The Parthenon Enigma (25 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

The fifty-five lines from Euripides’s

Erechtheus

that Lykourgos then speaks represent the longest quotation of any Greek play by an ancient orator. Queen Praxithea’s horrific proposition manifests the most basic principles of Athenian patriotism: a conviction that Athens is better than all other cities; pride in the autochthonous origins of its people; devotion to the forefathers and their ancestral

religion; the primacy over individual self-interest of the

common good, toward which the citizen properly feels an overwhelming sense of love, duty, and honor; boldness and resilience; the ability to take quick action; and above all a readiness to die for one’s country. Praxithea answers her husband without hesitation:

(1) Favors, when granted in a noble way, please people even more. When one acts, but acts slowly, this is less noble. I, then, will give

my daughter to be killed. I take many things into account. First, I could not find a better city than this one [Athens]. We are a people born from this land, not brought in from elsewhere. Other cities are founded as if by throws of the dice; (10) people are imported to them, different ones from different places. A person who moves from one city to another is like a peg badly fitted into a piece of wood: a citizen in name, but not in action.

Secondly, our very reason for bearing

children is to protect the

altars of the gods and our fatherland. The city as a whole has one name but many dwell in it. Is it right for me to destroy all these when it is possible for me to give one child to die on behalf of all? I can count and distinguish between things larger and smaller. (20) The ruin of one person’s house is of less consequence and brings less grief than that of the whole city.

If our household had a harvest of sons in it, rather than daughters, and the flame of war were engulfing the city, would I not send my sons into battle with spears, fearing for their deaths? No, let me have daughters who can fight and stand out among men and not be mere figures raised in the city for no purpose. When mothers’ tears send their children off to battle, many men become soft. (30) I hate women who choose life for their children rather than the

common good, or urge cowardice. Sons, if they die in battle, share a common tomb with many others and equal glory. But my daughter will be awarded one crown all to herself when she dies on behalf of this city, and in doing so she will also save her mother, and you [Erechtheus], and her two sisters … are these things not rewards in themselves?

And so, I shall give this girl, who is not mine except through birth, to be sacrificed in defense of our land. (40) If this city is destroyed, what share in my children’s lives will I then have? Is it not better that the whole be saved by one of us doing our part?…And as for the matter which most concerns the people at large, there is no-one, while I live and breathe, who will cast out the ancient holy laws of our forefathers. Nor will Eumolpos and his Thracian army ever—in place of the olive tree and golden

Gorgon head—plant the trident on this city’s foundations and crown it with garlands, thus dishonoring the worship of Pallas [Athena].

(50) Citizens, make use of the offspring of my labor pains, save yourselves, be victorious! Not for one life will I refuse to save our city.

O fatherland, I wish that all who dwell in you would love you as much as I do! Then we would live in you untroubled and you would never suffer any harm.

Lykourgos,

Against Leokrates

100 = Euripides,

Erechtheus

F 360 Kannicht

122

What Praxithea does not know is that her daughters have already sworn an oath of their own: if any one of them should die, so shall the others.

123

The oath of Erechtheus’s daughters is thus invoked by Lykourgos alongside the oath of the ephebes and that of the Greeks at Plataia. It is all to remind the jurors that at the very core of the citizen’s sacred relationship to the state was the solemn act of

oath taking, the very tie that binds. In this, Lykourgos echoes the words of his teacher,

Isokrates: “First, venerate what relates to the gods, not only by performing sacrifices but also by fulfilling your oaths. Sacrifices are a sign of material affluence, but abiding by oaths is evidence of a noble character.”

124

Finishing his long quotation from the

Erechtheus

, Lykourgos closes his case: “On these verses, gentlemen, your fathers were brought up,” emphasizing the centrality of Euripides’s text in the traditional education of Athenian youth.

125

He then asks the jurors to consider how Queen Praxithea, against a mother’s instinct, loved her country more than her own

children and was willing to give them in ultimate sacrifice to save the city. Importantly, Praxithea acts quickly and, thus, nobly in ensuring salvation for Athens.

126

If women can bring themselves to act like this, Lykourgos declaims, then men (like Leokrates) “should show toward their country a devotion which cannot be surpassed.”

127

If all citizens loved Athens as Praxithea did, it would flourish and remain ever safe from harm. Leokrates doesn’t love Athens, and so he must be punished.

Lykourgos asserts that Athenians owe a debt to Euripides for passing this story down to them, thus providing a

paradeigma

(“fine example”) that citizens can keep before them to “implant in their hearts a love of their city.”

128

By no coincidence, this same word appears in the Periklean funeral oration: Athens does not copy (

mimeitai

) other cities but is a

paradeigma

to them. Lykourgos is doubtless recalling that great moment of oratory.

129

But all these Lykourgan flourishes would not achieve their intent: in the end, despite abundant evidence and exhortation, the jury would acquit Leokrates by a single vote. The verdict

must have surely confirmed Lykourgos’s worst fears about the hearts of his fellow citizens. For all he had done in his political life to uphold and reanimate the values that had made Athens great, here was painful evidence that at least for half of the citizenry the days when those values were truly inviolable were past. The good of Athens above all was sacred no more to the Athenians, the prospect of Macedonian domination after Chaironeia perhaps having finished a job that the

radical democracy, with all its bountiful blandishments, had begun.

NEVERTHELESS, LYKOURGOS

’

S SPEECH

Against Leokrates

was not entirely in vain. Without it, we would know very little of Euripides’s lost play or of the story of

Erechtheus and the sacrifice of his daughters, a centrally important one for our purposes. As the great progenitor in whom the primordial past culminates and through whom the Athenians enter history, Erechtheus represents a kind of missing link, his place in the Parthenon’s sweep of the ages unsuspected until recently. In fact, the family of Erechtheus can now be understood to stand at the very heart of the Parthenon sculptural program. This recognition will furnish the key to understanding the temple’s most enigmatic and prominent imagery, and in so doing lead us to revise our most basic understanding of the building itself. It is the story of the magnanimity of the royal house of Erechtheus that brings so vividly to life that most essential conviction expressed by Perikles in his funeral oration: Athens is worth dying for. And it turns out that even as the once indelible principle was fading, someone saw fit to illustrate it for all time in the holiest of places.

4

THE ULTIMATE SACRIFICE

Founding Father, Mother, Daughters

THE YEAR WAS

1901. The site was

Medinet Ghoran.

Pierre Jouguet and his team of excavators set off across the Egyptian sands to the southwest of the

Fayum oasis. Here, they would dig through the winter months, from January through March, efforts that were mightily repaid. The French team unearthed hundreds of mummies from a broad network of rock-cut tombs comprising a vast Hellenistic cemetery.

1

While the burials themselves were not particularly rich, the

mummy casings would prove, some sixty years later, to be a treasure trove.

Those casings were not of gold or gilded wood, like Tutankhamen’s coffin and those of other well-known Egyptian royalty. Rather, they were of papier-mâché. For more cost-conscious customers, morticians of

Hellenistic Egypt used discarded scraps of

papyrus, pasting them together over the linen wrappings of the dead. When it had dried and hardened, the resulting cartonnage could be plastered, painted, or even gilded to give the impression of a much finer material. This treatment is typical of burials of commoners during the last three centuries

B.C.

, when

Alexander the Great’s Macedonian general Ptolemy I and his descendants ruled Egypt.

The ink on those paper scraps did not dissolve, and so together with the earthly remains, the texts that had originally been copied onto those papyri by scribes at Alexandria and elsewhere survived. More copies than ever intended: if a scribe made an error in his transcription, the whole sheet was discarded, only perfect copies being good enough for the libraries of the Hellenistic world. But as paper was precious, the abortive imperfect copies would be sent off to morticians for making coffins. And so Hellenistic Egyptian tombs and their mummy casings have become crucial sources for the recovery of lost and unknown texts.

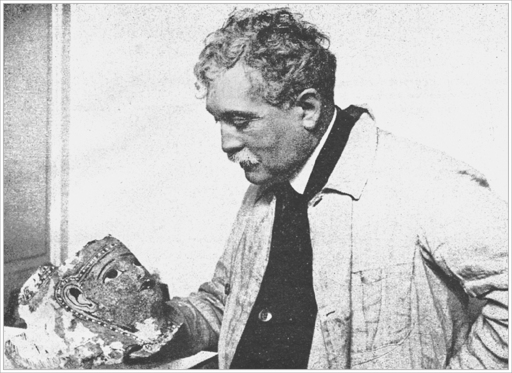

Pierre Jouguet contemplating a mummy casing.

La Revue du Caire

13, no. 130 (1950). (illustration credit

ill.39

)

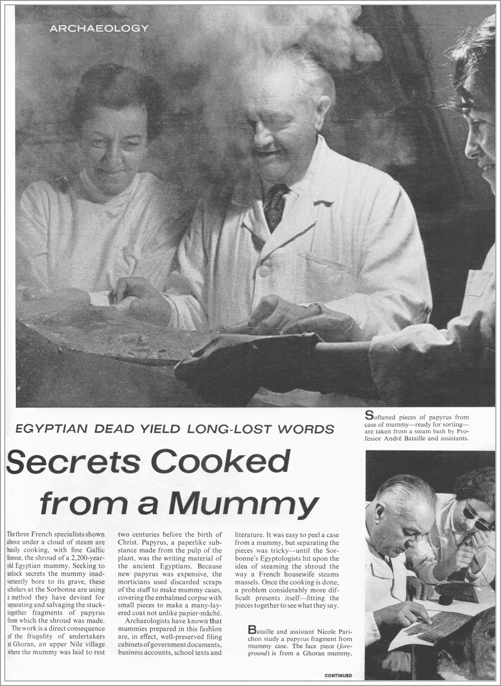

Jouguet brought dozens of mummies back from the trenches of Medinet Ghoran for study at the Institutes of Papyrology in Paris and Lille (above). From these, he managed to extract a number of Greek and demotic Egyptian texts, though it proved difficult to separate the fragile papyrus layers without damaging them to the point of losing what had been written. This would remain the case until the early 1960s, when Professor

André Bataille and Mlle

Nicole Parichon of the

Sorbonne’s

Institut de Papyrologie developed a new technique, first soaking the cartonnages in a 13 percent solution of hydrochloric acid, heated to 70 degrees Fahrenheit, and then placing them in a steam bath of 10 percent glycerin solution. This dissolved the glue and allowed individual sheets to be peeled apart, revealing lines of Greek not seen since the

third century

B.C.

The innovation caused something of a popular sensation,

Life

magazine (below) proclaiming in November 1963, “Secrets Cooked from a Mummy.”

2

In 1965, however, what might be viewed as the “curse of the mummy” struck.

3

Crossing a street in central Paris, Bataille was hit by a car and killed. But the papyrus fragments he had extracted back on September 19, 1962, had already created a buzz. Mummy casings 24 and 25 had yielded texts from a Greek comedy, the

Sikyonios

(“the man from Sikyon,” a city in the Peloponnese not far from Corinth), together with the name of its author, Menander. Written in the late fourth or early third century

B.C.

, the play was already known from 150 lines extracted from the mummies by Jouguet just a few years after their discovery.

Remarkably, the new additions belonged to the very same manuscript Jouguet had identified sixty years before, suggesting that a single papyrus scroll had been recycled across three different mummies!