The Parthenon Enigma (6 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

While man-made groves and gardens adorned the metropolitan environment, it was tracts of land left wild that brought something of the countryside into the city’s reach. Just a short walk to the southeast of the Acropolis, outside the city walls and on the banks of the Ilissos, was a marshy, wooded area known as

Agrai, literally “Wilderness” or “Hunting Ground” (

this page

).

39

Damp with wetlands and uncut vegetation, this was a refuge for

waterfowl, game birds, and other small animals. Just minutes from the Acropolis, Agrai was easily accessible for urbanites wishing to hunt and fish. It was also an area bristling with shrines and sacred landmarks commemorating past encounters between mortals and the divine. Local place-names reflect this landscape:

Dionysos in the Marshes (Limnai),

Artemis the Huntress (Agrotera), the Mother in the Wilderness (Metroon in Agrai).

40

So, too, the slopes of the Acropolis itself were (and still are) rich with natural microenvironments: caves,

springs, rocks, crags, and brambles that served as the setting for the most venerable tales from the city’s distant past.

THAT SO MANY

of these

places of memory should have to do with water should come as no surprise. In words attributed to the sixth-century philosopher

Thales of Miletos, “water sustains all.”

41

This certainly was the case for Athens, where the life-giving power of ancient sources bound generations of citizens to the same places: springs, lakes, pools, rivers, streams, marshes, caves, and watery crevices were places to which local inhabitants flocked for respite from the Mediterranean heat and to quench their thirst. Over time, wells and

fountain houses were built atop natural springs to capture the gush of potable water. They became central meeting places for the community and one of the few destinations to which the young

women of Greek households could be sent honorably and safely to collect what was needed for family use. Naturally, these locations became the settings for tales of

nymphs and maidens.

Spring nymphs figure centrally in local genealogies. Regularly identified as the very earliest ancestors, these nymphs supposedly married into local royal families, providing a hereditary link to the natural environment and, for future generations, an implicit claim upon the land.

42

Myths emerged from local landscapes, helping to explain how things came to be as they are. Generations of

Athenians believed in a common ancestry all blessed by local divinities that inhabited an intimately familiar

topography. This common origin is the key to Athenian

identity and solidarity. It makes possible a communal spirit while also potentiating a chauvinism vis-à-vis other Greeks, to say nothing of lesser peoples. Such beliefs, whether real or fanciful, dominate collective imagination and shape a worldview of past, present, and future. To stand in the same cave or at the same spring as one’s great-great-grandmother did; to set the same offering of fruit, grain, meat, or honey on the same

altar in a

ritual performed by blood relatives centuries before; to perceive that fellow citizens share one’s genetic continuity with a very ancient past—the power of these experiences attests to the oft-claimed truth that nothing defines identity and belonging like the ways in which individuals and communities remember and forget.

43

And since human beings tend to comprehend identity best as a narrative, the stories that the Athenians told themselves and the setting of these tales are the key to understanding not only who they believed they were but also their most monumental collective efforts.

THE MODERN CITYSCAPE

of Athens has all but eclipsed the rich network of ancient

springs and

waterways, now buried beneath congested thoroughfares. Street names preserve their

memory and track their courses: Kifissou Avenue runs atop the Kephisos River some 3 kilometers (2 miles) to the west of the Acropolis, while Kallirrhöe Street, at the southeast, begins near its eponymous spring and carries on to the south following the route of the

Ilissos River that runs beneath it. The tributary of the Kephisos, the

Eridanos River, courses underground to the northwest of the Acropolis skirting the north flank of the Agora. A stretch of its wide riverbed, some 50 meters (164 feet) across, was rediscovered during the digging of the Constitution Square metro station in the late 1990s beneath Amalias Avenue at Othonos Street.

44

The Eridanos flows on toward Mitropoleos Square, where it manifests itself in the presence of a few old plane trees now growing among the tables of the street cafés.

To the east of the Acropolis, the Ilissos River, long converted into an underground rainwater conduit, flows along its original course beneath

Mesogeion, Michalakopoulou, and Vasileos Konstantinou Avenues. From here it runs past the ancient spring of Kallirrhöe and carries on beneath Kallirois Avenue through the suburb of Kallithea, from which it has been routed, in modern times, directly into the Bay of

Phaleron. But, in antiquity, the Ilissos circled around to the south of the Acropolis, coursing westward to join up with the Eridanos before emptying into the Kephisos and flowing on into Phaleron Bay.

The three rivers of Athens rise in the mountains to the north of the city: the Kephisos flows from

Mount Parnes, the Ilissos from

Mount Hymettos, and the Eridanos from

Mount Lykabettos (

this page

and

this page

). These waterways would have been the principal points of reference for the city, sustaining vibrant ecosystems, providing a focus for human activity, and serving as thoroughfares for transporting goods and people. While Plato’s

Phaidros

paints an idyllic image of the pastoral along the Ilissos’s grassy banks, we must acknowledge that the reality on the ground might have been quite different. An inscription, dating to the late fifth century

B.C.

, forbids that anyone tan hides or throw litter into the Ilissos, further stipulating that no animal hides should be left to rot in the river above the temple of

Herakles.

45

Similarly, the Eridanos was so filthy in antiquity that it was said no Athenian maiden could draw “pure liquid from it” and “even cattle backed off” from its waters.

46

The Kephisos is the largest of the three rivers. It gushes south for some 27 kilometers (16.8 miles) from the foothills of Parnes, a great mountain where wild boars and bears once roamed.

47

Coursing south across the

Thriasion Plain to the west of Athens, the river eventually flows into the Bay of Phaleron. Today, it can be seen channeled in conduits running alongside the

Athens-Lamia National Road and, for its southernmost 15 kilometers (9 miles), languishing in canals beneath the four-lane elevated highway known as

Kifissou Avenue, a place for dumping garbage and toxic waste. An environmental reclamation effort is under way.

48

For now, though, the Kephisos bears little resemblance to the noble river of antiquity, one so revered that it was worshipped at its own sanctuary.

The shrine was located close to the place where the Ilissos joined the Kephisos, about halfway between the port of

Piraeus and Phaleron. Around 400

B.C.

, a man named

Kephisodotos (“Given by the Kephisos”) dedicated a marble relief stele here.

49

It is likely that he was named by grateful parents whose

prayers for a child had been answered favorably

by the river. Greeks prayed to rivers to help them conceive children, and we can detect a certain trend toward

potamonymy (“naming after rivers”) in communities flanking famous streams.

50

Moisture being essential for conception and growth, it follows that rivers and their female offspring, the

nymphs, were closely associated with the begetting and nurturing of children.

51

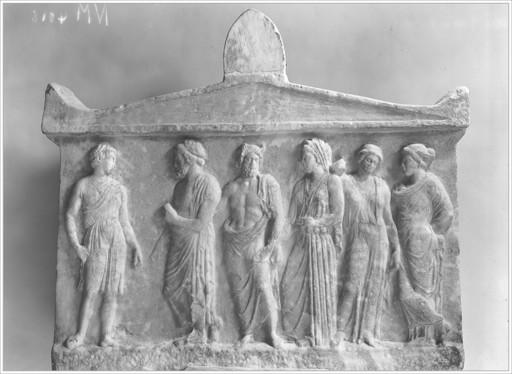

In the sculptured stele offered by

Kephisodotos (below), he perhaps stands as donor, second from left, between a female figure of uncertain identity (

Artemis?) and a personification of the Kephisos, at center; three spring nymphs follow behind. The sanctuary in which Kephisodotos set up this dedication had, in fact, been founded by a woman named

Xenokrateia just ten years earlier. It seems that she may have vowed to dedicate her young son to the river but, because of the

Spartan invasion of Attica at this time, she was unable to move beyond the city walls. Xenokrateia found an ingenious solution to this dilemma by establishing her own new shrine to the Kephisos in a protected area where the river flowed inside the city’s Long Walls. Here, Xenokrateia offered a marble relief to the Kephisos, and to the “altar-sharing gods,” as “a gift for the

didaskalias

” (“instruction” or “upbringing”) of her son,

Xeniades.

52

The stele shows Xenokrateia standing behind her little boy (following page), who reaches up to a male figure that must be the Kephisos River. At the far right of the scene we see Acheloös, whose cosmic, primordial identity makes him an ideal prototype for all Greek rivers.

53

Portrayed as a man-headed bull, here he does not specifically reference the great old river of Akarnania but, instead, represents the riparian nature of the shrine, just like that encountered by Sokrates and Phaidros on the banks of the Ilissos in the passage quoted at the opening of this chapter.

Marble relief stele dedicated by Kephisodotos, shown second from left, followed by the Kephisos River (with horns) and three nymphs. (illustration credit

ill.7

)

Marble relief stele dedicated by Xenokrateia, shown in foreground, at left, with young son who reaches up to the Kephisos River; the bull-bodied Acheloös at far right. (illustration credit

ill.8

)

The child-nurturing powers of the Kephisos are further attested by a marble statue group that

Pausanias spies as he’s passing along its banks in the second century

A.D.

54

The sculptures showed a woman named

Mnesimakhe and her little son depicted in the very act of cutting his hair as a votive offering. We know from many sources that first locks were cut from the hair of children and offered to rivers as “a token of the fact that everything comes from

water.”

55

Here, we see something of the very personal relationships that bound Athenians with the rivers that made life itself possible.

The relief sculpture dedicated by Kephisodotos shows the Kephisos River as a man with small horns. Euripides calls the Kephisos “bull-visaged” in his play the

Ion.

56

Even the loud rushing of the river’s currents is likened to the deep, lowing sound of a bull. We have also seen

the grand old river Acheloös appearing as a horned bull with a human face on the votive relief dedicated by

Xenokrateia. As the second-largest river in Greece, flowing in the west between

Akarnania and

Aitolia, the Acheloös was regularly depicted in vase painting as a bull- or human-headed bovine with a great beard, denoting its venerable age.

57

Three other Greek rivers are named Kephisos: one flowing from

Mount Parnassos near

Delphi, another from Mount Kithairon and through the

Nysian Plain near

Eleusis, and another at

Argos where,

Aelian tells us, the people portrayed their Kephisos with “a likeness to cattle.”

58

The Kephisos of Athens, bullish as the rest, played a prominent role in the great procession of initiates who marched

from Athens to Eleusis as early as the seventh century

B.C.

for induction into the Mysteries. In September of every year for a thousand years, worshippers walked west from Athens along the 14-kilometer (9-mile)

Sacred Way to the

sanctuary of Demeter and Kore. This was an occasion to which youths and scoundrels of Athens greatly looked forward. For on this day, they were allowed to stand by the Kephisos bridge and shout gross obscenities at their elders marching in silent procession, unable to speak back. We learn that to enjoy such sport, men and women, or perhaps men dressed as women, wore masks and veils to hide their faces as they harassed those crossing the bridge.

59

This misbehavior was ordained by the sacred rite and is typical of role-reversing cult practices in which people of lower rank are temporarily given license to mock their superiors. Such suspension of social hierarchies may have enabled participants in the Mysteries to approach Demeter and Kore with a fitting sense of humility.

60

In any case, bridges and bad language went together. The Greeks even had a word for it,

gephyrismos

, or “bridginess,” and in

Plutarch “bridge words” correspond to our “four-letter words” today.

61