The Parthenon Enigma (8 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

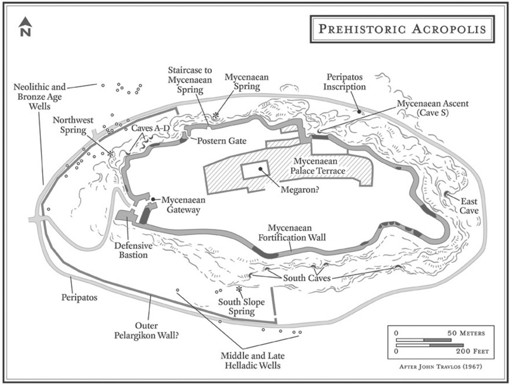

Down below, at the foot of the Acropolis and encircling its entire western end, a second circuit wall may have been constructed, giving additional protection to the citadel’s entrance and water sources. It is believed to have run from just west of the Mycenaean Spring, on the

north, to just east of the South Spring, the site of the later Asklepieion, at the south of the Acropolis (below).

87

Ancient sources refer to this wall both as the

Pelargikon, the “Place of the Storks,” and as the Pelasgikon, named for the

Pelasgoi, the pre-Greek inhabitants of Athens about whom we know very little.

88

Whoever built the walls atop and around the Acropolis at the end of the

Bronze Age, the sheer size of these fortifications points to the severity of the perceived threat. But absence of evidence of burning or destruction on these walls suggests they worked

well and may never have been breached, that is, until the Persian assault nearly eight hundred years after they were built.

The Mycenaeans made brilliant use of a natural cleft along the north face of the Acropolis, gaining access to the water-rich levels beneath.

89

A vertical fissure some 35 meters (115 feet) deep was caused when a great chunk of bedrock sheared off the Acropolis and came to rest parallel to it. Around 1200

B.C.

, a staircase of eight flights was built down the narrow corridor. Cuttings in the rock held wooden steps leading all the way down; the lower courses had treads of stone resting upon the wood, all slotted into notches within the rock face. At the base of the staircase, a circular well shaft descended a further 8 meters (26 feet) through the underlying marl to create a reservoir. Ex

cavators have designated this construction the “Mycenaean Spring” (previous page). Though used for only about twenty-five years before it collapsed, it nonetheless provided a secure water source at a time when early Athenians were under threat of attack.

90

Prehistoric Acropolis. (illustration credit

ill.10

)

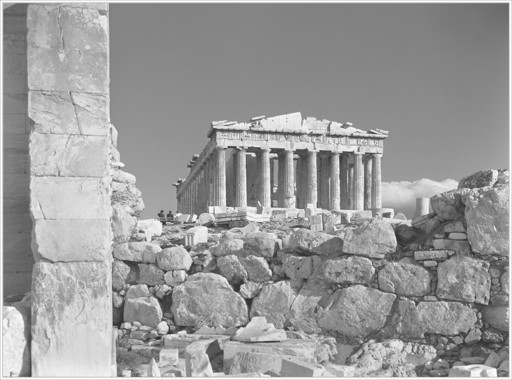

Parthenon with Mycenaean wall in foreground, from west. (illustration credit

ill.11

)

Seven hundred years later, around 470–460

B.C.

, an impressive

fountain house was built atop a spring some 90 meters (300 feet) to the west of the Mycenaean Spring, there on the north slope of the Acropolis (labeled Northwest Spring on previous page).

91

It is likely to have been the statesman

Kimon who initiated construction of this springhouse at the same time he bolstered the fortification wall at the south side of the Acropolis. The Kimonian fountain house was set within the rocky overhang of a cave that gives access to the flowing water deep beneath; very special care was taken to maintain the original, rustic appearance of the craggy setting. First used during the Neolithic period,

92

the Northwest Spring is likely to be that associated with the nymph

Empedo, whose name means “firmly set” or “in the ground”; indeed, its water source is so deep that inlets leading to its draw basin sit 6 meters (20 feet) below ground level. A boundary inscription found nearby in the Agora and

dated to the first half of the fifth century speaks of the

Numphaio hiero horos

, “the boundary of the sanctuary of the Nymph.”

93

This has been taken to mean the nymph Empedo.

In time, this spring comes to be known as Klepsydra (literally, “Water Hider”), owing to its remote location, hidden within the rocky cliffs.

94

It was an important resource for the people of Athens, especially since a number of preexisting wells in the area had been filled with debris and put out of use during the late sixth and early fifth centuries. With the introduction of the Klepsydra fountain in the 460s, the north slope of the Acropolis was made more accessible to visitors, a very different state of affairs from in the Archaic period and earlier, when the precious water sources were guarded behind walls.

95

This marks an important shift in the function of the north slope, no longer just a source of secure and plentiful water but a place of shrines, worship, and visitation. In a very real sense, this evolution into a place of commemoration and devotion marks the

expansion of the sacred space of the Acropolis down its slopes and the opening up of the Sacred Rock to the larger community. This development harmonizes with the new democratic spirit sweeping Athens, a process that will culminate, decades later, with the erection of its greatest temple, the Parthenon.

TODAY, AS IN ANTIQUITY

, a path circles the Acropolis, roughly halfway up its slopes. This enables visitors to circumnavigate the Sacred Rock and to visit the host of caves and crags that came to be used as sacred places. During the mid-fourth century, someone carved into the bedrock along the northern stretch of this pathway an inscription giving its name and length: “The

Peripatos, five stades and eighteen feet.”

96

This measures some 893 meters, or just over half a mile. The inscription can be seen to this day, just east of the sanctuary of

Aphrodite and Eros, more than halfway around the northern face of the Acropolis as one approaches its east end (

this page

). Since 2004, the Peripatos walkway has been reopened to the public, affording the great pleasure of viewing the city from above while walking a wilderness landscape, right in the heart of Athens. Strolling the Peripatos and visiting its caves, crags, springs, and lush vegetation bring viewers as close as one can get to an ancient experience of the natural environment.

Roughly a dozen caves penetrate the rocky slopes of the Acropolis,

and over time at least half of these came to be regarded as sacred. The

caves of

Apollo,

Pan, and the

nymphs, together with the sanctuaries of

Aphrodite, Aglauros, and

Asklepios positioned on rocky ledges near caves, claim special

places of memory here amid the cliffs.

97

All across Attica, some twenty-eight sacred caves have been identified. Athens is the only city that allowed cave sanctuaries within the limits of its urban area for easy access to the experience of a rustic, sacred landscape setting.

98

In this, we may perceive the intensity of Athenian religiosity, an urgent desire to connect with the

prehistoric cave dwellers, the Neolithic ancestors who may have made their homes within these rock shelters. Let us visit these caves, starting at the northwest shoulder of the Acropolis and at an elevation of some 125 meters, or 410 feet, above sea level. Here, high above the

Klepsydra fountain, we find a broad level shelf that opens onto four further caves, designated A–D (below and

this page

).

Cave A sits farthest to the west, shows a low rock-cut bench, and is of unknown use. Cave B was sacred to Apollo, and Cave D was sacred to Pan. Cave C has been assigned to Zeus, but not all scholars agree.

The shallow rock shelter known as Cave B, second from the west, was among the most famous settings in all of Athenian myth (facing page). Long identified as the shrine of

Apollo Hypo Makrais, “Apollo Under the Long Rocks” or “Apollo Below the Heights,” this is the spot where the god is said to have forced Kreousa, daughter of King Kekrops, to make love to him. From this union, the child Ion was conceived. Having given birth in secret, Kreousa hides her shame by leaving the infant wrapped in swaddling clothes, here in the same cave where she had lain with the god.

99

Apollo intervenes, instructing the god Hermes to rescue his son and carry him to Delphi. At the Delphic sanctuary, Ion was educated by a priestess of Apollo and served as a temple boy within the shrine of his father.

100

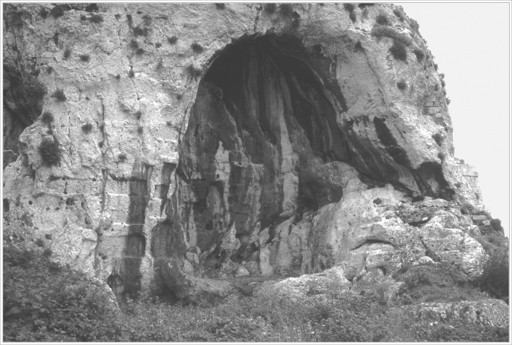

Acropolis, north slope, Caves A–D, from northwest. (illustration credit

ill.12

)

Cave of Apollo Hypo Makrais (Cave B), from the north. (illustration credit

ill.13

)

As we know from

Euripides’s play, named the

Ion

after the youth,

Kreousa later marries

Xouthos, with whom she finds herself unable to conceive a child. The pair travel to

Delphi to seek the oracle’s advice. After a series of misunderstandings and the subsequent revelation of hidden identities, Kreousa is reunited with Ion and recognizes him as her son. Ion grows up to marry

Helike, daughter of King Selinos of

Aigialeia (and thereby granddaughter of

Poseidon), and establishes a city named Helike for her in Achaia on the north coast of the Peloponnese. Here,

Poseidon Helikonios was worshipped well into the Roman period.

101

The children of Ion and Helike, and their descendants forever after, were called

Ionians, and thus our hero establishes what comes to

be known as the Ionian race. Through this myth the Athenians were able to claim kinship with their Ionian neighbors in East Greece, strategically emphasizing this cultural connection when seeking Ionian support during time of war. Importantly, Ion himself led an expedition, with the help of the Athenians, against their longtime enemy,

Eleusis. He lost his life in this battle, just outside the sanctuary of

Demeter and Kore.

The cave of

Apollo Hypo Makrais has been explored and studied by archaeologists from the late nineteenth century on.

102

Over a hundred niches have been cut into its rock walls and onto the spur that separates it from Cave C.

103

In fact, human activity is evidenced here from as early as the thirteenth century

B.C.

The myth of

Kreousa and Apollo may be evocative of Neolithic times when the

prehistoric populations of Attica lived in just such rock shelters and deep caves. Here, the earliest inhabitants of what would become Athens made new families that went on to become great ones, just as we have seen with Ion. Safeguarding and remembering the rock shelters of primitive days, set close to the opulence of the Parthenon and other lavishly built Acropolis structures, would keep something of the remote past near at hand. These

places of memory were constant reminders to the Athenians of their rustic origins.