The Parthenon Enigma (4 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

Plato,

Phaidros

230b–c

2

In this intimate portrait of Sokrates enjoying the simple pleasure of lying with his head deep in the summer grass, Plato evokes not only the humanity of the philosopher, who was his teacher, but also the idyllic natural environment that blessed the city of Athens.

As they’d approached the shade of the river’s edge, Phaidros’s thoughts had turned immediately to myth. “Tell me, Sokrates, isn’t it from somewhere near this stretch of the Ilissos that people say Boreas [the North Wind] carried

Oreithyia away?…Couldn’t this be the very spot?” he inquires. “No,” Sokrates replies, that place is “two or three hundred yards farther downstream, where one crosses to get to the district of Agra. I think there is even an

altar to Boreas there.” Looking up at the doll-like figurines placed here by worshippers, Sokrates surmises that this must be a spot sacred to the river god Acheloös and the nymphs. Before long, he feels the effects of the mythically charged location: “There’s something truly divine about this place, so don’t be surprised if I’m quite taken by the Nymphs’ madness as I go on with the speech. I am on the edge of speaking in dithyrambs.”

3

Sokrates might be forgiven for his spontaneous mouthing of those ecstatic

hymns to

Dionysos. For these passages from the

Phaidros

reveal how inseparable were myth, landscape,

memory, and the sacred within

Athenian consciousness—and also what collective power they exerted on the emotions.

4

With signs and symbols of local piety and

ritual abounding, Sokrates’s own short bout of

nympholepsy (in his day, an agitation induced by proximity to actual nymphs) makes palpable for us the power of place.

5

The presence of the gods is real to Sokrates and Phaidros, men of the highly educated elite of the city. While Sokrates may be loath to speculate on the myth of Boreas and Oreithyia (daughter of the mythical king

Erechtheus and his wife,

Praxithea), he is happy enough to accept common opinion on the setting for the story.

6

The

ancient landscape bristled with such localities charged with meaning, natural landmarks experienced with an intensified

awareness by generations of

Athenians, privileged and humble, educated and unschooled alike.

We begin our examination of the Parthenon with its broader natural surroundings, the landscape that so shaped Athenian consciousness of place and time, of reality itself (below). It is out of

Attica—the greater territory surrounding Athens—that the forces of nature and divinity, of human drama and history, issued. To commemorate their favorable resolution required nothing less than what the Parthenon would be: the largest, most exquisitely planned and constructed, lavishly decorated, and aesthetically compelling temple that the Athenians would ever build. It would also be a monument steeped in carved images retelling vibrant stories from the city’s mythical past. For in the Greek view, mythos (a “saying” or “story” without rational claim to truth) and history (the empirical search for truth about the past)

7

were often indistinguishable;

both were inscribed in epic and

genealogical narratives set in a landscape thought to have existed since the world was created out of chaos.

Places of memory within this landscape held special meaning for generations of inhabitants who passed age-old narratives down to their

children.

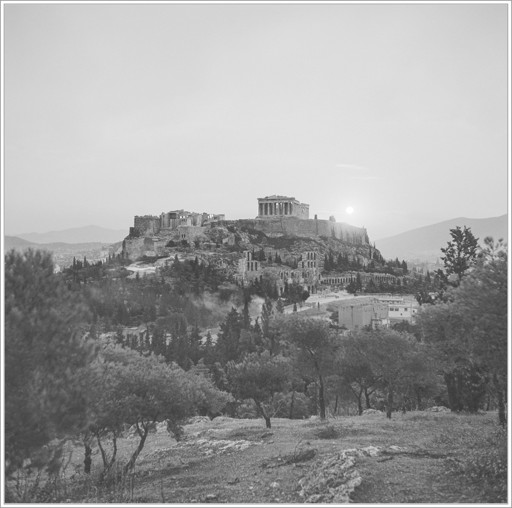

Acropolis at dawn from west. © Robert A. McCabe, 1954–1955. (illustration credit

ill.4

)

The Greeks comprehended their distant past according to certain fixed “boundary catastrophes” that punctuated and divided time into distinct eras.

8

Cosmic battles, global deluge, and epic wars are chief among the catastrophes that marked the succession of one period by another: in the early chapters of this book we shall consider the power of each sort of upheaval. (All show influence from the ancient Near East, some of it direct, but much via Syro-Palestinian and Phoenician sources.)

9

But of the three disruptive forces, none, of course, could have done more to shape the landscape or the culture’s awareness of it than the ebb and flow of water. The recurrence of floods and deluges became a definitive means for dividing time into eras, the division between the antediluvian and the diluvian being as important to the Greeks as to the Sumerians and Hebrews.

The recounting of ancient narratives that describe era-defining floods, clashes among the gods, and epic battles of Greeks against exotic “others” (Amazons, Centaurs, Trojans, and Thracians) was utterly essential to Athenian paideia (education) and piety. That these phenomena played out in an ancient landscape still visible to Athenians of the historical period bound them to a mythic past in a way scarcely imaginable to us; for them the remote past was not remote but immanent in everything. The meaning of the Parthenon—the sense of its design and decoration, no less than its location—cannot be understood without wading into the spring of associations from which it issues. To do so, we must start at ground level with the ecology and topography of the ancient city.

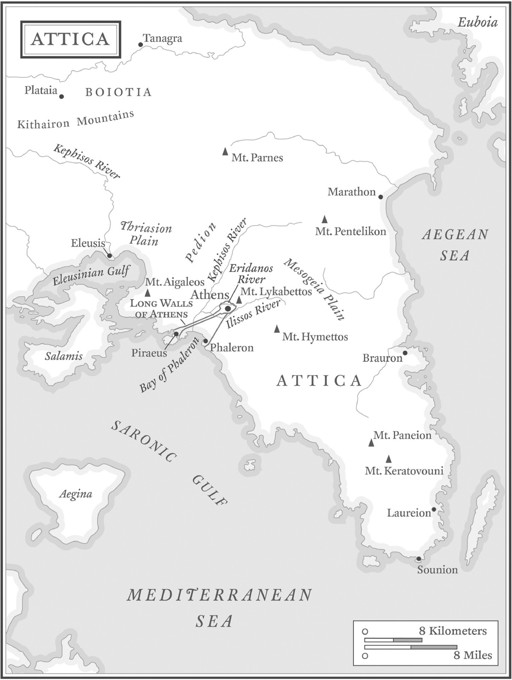

ATTICA COMPRISES

a triangular peninsula of some 2,400 square kilometers (927 square miles) that juts into the Aegean Sea at the very southeast corner of the Greek mainland (facing page).

It is bordered on the northwest by the

Kithairon Mountains, some 104 kilometers (65 miles) distant, a range that separates it from the neighboring territory of Boiotia. Mounts Parnes and Aigaleos rise to the north and west of Athens; Mounts

Pentelikon and Hymettos lie to its northeast and east. Mounts Keratovouni and Paneion sit to the southeast of the city, near

Laureion. In between these mountains stretch four valleys and three great plains: the

Mesogeia Plain to the east of

Mount Hymettos, the

Pedion (literally, “Plain”) to the northwest of Athens, and the

Thriasion Plain between Athens and

Eleusis. The Acropolis (

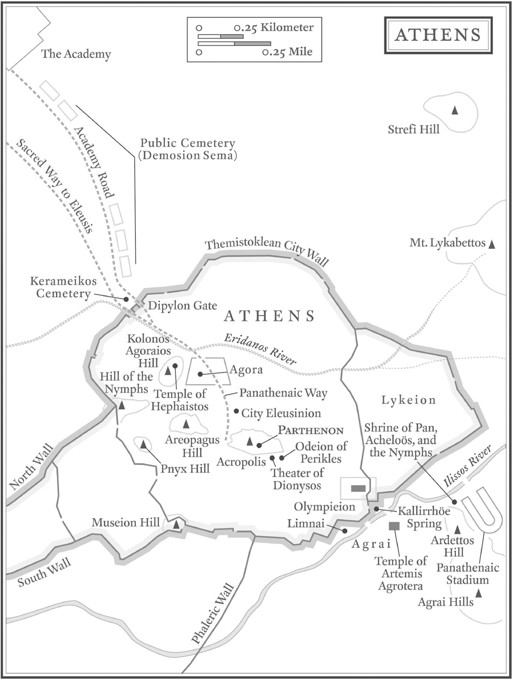

literally, “Peak or High Point of the City”) is one of a series of smaller hills that rise within Athens itself (facing page).

10

The Areios Pagos, or Areopagus (“Hill of Ares”), sits just beside it at the west, with the Kolonos Agoraios to the northwest skirting the ancient marketplace, or Agora. Farther to the west rise the

Pnyx and the

Hill of the Nymphs, while at the southwest sits the

Mouseion Hill.

Ardettos Hill rests to the southeast of the Acropolis beyond the city walls, and farther away at the northeast we find

Mount Lykabettos and

Strefi Hill. Even farther north rises the ancient Anchesmos (“Sharp-Peaked”) Hill, later called

Lykovounia (Wolf Mountains) and, today, Tourkovounia (a more recent reference to Ottoman times). At the south, Attica opens onto the

Saronic Gulf through a series of excellent harbors and bays (previous page). It has been estimated that by the 430s

B.C.

, Attica had a

population of between 300,000 and 400,000 people. About half of these are believed to have lived in Athens and the area immediately surrounding it.

Map of Attica. (illustration credit

ill.5

)

It is difficult to grasp today, given the density and overdevelopment of modern Athens, just how diverse the

ecosystems of ancient Attica were. Already in Plato’s time, there was a sense that the countryside had changed dramatically over the preceding millennia. In the

Kritias

, he tells us that the Attic landscape once had mountains with high arable hills, fertile plains deep with loamy soil, and thick forests all around.

11

Still, even in his day, the countryside was rich with olive and plane trees, oaks and cypresses, Aleppo pine, cedar, laurel, willow, poplar, elm, almond, walnut, and mastic as well as the evergreen bushes myrtle and oleander. Fruit-bearing trees kept Athenians happy with figs, pears, apples, plums, cherries, pomegranates, and more. Vines and vineyards provided grapes for eating, for drying as raisins, and for making wine. No doubt, vine-entwined arbors provided shade for outdoor living much as they do today. Giant fennel grew wild, along with broom, eglantine, ivy, buckthorn, hemlock,

akanthos, and celery.

12

Vegetable gardens provided garlic, onions, and prickly lettuce as well as broad beans, lentils, chickpeas, and other legumes. A host of herbs, including thyme, sage, oregano, and mint, enlivened the local cuisine.

The fertile fields of the Attic countryside (

chora

) fed thriving agricultural ventures that produced olives, cereals, and vines (

this page

). Barley and (to a lesser extent) wheat were grown as mainstays of the diet under a system of crop rotation that left half the land fallow in any given year.

13

Above all else, Athenians valued the self-sufficiency that these

farms, fields, plantations, and groves brought to their extended families.

14

Indeed, the greatest product of Athenian agriculture was the sense of autonomy and independence it brought the people, a citizenry based on landownership. Of course, during the

Peloponnesian War, Athens’s survival depended on foreign food imports, especially grain, to supplement local production.

15

Nonetheless, Athens prided itself on being an

autarkestate polis

(a “self-sufficient city”), an ideal held up by Aristotle as a shining virtue of the state.

16

Map of Athens. (illustration credit

ill.6

)

In so many ways the stability and security brought by these private farms created the conditions for the unprecedented rise of democracy—and eventually undemocratic excesses as well. The population boom of the eighth century and subsequent scarcity of land, increasingly concentrated in the hands of a superrich aristocracy, would threaten this agrarian stability until, around 594

B.C.

, the statesman (and poet)

Solon was authorized to introduce reforms.

17

His measures helped the peasantry by banning

slavery for debt, limiting the amount of land one family could hold, and greatly increasing the number of free, landholding citizens. Still, one’s level of civic participation and representation in government remained commensurate with one’s landholdings. In the new scheme of social census classes introduced by Solon’s reforms, citizens of the uppermost rank, the

pentakosiomedimnoi

(named for the fact that they owned enough land to produce five hundred measures of grain a year), were eligible for the highest offices of

treasurer and eponymous

archon (chief magistrate). The next class, the

hippeis

(named for those who could afford to maintain a horse and thus participate in the cavalry), held property that produced three hundred measures of grain per year. Next came the

zeugitai

, or teamsters (named for those who maintained a pair of oxen that could be yoked for plowing), whose land produced two hundred measures a year. The lowest class belonged to the

thetes

, or common laborers, who owned no land whatsoever and could participate only in the assembly (of all citizens) and, importantly, as

jurors on law courts. Ownership of land and the cultivation of grain thus rested at the very heart

of Athenian civic engagement. Indeed property came to define Athenian belonging almost as much as

genealogy, both being hereditary privileges. By the fourth century, the “

Ephebic Oath,” in which young men reaching the age of eighteen pledged to defend the state, spoke as much of agricultural as religious patrimony: