The Parthenon Enigma (27 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

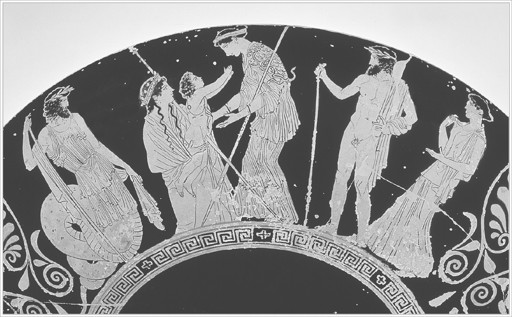

Ge rises from the earth to hand the baby Erichthonios to Athena while Kekrops, with the tail of a snake, watches at left; Hephaistos and Herse (?) stand at right. Cup by Kodros Painter, 440–430 B.C. From Tarquinia. (illustration credit

ill.43

)

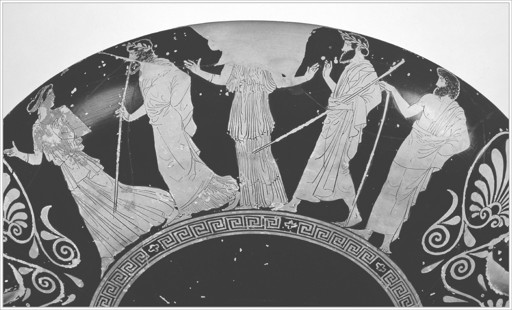

Aglauros and King Erechtheus (with scepter) at left; Pandrosos at center; Aigeus and Pallas (?) at right. Cup by Kodros Painter, 440–430 B.C. From Tarquinia. (illustration credit

ill.44

)

Greek myth is an ever-changing phenomenon that “morphs,” as George Lucas would have it, into new and sometimes contradictory versions with each retelling. There is no correct or better version of any myth, just as there is no “wrong” recounting of these tales. Their transformative nature forces upon the modern audience a frustrating, even unsettling level of ambiguity, a theme to which we shall return. Suffice it to say, our heroes Erechtheus and Erichthonios are hopelessly intertwined, their stories woven together by each other’s myriad adaptations spanning hundreds of years. What remains indisputable, however, is

that Erechtheus is the only name given to the defining king

of Athens. He is known as such from his very first appearance in the

Iliad

. Erechtheus alone is the recipient of a cult in a temple called the

Erechtheion, not the Erichthoneion. Athens is called the land of Erechtheus, never the land of Erichthonios. Likewise, the

Athenians were always the “Erechtheidai” and at no time the “Erichthoniadai.”

36

To be sure, our appreciation of Erechtheus has been muted over the years, not by his lack of importance, but by the vicissitudes of surviving material evidence. It doesn’t help matters that he has sometimes been outshone by another legendary king, Kekrops, who

Herodotos tells us reigned a generation earlier.

37

This too is a pair that presents distracting similarities. Both Kekrops

and Erechtheus/Erichthonios are associated with autochthony and the establishment of Athenian cult. In art, Kekrops is depicted with serpent legs (

this page

) and Erechtheus/Erichthonios is often shown with snakes.

38

Most tellingly, each has three daughters, two of whom come to a terrible end, by some accounts leaping to their deaths from the cliffs of the Acropolis.

Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood has argued persuasively that Kekrops is in fact a transformation of Erechtheus. She sees the former’s persona as governed by “an intensification and emphasis on the element of autochthony,” hence his depiction with a snaky tail.

39

We do well to reconcile ourselves to the dynamic complexity of Athenian foundation myths over the

longue durée

, in all their richness of projection, transference, and contamination.

Still, it remains that Erechtheus is the first Athenian king to be mentioned in Greek literature, present already in

Homer at the turn of the eighth to the seventh century

B.C.

His rise to prominence in mid-fifth-century Athens, a reawakening of the sleeping hero, so to speak, seems intricately bound up with the vision of

Perikles and his efforts to renew the Acropolis temples. In the wake of the

Persian Wars and the collective trauma suffered by the Athenians, what better than to go back to the very beginning, to the oldest founding father and the founding principles upon which the city had been built. Erechtheus was the man for the moment, a hero whose family tragedy embodied the very spirit of self-sacrifice so emphatically projected by the Periklean democracy.

Of irreducible significance is that, without Athena,

Hephaistos’s seed would never have been spilled upon the earth and Erechtheus would never have been born. Indeed, while Athena remains a virgin goddess, she is, in a very real sense, the genitor of Erechtheus and, therefore, of

all Athenians. In this sense, Erechtheus can and must be understood as later championing the cause of his “mother,” Athena, just as

Eumolpos avenges the defeat of his father,

Poseidon.

After Athena wins the primordial contest for patronage of Athens, tensions with Poseidon persist. The gods’ mortal issues, Erechtheus and Eumolpos, continue the rivalries of their respective parents, Eumolpos reigniting hostilities when he bands an army of Thracians from northeastern Greece to settle the score for his father.

40

Thucydides tells us that in days of old when towns were independent of the Athenian king, they sometimes made war upon him “as did Eumolpos and the Eleusinians against Erechtheus.”

41

Hearing of the impending siege, King Erechtheus consults the

oracle at Delphi to learn how he can stop Eumolpos. The answer is devastating: the king must sacrifice his daughter to save the city. Erechtheus shares the bad news with his wife, Praxithea, asking her leave to let their daughter die. The queen answers with that rousing, patriotic speech we examined in

chapter 3

.

Lykourgos is clearly confident of the power of those lines to stir the Athenian heart even a hundred years after they were first performed, advising the gentlemen of the jury: “You will find in them a greatness of spirit and a nobility worthy of Athens and a daughter of the Kephisos.”

Emboldened by his wife’s ardor, Erechtheus sacrifices their youngest daughter, a nameless girl simply called “Parthenos,” or “Maiden,” throughout the play. The names of the daughters of Erechtheus and Praxithea are greatly confused in the ancient sources, with conflicting lists given by various authors over several hundred years.

42

Later authors speak of four and even six daughters of Erechtheus, as well as several sons.

Phanodemos names

Protogeneia and

Pandora as the sisters who died (to save Athens from Boiotian, not Thracian, attack) while giving the names

Prokris,

Kreousa,

Oreithyia, and

Chthonia for the surviving daughters.

43

Apollodoros names Prokris, Kreousa, Oreithyia, and Chthonia and, interestingly, lists a son named Pandoros as well as two others named Kekrops and

Metion II. He has Chthonia as a survivor who goes on to marry

Boutes.

44

But

Hyginus says that Chthonia is the girl who was sacrificed (to Poseidon) and that the other girls killed themselves.

45

Yet he also names Aglauros as a

son

of Erechtheus by another of his daughters, Prokris—never mind that Aglauros is regularly identified as the

daughter

of Kekrops.

46

In the great tangled web that is Attic myth,

the most potent configurations replicate themselves: in the three daughters

of Erechtheus we see the same pattern evident in

chapter 1

with the three daughters of Deukalion and the three daughters of Kekrops.

47

And there are of course connections: both Deukalion and Erechtheus have a daughter named

Pandora, while Kekrops has a daughter named

Pandrosos. More than likely we are seeing a Pandora/Pandrosos substitution in the same manner as Erechtheus/Erichthonios.

48

The battle ensues, and as promised by the oracle, the Athenians are victorious. But, in a turn of events that

Praxithea did not anticipate, Erechtheus is killed, swallowed up in an earthquake caused by

Poseidon. As for the two older daughters, we learn that they kept their oath that if one of them should die, the others would die as well. The surviving fragments of the

Erechtheus

do not explicity tell us how the sisters die, but there may be some suggestion that they leaped off the Acropolis in a suicide pact. Though the text is very uncertain here, lines apparently spoken by Praxithea seem to address the two daughters whose bodies may lie before her.

49

This would concur with the account given in

Apollodoros which says that following the sacrifice of the youngest daughter, the two remaining sisters killed themselves.

50

It should be remembered that later writers, including Apollodoros, ascribe death by suicidal leap to another pair of royal daughters, those of King Kekrops, who ruled a generation before Erechtheus.

51

Having looked into a forbidden box containing the baby Erichthonios and a snake, the sisters Aglauros and

Herse were driven mad and jumped from the Acropolis or, in an alternative account, into the sea.

52

Aspects of Athenian myth are thus transferred between different sets of royal sisters so that even within the corpus of a single author the same triad might be disposed of in different ways. In his play the

Ion

, first performed in 414–412

B.C.

, some years following the

Erechtheus

, Euripides clearly states that

three

daughters of Erechtheus were sacrificed.

53

The boy Ion asks his mother,

Kreousa (understood to be the youngest sister of three girls, apparently just a baby and too young to be killed when the others were sacrificed), “Is it true, or merely a tale, that your father killed your sisters in sacrifice?” Kreousa replies, “He dared to kill his maiden daughters as sacrifices [

sphagia

] for this land.”

What is important here is that the two older daughters of Erechtheus kept their pledge and died, either by the hand of their father or by their own devices. While Queen Praxithea thought that she was giving just

one child to die on behalf of all, she in fact loses all three daughters and her husband, a far greater sacrifice than she could have imagined.

The discovery of the new fragments of the

Erechtheus

, peeled from the mummy brought to Paris by

Pierre Jouguet, is nothing short of momentous for the clarity of understanding it brings to the temples standing on the Acropolis today. For the first time ever, we can read the words

Euripides gives to

Athena, as spoken to Queen Praxithea toward the very end of the play, when she stands alone on the Acropolis, having lost her entire family. The goddess delivers what can be described as a divine charter for the construction of the two great temples on the Sacred Rock: the Parthenon and the

Erechtheion. Athena first instructs Praxithea to bury her daughters in the same tomb, over which she is to build a sanctuary, establishing sacred rites in their

memory. She then directs the queen to bury her husband in the middle of the Acropolis and to erect a sacred precinct for him. Finally, Athena names Praxithea as her priestess and entrusts her with the care of these holy places. Only Praxithea will have the right to make burnt sacrifice on the

altar of Athena that serves both tomb-shrines (

this page

). Fascinatingly, Athena’s speech employs language well known from

sacred laws (

leges sacrae

), texts inscribed in stone to decree cult practice, including the construction of temples within Greek sanctuaries.

54

It now becomes clear just how aptly this naiad nymph, daughter of the Kephisos, is named. “Praxithea” is a compound of the roots

prasso

(“to perform”) and

thea

(“goddess”), and so the name means, quite literally, one who does things for the goddess. She is Athena’s ideal priestess: noble, selfless, and strong. It is relevant here that the historical

priestess of Athena Polias who served on the Acropolis at exactly the time the

Erechtheus

was first performed was a woman of exceptional power and character. Her name was

Lysimache, and she was daughter of

Drakontides of Battae, sister of

Lysikles, the treasurer of the Athenians. Lysimache held the priesthood of Athena Polias for an impressive sixty-four years (spanning the last decades of the fifth century as well as those of the early fourth). It is very possible that Euripides had this well-known city official in mind when he constructed the potent and patriotic character Praxithea for his

Erechtheus

.

55

Aristophanes certainly had Lysimache in mind when he wrote the leading role for the heroine

Lysistrata in his famous comedy of that same name, first performed in 411

B.C.

56