The Parthenon Enigma (2 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

Walhalla memorial, Regensburg, Bavaria, 1830–1842, Leo von Klenze, architect. (illustration credit

ill.2

)

The tendency to see oneself in ancient artistic masterpieces is not, however, limited to the adherents of any particular political ideology.

Cecil Rhodes viewed the Parthenon as a manifestation not of democracy but of empire. “Through art, Pericles taught the lazy Athenians to believe in Empire,” he maintained.

13

Karl Marx, also attracted to Greek art, preferred to understand classical monuments as products of a society not at its peak but in its infancy. “The charm of [Greek] art,” Marx argued, “was inextricably bound up” with “the unripe social conditions under which it arose.”

14

The splendor of high classical art in general, and the Parthenon in particular, would hold irresistible attraction for the fascist regime of Hitler’s Germany, which readily appropriated it in the service of its ideological, cultural, and social agendas.

15

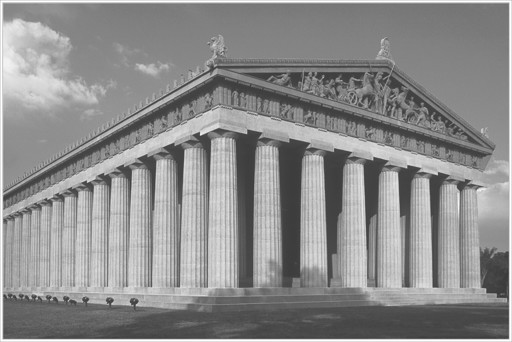

Nashville Parthenon, Centennial Park, Nashville, Tennessee, 1920–1931. (illustration credit

ill.3

)

Should we be surprised that

Sigmund Freud’s response to the Parthenon was one of guilt? He was tortured by the fact that he had been privileged to see a masterpiece that his own father, a wool merchant of modest means, could never have seen or appreciated. Indeed, Freud was riddled with guilt at the thought of having surpassed his father in this good fortune.

16

In 1998, the editor

Boris Johnson, now mayor of London, published in

The Daily Telegraph

an interview with a senior curator at the

British Museum. Johnson quoted the curator as saying that the

Elgin Marbles are “a pictorial representation of England as a free society and the liberator of other peoples.”

17

Thus, the Parthenon serves as both magnet and mirror. We are drawn to it, we see ourselves in it, and we appropriate it in our own terms. In the process, its original meaning, inevitably, is very much obscured.

Indeed, our understanding of the Parthenon is so bound up with the history of our responses to it that it is difficult, if not impossible, to separate the two. When the object of scrutiny has been thought so matchlessly beautiful and iconic, a screen for meanings projected upon it across two and a half millennia, it is all the more challenging to

recover the original sense of it. What is clear is that the Parthenon matters. Across cultures and centuries its enduring aura has elicited awe, adulation, and superlatives. Typical of the gushing is that of the Irish artist and traveler

Edward Dodwell, who spent the years 1801–1806 painting and writing in Greece. Of the Parthenon he declared, “It is the most unrivaled triumph of sculpture and architecture that the world ever saw.”

18

This same sentiment inflamed

Lord Elgin, less a man of words than of action. In fact, during the very years of Dodwell’s stay in Athens, Lord and Lady Elgin and a team of helpers were busy taking the temple apart, hoisting down many of its sculptures and shipping them off to London, where they remain to this day.

Even the removal of its sculptures, however, could not dull the building’s allure. In 1832, the French poet

Alphonse de Lamartine, last of the Romantics, declared the Parthenon to be “the most perfect poem ever written in stone on the surface of the earth.”

19

Not long thereafter, the neo-Gothic architect

Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc proclaimed the

cathedral at Amiens to be “the Parthenon of Gothic Architecture.”

20

Even the great arbiter of twentieth-century modernism Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, later known as Le Corbusier, upon first seeing the Parthenon proclaimed it “the repository of the sacred standard, the basis for all measurement in art.”

21

And so the Parthenon’s larger-than-life status has had a profound effect on the ways in which it has been scrutinized, what questions have been asked of it, and, more interesting, what questions have been left unasked. Too revered to be questioned too much, the Parthenon has suffered from the distortions that tend to befall icons. The fact that so few voices from antiquity survive to tell us what the Athenians saw in their most sacred temple has only enlarged the vacuum into which post-antique interpreters have eagerly rushed.

IT HAS NOT HELPED

the effort to recover original meaning that beginning in late antiquity, long after Athens had lost its independence, the Parthenon suffered a series of devastating blows. Around 195

B.C.

, a fire consumed the cella, the great room at the eastern end of the temple. At some point during the third or fourth century

A.D.

, under Roman rule, there was an even more ruinous fire. Some scholars have pointed to the attack by the Germanic Heruli tribe in

A.D.

267 as the cause of

this destruction, while others have attributed it to the

Visigoth marauders under

Alaric, who plundered Athens in 396.

22

Whatever the cause, the Parthenon’s roof collapsed, destroying the

cella. The room’s interior colonnade, its eastern doorway, the base of the cult statue, and the roof had to be entirely replaced.

23

The Parthenon’s days as a

temple of

Athena were now numbered. Between

A.D.

389 and

A.D.

391, the Roman emperor Theodosios I issued a series of decrees banning temples, statues, festivals, and all

ritual practice of traditional Greek polytheism. (It was Constantine who legalized

Christianity, but it was Theodosios who outlawed its competition, making it the state

religion.) By the end of the sixth century and possibly even earlier the Parthenon was transformed into a Christian church dedicated to the Virgin Mary. This conversion required a change in orientation, with a main entrance now smashed open at the western end of the structure and an apse added at the east (

this page

). The westernmost room became a narthex, while a three-aisled basilica stretched toward the east in what had been the temple’s cella. A baptistery was introduced at the building’s northwest corner.

24

By the late seventh century this church had become the city’s cathedral under the name of the

Theotokos Atheniotissa, the “God-Bearing Mother of Athens.” When, in 1204, Frankish forces of the

Fourth Crusade invaded, they converted the Greek Orthodox cathedral into a Roman Catholic one, renaming it

Notre-Dame d’Athènes. A bell tower was added at its southwest corner. With the fall of Athens to the

Ottoman Turks in 1458, the Parthenon was rebuilt once again, now as a mosque, complete with a mihrab, a pulpit, and a soaring minaret on the very spot where the bell tower had stood.

Having survived largely intact for more than two thousand years, the Parthenon suffered a catastrophic explosion on September 28, 1687. A week earlier, the Swedish

count Koenigsmark and his army of ten thousand soldiers had landed at

Eleusis, just fourteen kilometers to the northwest. There they joined the Venetian general

Francesco Morosini for the siege of Athens, but one front in the larger Morean War, also known as the

Sixth Ottoman-Venetian War, which lasted from 1684 to 1699. As the Venetian army advanced upon Athens, the Ottoman Turkish garrison defending the city barricaded itself on the Acropolis. The Turks had, by now, torn down the temple of Athena Nike at the western tip of the citadel and replaced it with a cannon platform. They stockpiled

live ammunition within the walls of the Parthenon itself. Over six days, the Venetians blasted an estimated seven hundred cannonballs at the Parthenon, shooting from the nearby Museion Hill. Finally,

Count Koenigsmark’s men scored a direct hit. The Parthenon erupted in a violent explosion that sent its interior walls, nearly a dozen columns on its north and south flanks, and many of its decorative sculptures flying out in all directions. Three hundred people died that day on the Acropolis. The battle would rage on for another twenty-four hours before the Turkish troops capitulated.

25

The sacred space of the Acropolis was thus forever changed, now acquiring a new iconic status as “ruin.”

26

By the early eighteenth century, a small square mosque was built within the rubble of what had been the Parthenon’s

cella. Made of brick and reused stones, the domed structure (with a three-bayed porch facing northwest; see

this page

) sat within the fallen framework of the Parthenon’s colonnade until it was damaged in the

Greek War of Independence and subsequently removed in 1843.

27

IN SOME SENSE OUR

bias toward seeing the Parthenon in political terms can be put down to a success of scholarship: the political sphere of Athens in the fifth century

B.C.

is the one we know best. The survival of a relative wealth of literature and inscriptions by, for, and about classical Athenians provides access to the world of Perikles, the general and politician who so shaped what is known today as the golden age of Greece, with which the flourishing of democracy is very much bound up. Yet there is much more to Athenian culture than democracy and more to its conception of democracy than what can be perceived by viewing it through a modern lens. For one thing, the Athenian notion of politics transcends our own.

Politeia

is difficult to translate in English; in fact, the word embraces all the conditions of

citizenship in its widest sense. Ancient

politeia

extended far beyond the parameters of modern politics, embracing religion,

ritual, ideology, and values.

Aristotle intimates that the primacy of the “

common good” played a definitive role in

politeia

, observing that “those constitutions that aim at the common good are in effect rightly framed in accordance with absolute justice.”

28

At the very core of Athenian

politeia

lies the culture’s fundamental understanding of itself and its origins, its cosmology and prehistory—a

nexus of ideas that defined the values of the community and gave rise to a complex array of

ritual observances of which the Parthenon was the focal point for nearly a thousand years. Until now, the Parthenon has received relatively little consideration in this light. And yet without such understanding it is impossible to say satisfactorily just what the Parthenon is beyond a supreme architectural achievement or a symbol of a political ideal as understood by essentially foreign cultures in the remote future. If we are to recover the primordial and original meaning of the Parthenon, we must endeavor to see it as those who built it did. We must see it through ancient eyes, an effort that involves the archaeology of consciousness as much as of place.

This aim of discovering the ancient reality of the Parthenon has been advanced by recent archaeological and restoration efforts on the Acropolis as well as by fresh anthropological approaches that are ever widening our understanding of the ancient past. Concrete archaeological discoveries made by the

Greek Ministry of Culture’s

Acropolis Restoration Service in its meticulous autopsy of the building have revealed new information on the materials, tools, techniques, and engineering employed in the Parthenon’s construction.

29

We now know many changes were introduced in the course of building the Parthenon, which may have included the pivotal addition of its unique and magisterial sculptured frieze. It has now been established that this frieze originally wrapped around the entire eastern porch of the temple. Two windows, on either side of the Parthenon’s east door, allowed extra light to flood in upon the statue of Athena. Traces of a small shrine with an

altar have been discovered in the temple’s northern peristyle, marking the place of a previously unknown sacred space that predates the Parthenon.

30

This opens the way for a new understanding of

pre-Parthenon

cult ritual and raises questions concerning the continuity of sacred space from deep antiquity to the age of Perikles.

The last decades have seen much more than the proliferation of new data on the design and evolution of the Parthenon as a building. They have also brought sweeping shifts in scholarship that allow us a view of the Parthenon in its more immaterial dimensions. New questions are being asked of the ancient evidence, with new research models and methods deployed to ask them, drawing on the social sciences and religious and cultural history. These have generated a fresh approach to monuments viewed within the fullness of a whole variety of ancient contexts.

31

The study of Greek

ritual and religion has burgeoned over the past thirty years.

32

The embeddedness of religion in virtually every aspect of ancient Greek life is now fully recognized. The study of ancient emotions and also cognition is under way, revealing the effects of language, behavior, and multisensory experience on feeling and thinking in the ancient world.

33

We are in a better position than ever before to get inside the heads of those who experienced the Acropolis in Greek antiquity.