The Parthenon Enigma (19 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

A decision had been made at the outset to build the Parthenon entirely of high-quality, fine-grained white marble from the city’s own Mount

Pentelikon. Thus, from top to bottom, from roof tiles to all three steps (

krepidoma

) of the platform on which the temple sits, to every last carved decoration, this thoroughly Athenian monument is made entirely of Athenian material. A hundred thousand tons of

Pentelic marble were carried up the Acropolis, re-creating a veritable “mountain of marble.” The Parthenon would be as solid, enduring, and dazzling as Mount Pentelikon itself.

Ancient sources name Iktinos as the designer/architect of the temple, and

Kallikrates as a sort of general contractor.

34

Writing some four centuries after the completion of the Parthenon,

Vitruvius names

Karpion as a co-author, with Iktinos, of a technical manual on its engineering, suggesting a key role for him, though he is unattested elsewhere.

35

Mnesikles is named as the architect of the

Propylaia, begun in the same year as the Parthenon. But of all the names that come down to us from the cohort of geniuses who conceived and executed the Periklean building program, it is that of

Pheidias, friend of Perikles, that figures most centrally as the general overseer of the Parthenon project.

36

Pheidias seems to have started his career as a painter (like his brother

Paionios) but soon focused on sculpture, winning some of the most coveted commissions of his day. A recognized talent already during

Kimon’s years of leadership, Pheidias had been selected to create a bronze statue group at

Delphi commemorating the Athenian victory at Marathon. Funded by a tithe of the Persian spoils, this monument featured Kimon’s own father,

Miltiades, hero of the battle, flanked by statues of Athena and Apollo. These were joined by images of the legendary Athenian kings

Erechtheus, Kekrops,

Pandion,

Theseus, and Theseus’s son

Akamas, indeed by all the heroes who gave their names to the ten tribes as reorganized by Kleisthenes.

37

Thus, the young Pheidias had early practice in carving the likeness of Erechtheus, experience that would serve him well in planning the

Parthenon frieze. It was also under Kimon that Pheidias created a gold and ivory statue of Athena for her temple at

Pellene in Achaia, a work that prefigured his chryselephantine statue of the Athena Parthenos. Pheidias’s most conspicuous commission was, of course, the

Bronze Athena that stood some 40 meters (130 feet) tall on the Athenian Acropolis, an image created in the 470s and financed from the Persian spoils at Salamis. The statue (

this page

) looked straight out the Propylaia toward Salamis, while the crest of its helmet is said to have been visible all the way from Sounion.

38

But Pheidias’s most famous creation of all was the colossal gold and ivory statue of Zeus he made for the temple at Olympia, an image that would become one of the

Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

By the time Pheidias unveiled the Athena Parthenos statue in 438

B.C.

, he stood accused in a high-profile lawsuit of embezzling gold intended for the cult image. This was part of a wave of legal actions that erupted at this time, owing to the diffusion of power within the radical democracy.

Before long, Perikles’s beloved Milesian mistress,

Aspasia, was charged with impiety.

Athenaeus, quoting

Antisthenes (a pupil of Sokrates), tells us how Perikles wept bitterly while pleading her case before the court.

39

And soon, new legislation was passed making it a crime to “teach about the heavens,” directly targeting Perikles’s teacher

Anaxagoras. Perikles himself had been accused of bribery and embezzlement, and it was when these charges failed to bring him down that his enemies resorted to assailing his inner circle.

Plutarch tells us that Pheidias eventually cleared his name by asking that the gold from the goddess’s statue be removed and weighed, thus proving that none was missing. But the accusers persisted, charging him with impiety for sneaking his own likeness and that of Perikles into the composition of the Amazonomachy shown on Athena’s shield, the friends allegedly resembling two Greek warriors portrayed there.

40

Convicted and exiled from Athens, the greatest sculptor of the Periklean age and chief overseer of the Parthenon project would die in jail.

IN PLANNING

the new temple of Athena, Pheidias and his team of architects had looked back to the Older Parthenon, a building begun around 488 but destroyed by the Persians before it could be finished.

41

Its giant foundation, rising some 11 meters (36 feet)from the bedrock on the south side, would be used to support the new structure. Since its uppermost courses were damaged by fire, the great three-stepped platform would be entirely encased within newly hewn marble blocks. Some economies were observed, such as the use of blocks that had been cut for the Older Parthenon but were still lying in the quarries of Mount

Pentelikon or atop the Acropolis itself. It has been suggested that one-quarter of the total construction cost of the Parthenon was saved by the reuse of blocks prepared for the earlier structure.

42

The height of the steps of the Parthenon’s

krepidoma

, including the top step (stylobate), the steps leading into the cella, and the diameter of the peristyle columns, was kept identical to that of the Older Parthenon, making the salvage possible.

43

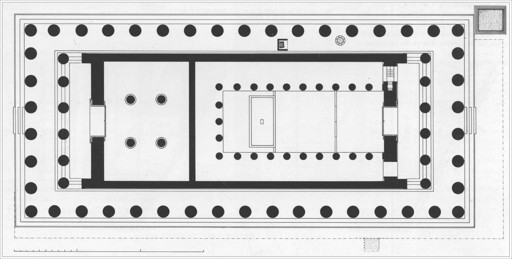

Still, there were many changes in plan. The

footprint of the new Parthenon was extended to the north (following page), making it much wider but somewhat shorter than its predecessor at 30.80 by 69.51 meters (101 by 228 feet). To accommodate the extra width, two columns were added to the façades, making for a peristyle of eight columns

rather than six at front and back and seventeen down the sides.

44

The new proportions allowed for a more capacious interior of the cella, no doubt in anticipation of Pheidias’s monumental statue of Athena.

45

The Parthenon’s peristyle thus comprises forty-six columns in all, with the spaces between the columns at front and back screened by metal grilles and gates to secure the treasure held within. A second row of six columns was added behind the peristyle on the façades, creating a prostyle arrangement reminiscent of the great sixth-century

Ionic temples of East Greece, the massive dipteral shrines at

Samos,

Ephesos, and

Didyma.

46

This innovation is contrary to

Doric conventions that call for a single colonnade wrapping around the cella. Indeed, the Parthenon integrates many Ionic features into an overall Doric program: not just the double row of columns at front and back, but also the bead and reel moldings on the Doric frieze crown, the continuous Ionic frieze set high within the colonnade, and four Ionic bases (possibly supporting

proto-Corinthian columns) that stood in the temple’s westernmost room (

this page

).

47

Widening the platform 5 meters (16 feet) to the north had another consequence: the footprint overlapped a preexisting shrine. Out of respect for the continuity of this holy place, the spot was marked by a small temple structure (

naiskos

) built exactly above it, within the Parthenon’s north colonnade (below and facing page).

Manolis Korres has identified evidence for this

naiskos

set between the seventh and the eighth columns (from the east end) of the colonnade as well as a circular

altar that sat to the east of the structure, between the fifth and the sixth columns (from the peristyle’s east end).

48

The altar indicates that

ritual observance was continued at this new incarnation of the earlier shrine. Fascinatingly, the

naiskos

is aligned on the same axis as the

Older Parthenon, rather than along the slightly shifted one of the new Parthenon. We will return to the puzzle of this

naiskos

in

chapter 6

, but for now let us recognize the care the builders took to preserve the continuity of this especially sacred spot.

Plan of Parthenon, with Older Parthenon (dashed line) beneath;

naiskos

and altar in north peristyle, by M. Korres. (illustration credit

ill.28

)

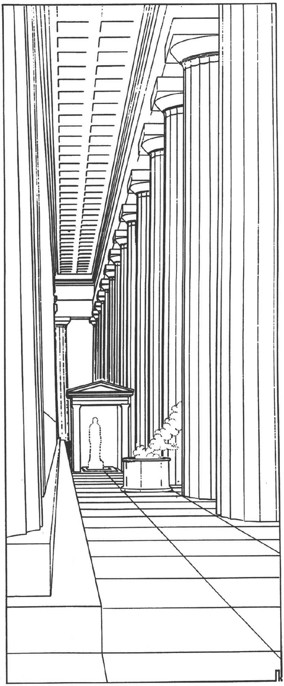

Reconstruction drawing of the Parthenon’s north peristyle with

naiskos

and altar, by M. Korres. (illustration credit

ill.29

)

Another point of reference for the new temple was the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia. Finished in 456

B.C.

, the temple was now the largest in Greece.

49

Naturally, the architects at Athens viewed the Olympian shrine with an eye to surpassing it. The Parthenon’s exterior columns are, in fact, exactly the same height as those of the Zeus temple: 10.43 meters (34.21 feet). But the Parthenon’s extra width (eight columns across the façade to Olympia’s six) and the use of

marble rather than soft limestone make the building incomparably more magnificent.

The new Parthenon maintained the same basic plan as its predecessor: a great room at the front on its eastern end and a completely separate, smaller room at the west, or back of the building (

this page

). Inscribed inventories dated 434/433

B.C.

refer to this easternmost room as the

hekatompedon

, or “hundred-footer,” just as we have seen for the temple that might have stood on this spot during the sixth century, that which held the

Bluebeard pediment.

50

Two windows pierced the eastern wall of the cella on either side of the doorway, allowing extra light to flood in upon Pheidias’s gold and ivory Athena. A recessed section of floor paving in front of the statue’s base might have accommodated a shallow pool of water. This would have facilitated humidification of the ivory components (susceptible to cracking if too dry) and would have reflected morning light from the east windows to better illuminate Athena’s image. The eastern cella featured an elegant means for supporting the roof: a two-tiered colonnade satisfied the canons of

Doric proportion (which didn’t allow for tall, slender columns) and, at the same time, created a transparent, screen-like arrangement that wrapped around the sides and back of Athena’s statue (insert

this page

, bottom). This increased the apparent size of the cult image and greatly enhanced the mystery of the space.

51

In contrast, the western room of the Parthenon was much smaller, measuring 13.37 by 19.17 meters (43.86 by 62.89 feet), with its greater dimension being north to south. Fifth-century inventories refer to this chamber as the

parthenon

, a word meaning “of the maidens,” the sense of which we shall discover in due course.

52

Its roof was supported by four slender columns. The outlines of their bases suggest not Doric but the canonical Attic

Ionic profile (toros-scotia-toros). This change of order was necessary since the ceiling of this chamber was higher than that of the peristyle; the use of stouter Doric columns would have made them impossibly large and there was no need for a two-tiered colonnade

arrangement here, as we saw in the eastern cella. And so, yet another innovative solution was devised:

Ionic columns (with more slender proportions) were introduced.

Poul Pedersen goes even a step further and suggests that these columns featured capitals that foreshadowed the Corinthian order, a point to which we will later return (

this page

).

53