power of local narrative and its role in shaping, and reshaping, the myth-history of the Parthenon.

Without an ancient source to confirm what ancient viewers saw in the

Parthenon frieze, post-antique interpreters have been free to reconstruct meanings on their own. The first to comment directly on the frieze was Cyriaco de’ Pizzicolli, known as Cyriacos of Ancona. This Italian merchant, humanist, and antiquarian served as envoy for

Pope Eugenius IV. He visited Athens in 1436 and in 1444, writing detailed letters, keeping diaries, and making careful drawings on each trip.

26

A fire at the library of Pesaro in 1514 destroyed Cyriacos’s original drawings of the Parthenon. But copies had been made, some more reliable than others, to give us a good sense of what he saw and how he saw it. One reproduction, made in silverpoint as a presentation sample of his work for

Pietro Donato, bishop of Padua, reproduces a drawing (following page) from a letter Cyriacos wrote to

Andreolo Giustiniani-Banca from the island of Chios on March 29, 1444.

27

In a Latin text above the drawing, Cyriacos writes, “My special preference was to revisit…[the] greatly celebrated temple of the divine Pallas and to examine it more carefully from every angle. Built of solid, finished marble, it was the admirable work of Phidias, as we know from the testimony of Aristotle’s instructions to king Alexander as well as from our own Pliny.” Cyriacos goes on to give a detailed description of the Parthenon: “It is raised up on 58 columns: 12 at each of its two fronts, two rows of six in the middle and, outside the walls, seventeen along each side.”

28