The Parthenon Enigma (16 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

For in the East, King Darius of Persia was busy with plans of his own, ever expanding his empire westward into territories long held by the Greeks of

Asia Minor (on the western coast of present-day Turkey). By 499

B.C.

, these Ionian states had had enough and pushed back against

Persian aggression. The Athenians sent help in the form of ships and troops but paid heavily for this support. The Persians crushed the Ionian revolt and then turned their sights, and revenge, squarely upon the Athenians themselves. War was inevitable. With the Persian threat looming, the populist leader

Themistokles, elected archon in 493, diverted the Athenian treasury to a more urgent need than that of building a new temple. He focused Attic resources on the creation of a fleet of warships, galvanizing the city’s maritime assets in a move that would prove indispensable to Athenian survival.

In August of 490

B.C.

, tens of thousands of Persian troops landed on Marathon beach, the turncoat Hippias showing the way.

Plutarch tells us that the hero

Theseus appeared to the Athenians in the course of the ensuing battle, rushing out in front of them in full armor and leading them to victory just as in days of old.

98

In what is regarded as one of the greatest military watersheds of all time, 6,400 Persians are said to have fallen that day to Athenian losses of just 192.

99

The extraordinary bravery of the Athenian soldiers and their Plataian allies instantly catapulted them to epic heroic status. The Marathon dead were awarded the extraordinary honor of burial on the spot where they fell, placed together in one great tumulus that became a monument unto itself.

100

In the wake of the triumph at Marathon, construction began in earnest on the immediate predecessor of the Parthenon, the so-called Older Parthenon.

101

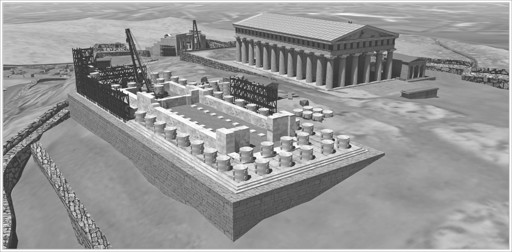

Athena needed to be thanked and honored for the astonishing victory. The new temple would have six columns on its ends and sixteen running down its sides (

this page

and following page), and for the first time ever the Athenians would build a temple entirely of

marble. This marble would come from their own Mount

Pentelikon, the city’s swelling pride permitting no import of materials.

102

But Persian fury would intervene. A vast Persian army and navy advanced into Attica in 480

B.C.

to avenge their defeat at Marathon. Now under the command of Darius’s son Xerxes, the enemy first won a critical battle at Thermopylai, defeating the 300 valiant Spartans under the command of Leonidas, before marching on to Athens. Seeing what was coming and discouraged by reports that the sacred snake had disappeared from the Acropolis, most Athenians evacuated the city, seeking refuge on the nearby island of Salamis. Everyone knew that the Persian attack would be violent, but no one was prepared for the devastating destruction of the most holy buildings on the Acropolis itself. The Persian army surrounded the Sacred Rock, one division positioning itself on the Areopagus to better shoot flaming arrows up at the wooden ramparts. A few Persian soldiers scaled the precipitous and unguarded eastern cliff of the Acropolis, just above the sanctuary of Aglauros (insert

this page

, bottom). Once on top, they opened the western gate, and the full Persian army flooded in, massacring those few suppliants and defenders who had chosen to stay, plundering the temples, and setting the whole citadel ablaze. It was an atrocity beyond comprehension for the Greeks. Hellenes had long followed a code by which the holy places of enemies were respected and spared during war. After all, their destruction was certain to incur divine wrath. But the Persians worshipped other gods and showed no respect for the Olympians.

Hypothetical visualization of Older Parthenon and Old Athena Temple in 480 B.C., prior to Persian siege. (illustration credit

ill.23

)

The Old Athena Temple was hit hard in the siege, as was the Older Parthenon still under construction to the south of it.

Manolis Korres, the architect-engineer-archaeologist who oversaw the

Acropolis Restoration Program for some thirty years, has established that the Older

Parthenon was standing to a height of just two or three column drums, still unfluted, when the

Persians attacked. But there was wooden scaffolding set up all around it, providing plenty of fuel to feed the flames (facing page).

103

Korres has identified thermal fractures on many of the temple’s blocks, including the upper steps of its platform, which would be reshaped, capped, and reused more than thirty years later for the Periklean Parthenon.

104

The Athenians did not despair but, keeping hope, retrenched and brilliantly expelled the Persians just a year later. Thanks to

Themistokles’s insight and careful preparation, they had developed their secret weapon: a powerful fleet of two hundred warships manned by a legion of highly trained and financially compensated oarsmen drawn from the

thetes

, the poorest of Athenian citizen classes. Themistokles himself would lead the stunning naval victory off the island of Salamis in September of 480, a victory that would soon be followed in 479 by sound defeat of the Persian land forces, deprived of their naval support, at the

Battle of Plataia.

105

Thucydides tells us that immediately after the “barbarians had departed from the land,” the Athenians brought their women,

children, and possessions back from their places of refuge and began “rebuilding their city and its walls.”

106

Any surviving blocks in

a condition to be reused were gathered up for hasty construction of the great defensive walls that Themistokles ordered for the immediate securing of the city. These included blocks fallen from the Acropolis buildings. Broken and battered Archaic statues, including the famous

korai

(“maidens”) that had once stood as sumptuous dedications to the goddess, were collected and buried in pits within the sanctuary, lovingly laid to rest within the sacred space.

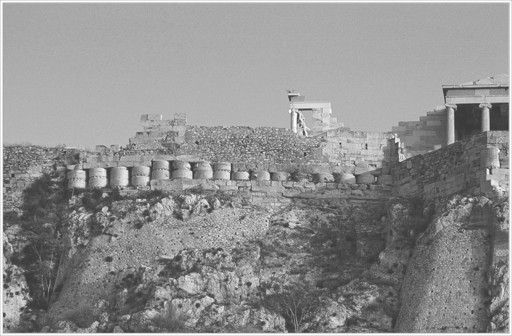

Display of reused column drums, north fortification wall, Athenian Acropolis. (illustration credit

ill.24

)

Column drums from the Older Parthenon and surviving triglyphs, metopes, architrave, and cornice blocks from the Old Athena Temple were salvaged and built into the Acropolis’s north fortification wall, no doubt under the watch of Themistokles (previous page).

107

That they are displayed in the same architectural order as they would have appeared on the temple (column drums carefully stacked to reconstruct “columns,” metopes and triglyphs reconstructed in their proper sequence) shows a reverential reconstruction meant to evoke the destroyed temples and not simply an expeditious reuse of architectural elements to strengthen the fortification wall. Thus these architectural relics formed a commemorative display: proof of the Persian atrocities and the destruction of the city’s most sacred shrines. They bore witness to the horrors suffered by a generation of Athenian heroes in the early decades of democracy. And so, the Athenians reconciled their desire to remember and their desire to create; their need to memorialize and their need to move forward.

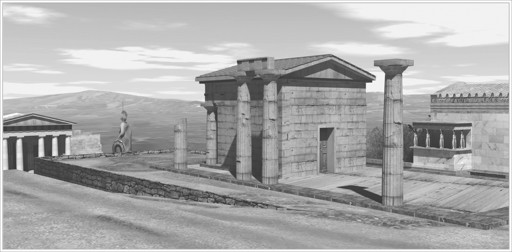

The Old Athena Temple was not completely destroyed in the Persian attack; its façades and part of its westernmost room (known as the

opisthodomos) seem to have remained standing while its roof and interior collapsed (facing page).

108

This would help explain why the

Erechtheion (built just to the north of it in the last quarter of the fifth century) respected its foundations and adopted such a peculiar design for its southern flank. Indeed, the long stretch of wall to the east of the Porch of the Maidens was left completely blank, something very strange within the larger scheme of Greek architecture. But if battered remains of the Old Athena Temple still occupied parts of the

Dörpfeld foundations at the time when the Erechtheion was built, this southern wall might have been left necessarily unadorned as it was mostly hidden by the standing ruins (facing page and

this page

). The Erechtheion’s karyatid porch extends farther south to encroach upon the Dörpfeld foundations at a place where the Old Athena Temple may have completely collapsed. While it is difficult to prove this was so, it does make sense and would continue the tradition in which ruined walls of earlier periods (see the Mycenaean fortifications,

this page

) were preserved and respected on the Acropolis as relics of the past. What is clear is that the Acropolis was ever a place of memory, bearing palpable witness to earlier eras, past struggles against deadly enemies, and the victories that defeated them. Again, in the absence of photography or film, it was essential to preserve tangible evidence of past history, or else future generations might forget it, or not believe it at all.

Hypothetical visualization of surviving opisthodomos of the Old Athena Temple with Erechtheion at right.

Like the cosmic

battles of

Zeus and Typhon projected on the

Bluebeard Temple pediment and the clash of gods and Giants on the Old Athena Temple, a new generation of terrifying enemies confronted Athenians of the early fifth century. The Persian behemoth had raised its ugly head, but this monster, like

Drako, Typhon, Triton, the Hydra, and

Enkelados before it, would be soundly slain, this time, in the waters off Salamis and in the wheat fields of Plataia. (illustration credit

ill.25

)

3

PERIKLEAN POMP

The Parthenon Moment and Its Passing

PERIKLES WAS ABOUT FIFTEEN

when the smoke rose from the smoldering Acropolis in 480

B.C.

We cannot know if he watched with his family from Salamis, to which most Athenians fled. It is said that when the Athenian fleet routed the Persians, months later, in waters off that island, his (future) friend

Sophokles, aged sixteen, was chosen to lead the victory dance. Already renowned for his good looks and flair as an entertainer, Sophokles performed the triumphant paean, serving as top boy in the male chorus, an auspicious debut for one who would eventually rank among the greatest tragedians of all time.