The Parthenon Enigma (7 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

Like all rivers, the Kephisos was understood to be the child of

Okeanos, the freshwater river that encircled the earth, and his wife,

Tethys, a sea goddess whose name means “Nurse.”

62

By some accounts, the Kephisos had a daughter named

Diogeneia, who gave birth to the naiad nymph

Praxithea. (The word “naiad” comes from the verb

nao

, “to flow,” and refers to river

nymphs.) By other accounts, Praxithea is the daughter, rather than the granddaughter, of the Kephisos.

63

In any case, Praxithea marries King

Erechtheus of Athens, a union that follows a well-attested pattern by which naiads wed local kings and play

prominent roles in local genealogies. The maiden

Oreithyia (she who was abducted by the North Wind along the Ilissos, as discussed by

Sokrates and

Phaidros) was a daughter of Praxithea and, thus, a granddaughter (or great-granddaughter) of the Kephisos. And so we find the royal family of Athens descended directly from its greatest river and his nymph daughter. As a naiad, Praxithea nurtures her family, providing the wetness necessary for the germination of seed, ensuring fecundity, growth, and prosperity in the royal line. In this, she follows a model in which naiad nymphs, as mothers of the city, protect the community’s all-important

water supplies that come from local springs and streams.

According to

Apollodoros, Praxithea had a nymph sister,

Zeuxippe, who married King

Pandion of Athens in a similar arrangement. Zeuxippe gave birth to two daughters,

Prokne and

Philomela, and twin sons,

Boutes and Erechtheus.

64

This is the same Erechtheus who goes on to marry Praxithea, his mother’s sister.

Hyginus names Zeuxippe as daughter of the

Eridanos River.

65

It can be difficult fitting various versions of

myths, recounted for different purposes and across many centuries, into comprehensive genealogies, and there is no avoiding repetition and contradiction. Compilers of myth variants, working centuries later than the first telling of the tales, created anthologies filled with inconsistencies.

66

Mythmaking is an ever-dynamic process with no definitively “right” or “wrong” version, though a force akin to natural selection seems to exert itself on the crucial features.

The Eridanos (“Morning River” or “River of Dawn”) is the shortest of the Athenian rivers, rising from the slopes of

Mount Lykabettos and coursing southwestward to skirt the north side of the Agora.

67

Wastewater and torrential overflows from the ancient marketplace were, by the end of the sixth century

B.C.

, guided into the Eridanos through a stone channel that has been designated by its excavators as the “Great Drain.”

68

When the politician and general

Themistokles built new fortifications for Athens following the

Persian destruction of 480, the Eridanos was enclosed in a stone-lined channel directing its flow out beyond the Dipylon, the “Double Gate,” and through the Kerameikos cemetery.

Athenians had begun to bury their dead along the banks of the Eridanos very early, by the end of the twelfth century

B.C.

One hundred sub-Mycenaean graves have been found on the north side of the river and a few on the south bank. During the tenth century there was a shift, and the south bank was increasingly used for burials. By the Archaic period,

that is, roughly, from the turn of the seventh to the sixth century

B.C.

, the main necropolis was firmly established here. It became known as the Kerameikos cemetery owing to its proximity to an industrial area where

potters (

keramei

) worked their kilns firing ceramics for the city (

this page

).

69

The Eridanos may have been regarded as a kind of river of

Hades and, like the river

Styx, a stream to be crossed on one’s journey to the underworld.

70

THE THIRD RIVER

of Athens, the Ilissos, flows from

Mount Hymettos at the northeast of the city, circling down and around to the south of the Acropolis. As recently as the 1950s, the river could be seen at the foot of the Panathenaic Stadium, known as the Kallimarmaro, or “Beautifully Marbled.” In myth, Ilissos was understood to be the son of the sea god

Poseidon and the earth goddess

Demeter. A child of the land and the sea, the Ilissos was a vital player in local ecosystems and home to a host of shrines. The spot sacred to Acheloös and the

nymphs referenced in the

Phaidros

was on the river’s east bank at the foot of the

Ardettos Hill (

this page

). About 500 meters (0.3 mile) downstream, on the west bank, rises the

spring known as Kallirrhöe. Today, it is just a faint rivulet falling beside the little church of Agia Photini, but early on the area was so marshy that it was called Vatrachonis (“Frog Island”).

71

This mere trickle of water is likely to be one and the same as the great spring Kallirrhöe that Thucydides claimed to be the main source for water for the early city.

72

With the building of a formal

fountain house over it, the place became known as Enneakrounos, or “Nine-Headed,” for the nine spouts built to facilitate collection, and eventually becomes the preferred spot for Athenian brides to take their nuptial baths.

73

Just opposite the spring, on the banks of the Ilissos, sits a little

shrine of Pan. His image can be seen to this day, carved into the rock face of a surviving wall, a lone reminder of devotions practiced on this spot in the ancient past.

74

Kallirrhöe was the daughter of

Okeanos and

Tethys, who, according to

Hesiod, produced a total of forty-one nymph daughters who protected girls and maidens just as

Apollo and the rivers protected boys and youths.

75

By one account, Kallirrhöe mated with

Khrysaor, son of

Medousa, and gave birth to a terrible three-bodied giant known as

Geryon, eventually killed by

Herakles. In the sixth century

B.C.

the poet Stesichoros wrote a

Song of Geryon

that celebrated the conflict of

the giant and the hero, a fight in which

Poseidon sided with his monstrous grandson while

Athena protected her favorite, Herakles.

76

This conforms to a pattern that will become familiar, one in which Athena and Poseidon battle each other through proxies. By some later accounts, Kallirrhöe mated with Poseidon and gave birth to

Minyas, founder and king of

Orchomenos in Boiotia.

77

The relationship between Poseidon and

spring nymphs was always a delicate one. Should he become angry with them, he can withdraw his water and cause their

springs to go dry.

On the southeast bank of the Ilissos, just opposite Kallirrhöe, stretches the area known as

Agrai (

this page

). Fittingly, we find

Artemis here, worshipped in the marshy, wild, and wooded setting that she so favored.

78

In this precinct, the goddess was called by the cult name Agrotera, “the Huntress,” just as she was at Marathon, where she helped the Athenians defeat the Persians in 490

B.C.

The wetlands of Marathon Bay and the marshy plain to the west of it where the battle was fought represent exactly the kind of terrain in which Artemis is happiest. So, too, here on the swampy banks of the Ilissos,

Artemis Agrotera finds a home.

Foundations of a small

Ionic temple, probably erected around 435–430

B.C.

, sit on a rocky knoll positioned just above the south bank of the river, roughly opposite the spring of Kallirrhöe (

this page

).

79

These belong to the temple of Artemis Agrotera, the setting for one of the most exceptional

sacrifices in the Athenian

festival

calendar. Before the battle at Marathon the Athenians vowed that they would sacrifice to Artemis Agrotera one goat for every Persian killed. This was in accordance with a long tradition of prebattle sacrifices (

sphagia

) offered to deities in hopes of a favorable outcome.

80

When an astounding 6,400 Persians were killed at Marathon (to Athens’s loss of just 192 men), the Athenians were unable to find enough goats to make good on their promise. So it was decreed that forever after six hundred goats would be sacrificed annually in fulfillment of the vow. This sacrifice was offered each year on the anniversary of the battle, the sixth day of the month Boedromion, in our early September. It was observed at least into the first century

A.D.

81

Not many

rituals could have impressed themselves on the consciousness of the Athenians with the same force as seeing six hundred goats led to the banks of the Ilissos for sacrifice every year.

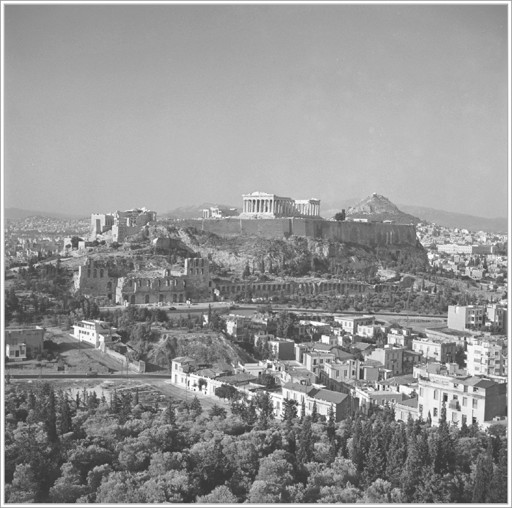

AS WE RETURN

to the city’s beginnings, we reflect on how beautifully situated Athens is, set far enough inland that it could be easily defended yet close to a series of excellent harbors (some 6 kilometers, or 3.7 miles, to the south) that link it to the wider world. Of all the hills that the early settlers could have chosen for their acropolis citadel, they decided not on the highest peak but on that which had the best water source. The Acropolis, which rises to a height of 150 meters (500 feet), was the most promising among a number of candidates. Steep cliffs gird it on three sides, leaving only one point of easy access on the west and rendering it more easily defensible from enemy assault. Though

Mount Lykabettos, to the north, is the highest hill in Athens at 277 meters (909 feet), it lacks the all-important combination of water, natural defenses, and a summit that could be easily leveled, elements that made the Acropolis so attractive to early city builders (below).

Many city-states across Greece were founded on

acropolis citadels.

But few could boast an acropolis rock as prominent as the Athenian. It rises abruptly from the surrounding lowlands and, throughout the city, is never lost to view. This bare, stark “bunker” of limestone, encompassing an area of just 7.4 acres, has persisted as the focal point of Athens from the fourth millennium

B.C.

to the present (previous page and insert

this page

).

82

View of the Acropolis from the southwest with Mount Lykabettos in the distance. © Robert A. McCabe, 1954–1955. (illustration credit

ill.9

)

The well-watered slopes of the Acropolis’s northwest shoulder were as suited to times of peace as to those of siege. Here, twenty-two shallow

wells have been discovered dating to the Late Neolithic period (ca. 3500–3000

B.C.

), when they would have provided water for inhabitants who, presumably, lived nearby.

83

For reasons that remain unclear (perhaps a drought from climate change, decimating the population), these wells were abandoned during the millennium that followed. It is not until the Middle

Bronze Age (ca. 2050–1600

B.C.

) that new wells were dug along this same slope, as well as to the south of the Acropolis. At the same time houses were built on the south slope and, possibly, also on the summit. Graves for

children have been found atop the Acropolis and more tombs and graves to the south.

84

The water-rich veins running through the Acropolis rock result from its geological formation, in which porous limestone overlies a layer of calcium carbonate marl, the uppermost part of the so-called

Athens Schist.

85

Rainwater filters down through cracks in the limestone until it meets and gathers atop the marl. Since the geological stratigraphy of the Acropolis tilts from high at the southeast to low at the northwest, water trapped atop the marl level drains down to the west end, emerging in a series of natural

springs.

A Mycenaean palace was built atop the Acropolis sometime between 1400 and 1300

B.C.

(facing page).

86

By 1250, the citadel was protected by massive fortification walls, stretches of which survive to this day. They stood as high as 10 meters (33 feet) and, in some places, were 5 meters (16 feet) thick. These walls are constructed in the so-called Cyclopean masonry style in which huge unworked stones were piled one atop another (

this page

), so huge that it was believed only giant

Cyclopes could have lifted them into place.