The Passport in America: The History of a Document (7 page)

Read The Passport in America: The History of a Document Online

Authors: Craig Robertson

Tags: #Law, #Emigration & Immigration, #Legal History

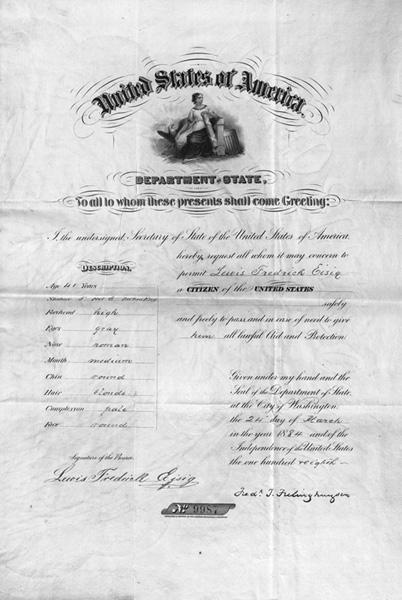

Figure 1.7. Passport issued in 1884 (National Archives, College Park, MD).

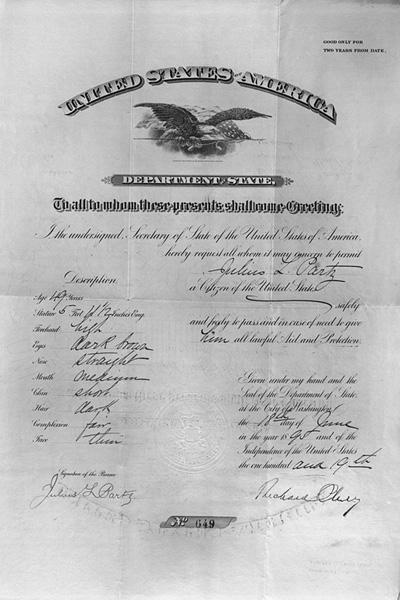

Figure 1.8. Passport issued in 1895 (National Archives, College Park, MD).

of 1914 a second seal was attached to the passport to secure the photograph to the document. When the passport design was adapted in 1918 to accommodate photographs more easily, the seal was impressed on a red paper wafer glued to the passport, partly on the photograph and partly on the document.

These changes to the way in which the State Department represented its authority imply an acknowledgement of the importance of such representations to the utility of the passport. However, the link between a document and an external authority such as the federal government was not made in an uncontested fashion, nor was the assumption that a piece of paper could represent an individual’s identity and the authority authenticating that identity. The uncertainties and challenges associated with the development of the passport were part of a broader use of printed documents and acceptance of the impersonal nature of their authority in situations where authority traditionally tended to derive exclusively from personal presence or personally established reputation. In NineteenthCentury U.S. culture the debate over the authenticity and legitimacy of printed documents and their ability to represent something or someone was more apparent in the development of paper money.

The United States was arguably at the forefront of the widespread adoption of paper money in the Western world, as opposed to the short-term circulation of notes and the “scriptural money” created through bookkeeping that had characterized much of the “money” in Europe prior to this period.

23

This early form of paper money descended from established forms of financial and contractual documentation that included loans, promissory notes, conveyances, and receipts. The successful transformation of these into a document that circulated widely as the representation of value required a negotiation of authority. Paper money had to be accepted as representing something it was not. Coins were understood to be both something of value in and of themselves and a symbol that represented that value. In contrast, paper money was a piece of paper.

In the first half of the nineteenth century currency took the form of banknotes, pieces of paper that represented a certain amount of money in specie. The notes contained the signature of the bank’s owner, which indicated that a particular person (the bank owner) possessed the amount of money in specie represented in the note. However, these notes tended to circulate beyond a local context where someone could be expected to personally know, or even know of, the bank owner. Therefore, banknotes produced the still novel

situation of documents in everyday interactions being trusted to represent an authority that existed beyond personal knowledge, while employing techniques traditionally associated with personal knowledge and reputation—a personal name and signature. The acceptance of banknotes, their circulation amongst strangers, therefore, demanded the acknowledgment of a new model of communication. Along with other forms of written authority that traveled beyond personal knowledge of the author they constituted a particular form of impersonal communication that required confidence in the medium of printed paper.

24

In a very practical sense, this impersonal mode of interaction necessitated that people learn to work with documents, to understand and accept the authority of a document to represent “reality.” For banknotes this involved the acquisition of knowledge to determine if a banknote was authentic—that it was worth what it represented. With over five thousand different state bank notes circulating during the course of the nineteenth century, this was a useful skill to acquire.

25

It was made all the more crucial given the claim by one newspaper that in 1862 counterfeits existed of notes issued by all but 253 of the 1,389 state banks.

26

Aside from what people could find out from the trial and error of personal use, numerous newspaper articles and political tracts were written to help in the quick recognition of telltale signs of a counterfeit note. Specialist publications emerged known as “counterfeit detectors,” some with weekly circulations as high as 100,000. That printed publications existed to address suspicion about printed documents underscores the uncertainty and negotiation over the authority of printed words that characterized early life in an increasingly urban and market-driven United States.

27

The need to establish the authenticity and authority of paper money did not cease when the federal government for the first time began to issue paper money as a way to finance northern mobilization in the Civil War. The federal government, like a bank owner, was in some ways a stranger in the lives of its citizens, even if only to the extent to which hostility to centralized power continued to exist. The government employed a variety of strategies to impose order over the historically chaotic circulation of paper money. It taxed thousands of state-issued paper currencies out of existence and suppressed the private issue of tokens, paper notes, and coins by stores, businesses, churches, and other organizations.

28

Funds were also provided for a secret service to police currency, but with a limited budget and no clear guidelines for how to restrict the activities of counterfeiters it had limited success.

29

However, in 1881 the Chief of the Secret Service did order the destruction of 160 boxes of toy money, and a decade later an agent seized a painting of a U.S. note he found hanging in a saloon.

30

The novelty of policing the authenticity and authority of documents is also apparent in the frequent changes in the appearance of national currency. The standardization of U.S. currency was a gradual process—only in 1929 did it take on its now familiar size and appearance, sixty-eight years after the federal government began issuing it. These changes had increased the variety of notes in circulation, making it harder to recognize a counterfeit bill. In part this is because the aesthetic features of U.S. currency were more than an anticounterfeiting device. They were intended to convey an arguably more contested form of authority than paper money—that of the political authority of the federal government. On U.S. currency deliberate use was made of aesthetic features such as portraits, allegorical figures, historical scenes, and nationally recognized architecture. In this way national currency allowed the federal government to link its political authority to the more accepted cultural identity of American nationalism.

31

In the first four decades of use, more than fifteen different historical scenes appeared on currency, along with at least thirty different allegorical figures and over forty individuals. A contributing factor to this was the variety of forms federal currency took, from interest-bearing notes to silver certificates and national bank notes; this further undermined the ease with which currency could be easily recognized as authentically issued by the federal government.

32

These different forms, along with the creation of postal money orders (1864), travelers checks (1891), credit cards (1914), and the first electronic funds transfer (1918), indicate the increased need to trust “abstract” representations of authority and value—the necessity and capacity of money within a rapidly developing national market.

The passport followed a similar gradual path to becoming a standardized document. It appeared in its recognizable contemporary form as a booklet in 1926, three years before U.S. currency took on its now familiar form. The increasingly standardized appearance of the passport, as with currency, had the negative effect of increasing the possibility of fraud. This initially became a subject of concern during World War I but it became more widespread in the 1920s.

33

In this decade, with the introduction of immigration restriction, U.S. citizenship became an increasingly desired identity for immigrants denied entry to the United States through quota restrictions; in the first year of the 1924 quota system a special agent for the Division of Passport Control reported the discovery of fifty cases of passport fraud a month.

34

Newspapers frequently

carried stories of the breakup of so-called passport “factories” or “mills,” large-scale enterprises that produced fraudulent U.S. passports or visas. The individuals behind these often made use of counterfeit consular stamps and, less frequently, U.S. seals. Another tactic was to alter a legitimate passport either purchased or obtained through theft, and in the case of purported Bolsheviks from passports issued to American citizens sympathetic to the cause.

35

The State Department sought to counter false passports in two main ways. First, in 1924 it introduced shipside examinations of U.S. passports by its officials at some European ports, though not in France, where the government viewed U.S. officials determining whether an individual could leave its territory as a challenge to French sovereignty.

36

Second, the department tried to make the document more secure. By the 1930s the State Department regularly prepared detailed internal reports on techniques used to illegally produce or alter its passports. Using this knowledge, officials sought to make the passport resistant to tampering by improving binding techniques and the weave of cloth, and introducing a special type of paper on “which the slightest change by any method known to modern science can be readily detected.”

37

The most common methods for revealing the majority of fake or altered passports involved exposing unsuccessful attempts to replicate the watermark and inaccurate representations of the seal apparent in the letter size and spacing, and the appearance of the tail feathers (number and width), arrows (shafts, number, shape), and olive branch (number of olives, curve of the stem).

38

However, on occasions the State Department’s own officials undercut attempts to secure the passport. The actions of these officials indicate a failure to understand that the authority of the passport depended on the standardized production of the document more than the personal authority of the individual official issuing it. Passports issued abroad were often loosely constructed, thus producing a potentially fragile identification document. In the late 1920s the State Department still had to send reprimands to consuls for issuing passports with unclear seals or for attaching passport photographs with metal clips.

39

The consul in Panama was also asked to stop using a typewriter to fill in passports. Such a request makes clear the ongoing negotiation over standardization in terms of conflicting understandings of trust in its more traditional “personal” and newer “impersonal” form. The department discouraged the use of typewriters as an attempt at standardization, apparently favoring the imprint of the official as form of authenticity; a passport written in long hand was considered harder to alter.

40