The Parthenon Enigma (20 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

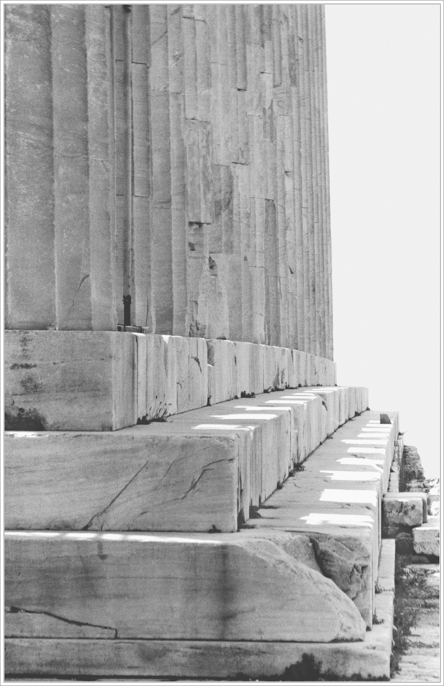

Perhaps in nothing did the Parthenon’s architects and engineers outdo themselves so much as in the advanced use of optical refinements, which they raised to a high art. Builders had for some years been exploring remedies for apparent distortions experienced when viewing large temples from a distance. An allusion of sagging is seen at the centers of the long horizontal lines of the

stylobate, as well as the lower two steps beneath it (stereobate), and in the cornice (architrave or entablature) up above. An extraordinary correction was found to remedy this illusion by making all horizontal surfaces bow upward at center.

54

Thus, on all four sides of the Parthenon we see upwardly curving surfaces and lines. For example, the steps on the flanks of the platform arch up 6.75 centimeters

(2.66 inches) higher at their centers than at their ends (previous page). So, too, do the horizontal lines of the architrave bow up in the middle. A breathtaking level of technical sophistication went into the execution of these adjustments to exacting tolerances. Ingenious combinations of reverse asymmetry can be detected, along with slight diminutions in curvature, all painstakingly worked out to achieve subtle, and enormously pleasing, visual effects.

Curvature of

krepidoma

, north steps of Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.30

)

It has long been noted that there are few, if any, straight lines in the Parthenon. First, the very platform on which it sits tilts up, from a low of 3 centimeters (1.2 inches) at the east end to a high of 5 centimeters (1.9 inches) at the west.

55

This makes for an imposing visual impression as one enters the Acropolis through the Propylaia: the giant west façade of the Parthenon tilts high and looms large (

this page

). In addition, the side walls of the Parthenon lean slightly inward, as do each of the forty-six columns of the peristyle. Indeed, if the axes of the flanking columns were extended into the sky, they would meet 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles) above the platform on which they stand.

56

When we look at the entablature and its

Doric frieze, we see that the metopes tilt slightly outward while the

triglyphs slant in. And so, from top to bottom, the Parthenon tips, slants, recedes, inclines, and bows, all the while transmitting an overwhelming sense of harmony and balance.

The Parthenon’s colonnade epitomizes the post-and-lintel system of load bearing in classical architecture. Yet here, too, subtle adjustments trick the eye to compelling effect, to create a reassuring sense of order and solidity while still appearing fascinatingly delicate. The columns taper upward, so they are wider at the base than at the top. At the same time, they swell outward at their midpoint, a phenomenon known as

entasis, which gives the appearance of a flexed muscle, as if bulging as it bears the weight. The columns at the very corners of the temple are slightly thicker than the others, creating the impression of extra solidity here on the flanks. Similarly, the final two columns on either end of the façades are not as far apart as other adjacent columns. This device, known as

corner contraction, allows the second-from-the-end columns to sit directly below triglyphs. Thus, the corner triglyphs are not centered above the corner columns but rest at the corners of the entablature. The logic of this was considered far more satisfying than centered corner triglyphs with impossible partial metopes at the corners.

All these calculated differences and variations are governed by a

complex system based on a ratio of 4:9, pulling the building (in both plan and elevation) into a unified whole.

57

The precision with which the ratio is observed among the individual proportions of the Parthenon is nothing short of astonishing: it governs the height of the columns and entablature to the width of the stylobate; the minimal column diameter to the axial distance between them; the width of the stylobate to its length. The result is a kind of buoyancy, a sublime integration of disparate members that is organic, almost alive as the Parthenon seems to breathe and flex supporting its Pentelic load. The American Beaux Arts architect

Ernest Flagg likened the effect of these ratios to that of aural harmony: “The hearer may be entirely ignorant of the methods used, yet charmed by the results. So, too, the observer of harmonious dimensions may be ignorant of their very existence, yet captivated by them.”

58

This visual perfection could not have been achieved without a highly evolved and supremely disciplined technical competency. The fluting of the columns, the carving of the sculptures, the smoothing of surfaces to be joined, indeed every block on the Parthenon was finished on-site. Stone sanding plates enabled artisans to finish surfaces to an accuracy of one-twentieth of a millimeter, so that individual blocks might rest seamlessly against each other. But the passage of time itself has accentuated the uncanny impression of perfect wholeness. One of the most fascinating discoveries made by Korres is that after centuries of constant pressure exerted by the blocks upon one another, granules of

marble have fused from one slab into the next, creating a solid mass of stone. Korres calls this

erpismos

, or “snaking,” within the crystalline structure of the marble, the arrangement of individual granules deformed into an undulating path.

59

He was able to observe this phenomenon following an earthquake in 1981 when blocks in the Parthenon’s

krepidoma

separated enough that he could peer into the core of the platform. What Korres saw was astonishing: discrete blocks seamlessly fused together. This makes the metaphor of the Parthenon as a reconstituted Mount Pentelikon all the more powerful.

OF ALL THE INNOVATIONS

introduced by the Parthenon, however, it is the extraordinary abundance of sculptural decoration that is most overwhelming. Nothing like it had been attempted before: two giant and lavishly adorned pediments, each bursting with dozens of

larger-than-life-size figures; a

Doric frieze with an unprecedented ninety-two sculptured

metopes wrapping around the entire exterior of the temple; and an astounding 160 meters (525 feet) of continuous sculptured frieze, set high on the cella wall within the peristyle. Visual pomposity was entirely of a piece with the aim of proving Athens supreme. But even more important, and just as we have seen on the great temples of the Archaic Acropolis, the Parthenon’s sculptural program is steeped in

genealogical narratives that beckon ever backward across imagined aeons. In an age without scriptures or media, this great billboard of the polis held up a constant reminder of just who the Athenians were and where they came from. It is precisely this projection of vast strata of time through monumental sculptures that made Athenian visual art so compelling to the Athenian mind. We cannot remotely understand the temple’s ultimate significance, beyond its status as an exercise in formal perfection, without understanding the stories that these sculptures tell.

The Parthenon’s east pediment gives us the very beginnings of Athenian genealogical history: the

birth of Athena set in

Hesiod’s Golden Age. Its companion pediment at the west presents the birth of Athens itself, that is, the primeval contest between Athena and

Poseidon for divine patronage of the city. This event is set during the reign of King Kekrops in the first

Bronze Age. Just beneath Athena’s birth scene we find in the east metopes the cosmic battle of the gods and the Giants. Of course, as the primary façade, or “front,” of the Parthenon, this east end appropriately shows a profusion of divinities, both in the pediment and on the metopes. On the south and west flanks we find metopes that tell stories drawn from a slightly later era, the second Bronze Age, when the greatest of Athenian heroes,

Theseus, battled the Amazons (west metopes) and the monstrous Centaurs (south metopes). Finally, the most consequential “boundary event” of the late Bronze Age—the Trojan War—is narrated across the north metopes. This saga was for the Greeks the ultimate marker between mythical and truly historic times.

When

Pausanias visited the Parthenon six hundred years after it was built, he admired the sculptures filling the pediments as well as Pheidias’s magisterial image of Athena housed within but made no mention of the metopes, the first of the figured decoration to be completed on the temple. Never before had this element—roughly square panels, which on the Doric friezes alternate with blocks marked with three vertical bars, called

triglyphs—been carved with figured reliefs all around

an entire temple. To do this on the Parthenon (the largest of all

Doric temples) meant fourteen figured panels on the east and west and thirty-two on the north and south. Perhaps surprisingly on a building of such exacting standards, these sculptures show an extraordinary range in style and execution, likely reflecting numbers of artists and apprentices on the job. Older sculptors, trained in the so-called Severe style of the 470s–450s

B.C.

, might have looked back to the example of sculptured decoration on Zeus’s temple at Olympia. But younger sculptors, inclined to look forward, experimented with innovative forms and compositions to create what has been called the

high classical style. And so, among the Parthenon metopes, the sublimity of certain figures contrasts markedly with the awkwardness of others. This is especially true of the south metopes, depicting the battle of the

Lapiths and the Centaurs; the variation in approach and competency is conspicuous (

this page

–

this page

).

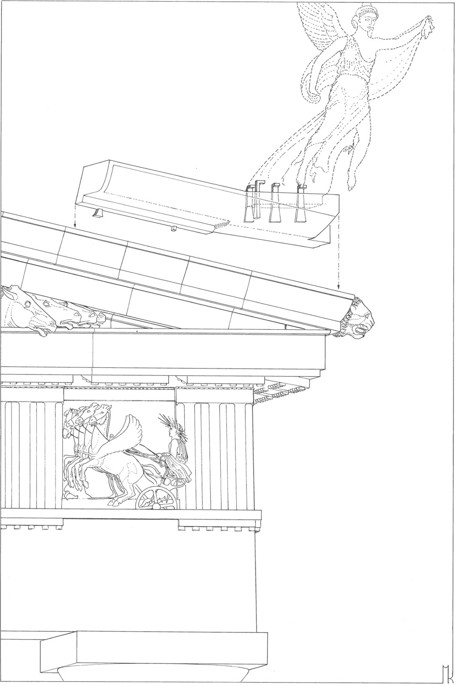

Manolis Korres’s reconstruction of the northeast corner of the Parthenon brings to life the seamless integration of sculptures within the architectural frame (following page). A winged Nike alights on the rooftop, signaling the Parthenon’s role as victory monument, an identity to which we shall return. One can only imagine the effect of Nikai akroteria “hovering” above each of the four corners, bringing airborne dynamism to the pulsing earthbound frame. (Meanwhile, the peaks of the gables were surmounted by floral akroteria showing akanthos leaves. See insert

this page

, bottom.) Just below the Nike figure, rainwater would have gushed from the lion’s-head spouts that drained the gutters, lending further movement and energy.

60

Spilling out from the narrowed corner of the pediment’s frame, four vigorously modeled horse heads, nostrils flaring and mouths agape, are shown pulling against the bit. The horses draw the chariot of the setting

Moon (Selene) as she sinks into the sea. And just beneath, we see a metope showing the Sun (

Helios) driving his quadriga in the opposite direction, up from the watery depths. At lower right, two small fish jump among the waves, and at left a small duck skims the water. Bright painted colors and bronze attachments would have further animated the figures populating this densely imagined universe. Metal wings would have spread from Helios’s team, while a bronze harness yoked them to the chariot. Helios himself would have been crowned with a bronze sunburst, while a solar disk might have hung in the space above.

61

The god’s arrival signals the dawn of the day on which the cosmic battle of the Gigantomachy was fought. Gods and Giants can be seen raging on the thirteen other picture panels across this façade, but the condition of these east metopes is so poor that only the barest outline of figures can be made out. Nonetheless, we can distinguish Hermes, Dionysos, Ares, Athena, Eros, Zeus, Poseidon, and other Olympians taking on the deadly Giants in a contest already celebrated on the Old Athena Temple at the end of the sixth century (

this page

).

Reconstruction drawing of northeast cornice of Parthenon with Nike akroterion, horses from Selene’s chariot in pediment, and Helios metope, by M. Korres. (illustration credit

ill.31

)