The Parthenon Enigma (23 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

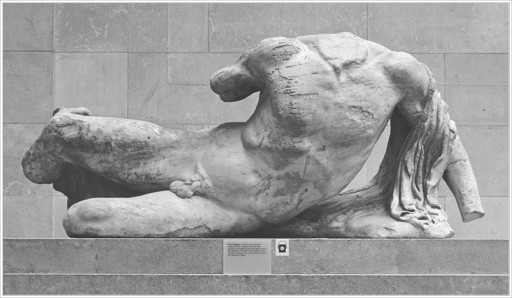

Kephisos River, west pediment, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.36

)

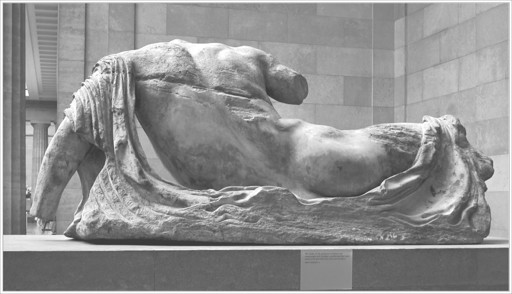

Kephisos River, west pediment, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.37

)

Athena’s victory was not the end of the contest exactly.

Poseidon’s

son

Eumolpos carries on his father’s bid for Athens, rallying an army of Thracians to take the city. In the ensuing battle, Erechtheus kills Eumolpos’s son

Himmarados before he himself is killed by Poseidon. Thus, the primeval clash is carried on through the generations that follow. This foundation myth may, in fact, speak to the ancient tensions between Athens and

Eleusis during the historical period. It is through

cult ritual that this conflict is resolved, and so the west pediment presents the origins of cult practice within the sanctuaries

of Athena Polias at Athens and of

Demeter and Kore at Eleusis. Eumolpos plays a pivotal role in founding the

Eleusinian Mysteries, serving as one of the first priests of Demeter and Kore. A clan named the Eumolpidai held the special privilege of providing Eleusinian priests throughout the historical period.

Kekrops, father of the

Athenian royal line, is, as we’ve said, king during the contest between Athena and Poseidon. At the north side of the pediment we find him kneeling, a snaky coil beneath his left knee signaling his earthborn origins (below). Wrapping her arm around her father from behind is one of his three daughters, probably

Pandrosos. Her two sisters, Aglauros and

Herse, sit farther to the right, as known only from the Nointel drawings. The crayon sketches (insert

this page

, right)

also show a young boy leaning across their laps, no doubt Erechtheus/

Erichthonios, who came into their care following his gegenic birth.

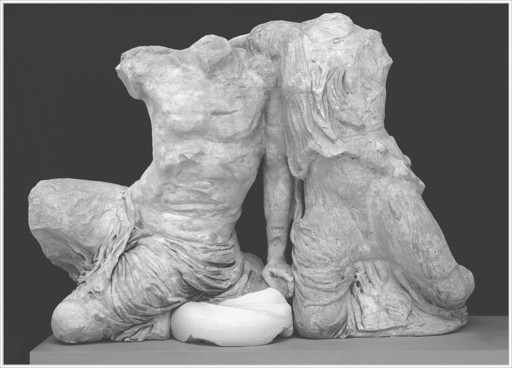

Kekrops and Pandrosos, west pediment, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.38

)

At the opposite end of the gable we find a parallel arrangement for the

royal house of Eleusis.

90

Here, we see Queen

Metaneira, wife of King

Keleos, with her three daughters, said to be named

Diogeneia,

Pammerope, and

Saisara.

91

And here, too, we find a young boy stretched across the laps of the maidens, no doubt the child

Triptolemos, who was looked after by the Eleusinian princesses just as Erichthonios was by the daughters of Kekrops. And so, we observe a perfect

genealogical symmetry, with two sets of three royal daughters, one at Athens and the other at Eleusis, each set with a boy to nurse. And just as the daughters of Kekrops perform special rites for their local goddess,

Athena, so, too, the daughters of Keleos perform sacred offices for

Demeter and Kore in the

Eleusinian Mysteries.

92

Religious practice of the historical period is thus explained through the charter myths of the ancestors, the founders of the cults that survive for nearly a thousand years at Athens and Eleusis.

IT BECOMES APPARENT

that we cannot understand the Parthenon or the

Athenians themselves outside the sphere of

religion. This is true of the

birth of democracy, too. Indeed, the novelty of democratic rule would not have been conceivable without the intense

awareness

of the common bond forged by shared genealogy as fostered by religion. The nexus between the cosmology that defined Athenian consciousness and the unique civic life that these people created for themselves is not only revealed but exalted in that epitome of Athenian self-awareness, the Parthenon. To this extent the Parthenon celebrates democracy, but not on the terms that have been suggested since the Enlightenment. And perhaps not even on the terms that obtained in Athens by the age of Perikles.

When we marvel today at the extraordinary triumph of engineering, architecture, and aesthetics that endures on the Sacred Rock, it is hard to fathom that anyone could have opposed its creation in the first place. But Plutarch tells us it was this more than any other of Perikles’s endeavors that his enemies maligned and slandered. In the assembly, they shouted that Athens had lost its good name in the disgraceful transfer of the common fund from Delos to the Acropolis. “The Greeks regard it as outrageously arrogant treatment, as blatant tyranny, when they can see that we are using the funds they were forced to contribute for the military defence of Greece,” critics cried.

93

Indeed Perikles’s excuse about safeguarding the treasure was only a ruse to spend it on his own extravagant enterprise. Squandering the compulsory contributions of the confederation, Perikles and his supporters were now, it was charged, “gilding and decorating the city, which like a wanton woman, adds to her wardrobe precious stones and costly statues and temples worth their millions.”

94

The

Athenian Empire was not only flexing its muscles but covering them in purple.

Not that the effort lacked admirers. Plutarch, for his part, could only marvel at how such magnificence and permanence of construction had been wrought so fast.

This is what makes Perikles’ works even more impressive, because they have durability despite having been completed quickly. In terms of beauty each of them was a classic straight away at the time, but in terms of vigour each is a new and recent creation even today; and so a kind of freshness forms a constant bloom on them and keeps their appearance untouched by time, as if they contained an evergreen spirit and an unaging soul mingled together.

Plutarch,

Life of Perikles

13

95

But it is Thucydides who has the final word, looking into the future with uncommon prescience. He foresaw that the marble summit of the Acropolis would live on through the ages, giving the impression that the Athenians were even greater than they were. The lasting spectacle of its soaring marble, exquisitely hewn, would, in future, eclipse any of rival Sparta’s achievements:

For if the city of Lakedaimon [Sparta] were to become desolate and nothing of it left but temples and foundations of buildings, I think as time went by future generations would believe her fame to be greater than her power was. And yet, the Spartans occupy two-fifths of the Peloponnese and lead the alliance, not to speak of their numerous partners abroad. Still, as their city is scattered near and far and lacks magnificent temples and public buildings, spread out as it is in villages

after the old fashion of Hellas, their power will seem inferior. But if the same things happen to Athens, one will think by the sight of their city, that their power was double what it is.

Thucydides,

Peloponnesian War

1.10.2

96

Thus, over the course of the fifth century, a new

Athenian identity emerges, one carefully constructed to glorify Athens and incite fear in the hearts of its enemies. The trappings (and overreach) of empire continued to bloat Athenian self-regard.

97

Still, it must be said that the picture that Athens consistently projected of itself—in funeral orations, speeches in the law courts, dramatic

performances, and the sculptures of the Parthenon—stands in contrast to the self-image expressed by other cities. We continually hear from the Athenians about their exceptionalism, how they are resilient, persistent, competitive, aggressive, quick but thoughtful in action, innovative, aesthetically aware, and open to engaging outsiders on the world stage. And many non-Athenians accepted this characterization. Perhaps no words capture it more powerfully than those Thucydides attributes to the Corinthian envoys who addressed the first

Spartan congress in 432

B.C.

On the eve of the Peloponnesian War, the Spartans summoned members of the

Peloponnesian League (especially those with grievances toward Athens) to testify before the Spartan assembly. The Corinthians were gravely worried by the Athenians’ alliance with their former colony, now enemy,

Kerkyra (Corfu), a pact signed in 432

B.C.

amid the

Corinth-Kerkyra War. Combining its great naval might with Kerkyra’s (as well as with that of Rhegium in southern Italy and Leontini in Sicily, according to alliances forged in 433/432), Athens would soon be in a position to threaten trade routes, especially those that carried shipments of grain from the west. This was of critical concern to all Peloponnesians, especially to the landlocked Spartans, whom the Corinthians considered far too complacent for their own good. The ambassadors stressed the growing cause for alarm and pulled no punches in contrasting the natures of the Athenian and the Spartan peoples:

You have never considered what manner of men are these Athenians with whom you will have to fight, and how utterly unlike yourselves. They are revolutionary, equally quick in the conception and in the execution of every new plan; while you are conservative—careful

only to keep what you have, originating nothing, and not acting even when action is most urgent. They are bold beyond their strength; they run risks which prudence would condemn; and in the midst of misfortune they are full of hope.

…They are impetuous, and you are dilatory; they are always abroad, and you are always at home. For they hope to gain something by leaving their homes; but you are afraid that any new enterprise may imperil what you have already. When conquerors, they pursue their victory to the utmost; when defeated, they fall back the least. Their bodies they devote to their country as though they belonged to other men; their true self is their mind, which is most truly their own when employed in her service.

Thucydides,

Peloponnesian War

1.3.70–71

98

One can only imagine the emotional effect of such a speech on the Spartans who listened.

99

As

Josiah Ober has shown, Spartan culture had long aimed to instill a deep-seated code of conduct among its soldier citizens. Behavior contrary to its norms was simply unthinkable under Sparta’s military oligarchy. As we have seen, Athens, too, had a code of sorts, one well summarized by the words Thucydides attributes to the Corinthians: “Their bodies they devote to their country as though they belonged to other men; their true self is their mind, which is most truly their own when employed in her service.” It was this delicate balance of individualism and the polis, the citizen’s utter devotion, uncompelled, to its good, that made Athens unique, even before its

radical democracy, which perforce created certain possibilities and dynamisms other political systems could not sustain. Of course, Thucydides is writing as an Athenian and as one of Perikles’s greatest admirers. But whether these words truly came from Corinthian lips or no, there is a truth to them.

Nowhere is this belief more powerfully expressed than in that most famous of Greek orations, the eulogy Perikles delivered in the autumn of 431 at the end of the first season of the Peloponnesian War. Just a year after the Corinthians’ address to the Spartan assembly, war had indeed broken out as feared, and now Perikles stood in the public cemetery (

demosion sema

,

this page

) addressing the families of the fallen and the citizenry as a whole. This is what Thucydides tells us he said, honoring the first Athenians to die: