The Perfect Heresy (5 page)

Read The Perfect Heresy Online

Authors: Stephen O'Shea

For the Perfect in St. Félix that day, there was no ecclesiastical hierarchy, no church as such, not even a building or chapel. The northern French Cathars would have shrugged at the laying of the cornerstone of Paris’s Notre Dame Cathedral four years earlier. To the dualists, the continuity of the consolamentum from the time of the apostles was the invisible edifice of the eternal, literally handed down from one generation to the next as a kind of supernatural game of tag. The sacrament was the lone manifestation of the divine in this world. The Cathars believed that Jesus of Nazareth, an apparition rather than a gross material being, had come to Earth as a messenger carrying the dualist truth and as the initiator of the chain of the consolamentum. The Nazarene’s death, if indeed he did die, was almost incidental; certainly it was not the unique redemptive instant of history as proclaimed by the Church.

The Perfect maintained that the cross was not something to be revered; it was simply an instrument of torture, perversely

glorified by the Roman faith. They also looked on aghast at the cult of saintly relics. Those bits of bone and cloth for which churches were built and pilgrimages undertaken belonged to the realm of matter, the stuff created by the evil demiurge who fashioned this world and the fleshy envelope of the human. He had created the cosmos, tempted the angels out of heaven, then trapped them in the perishable packages of the human body. What counted, in the greater scheme of things, was only one’s spirit, that which remained of one’s nature as a fallen angel, that which remained connected to the good. To think otherwise was to be deluded. The sacraments dispensed by the Church were nothing more than codswallop.

The pious outlaws of 1167 referred to the majority faith as “the harlot of the Apocalypse” and “the church of wolves.” Not for them Rome’s claims to temporal and spiritual preeminence. It had been ninety years since Hildebrand, the Tuscan radical elected as Pope Gregory VII, pronounced papal supremacy over all other powers. Kings, bishops, cardinals, and princes had been bickering ever since. Three years after the meeting at St. Félix, the thuggish confidants of Henry II of England broke into Canterbury Cathedral and murdered Thomas Becket, the archbishop who defied the royal demand to bring felonious priests to trial in secular courts. The assassination would be medieval Europe’s most notorious, but for the Cathars the act, aside from its abhorrent savagery, was totally without further meaning, having occurred in a void. There could be no legitimate kingdom, or church, of this Earth; thus the array of legal arguments presented by both Church and Crown amounted to utter casuistry.

The credentes were told to ignore other yarns spun in Rome. Catharism held that man and woman were one. A human being had been reincarnated many times over—as peasant, princess

, boy, girl—but again what counted was one’s divine, immaterial, sexless self. If the sexes insisted on coming together and thereby prolonging their stay in the world of matter, they could do so freely, outside of marriage, yet another baseless sacrament invented by a priestly will to power. The so-called Petrine commission, by which the pope still claims authority through direct descent from the apostle Peter, could also be ignored. The most fateful pun in Western history—“You are Peter, on this rock [

petra

] I will build my church” (Matthew 16:18)—failed to edify the Perfect. For them, the pope teetered atop a rickety fiction, his pronouncements a perpetual source of pointless mischief. The mania for crusades, begun in 1095, was a recent example. The journey to Jerusalem, with swords shamefully raised against other hapless prisoners of matter, had to be renounced for the journey within. All violence was loathsome.

There can be no doubt that these men and women of St. Félix were well and truly heretical, by every definition except their own. Nicetas would “reconsole” some of them who had journeyed there from Champagne, Ile de France, and Lombardy, so that they could be absolutely sure of their otherworldly credentials. To them, he was not a pope, or even a bishop in the traditional sense, but just a distinguished elder who had received the consolamentum properly and who should thus be treated with respect. Individual Cathars had their differences—some were more radically dualist than others—just as Catharism did not completely dovetail with Nicetas’s Bogomil creed. But that hardly mattered. The news of St. Félix’s extraordinary days of May proved something else, something far more disturbing to the exponents of orthodox Christianity. The heretics were now united in a novel, ominous way.

Prior to the meeting in 1167, heresy had seemed a sporadic affair, launched by charismatic loners taking advantage of a continent-wide upsurge in religious longing. Throughout the twelfth century, there were calls for a clergy more responsive to the spiritual needs of the growing towns. Religion was becoming personal again, and ephemeral messiahs and cranky reformers sprouted like weeds in an untended garden.

In Flanders in the 1110s, a certain Tanchelm of Antwerp rode roughshod over wealthy prelates, attracting an army of followers who, it is said, revered him so much that they drank his bathwater. Peasant Brittany fell under the sway of an illiterate visionary named Eudo. His disciples sacked monasteries and churches before he was declared a lunatic and thrown in prison. Nearby, in Le Mans, France, a wayward Benedictine monk called Henry of Lausanne profited from the bishop’s absence to turn the whole town into an anticlerical carnival. When the bishop returned and at last managed to reenter his city, the voluble Henry took to the road and headed south, accompanied by a retinue of smitten women. One commentator noted, in the lively metaphorical idiom of the day, that Henry “has returned to the world and the filth of the flesh, like a dog to its vomit.”

Tanchelm, Eudo, and Henry could at first be shrugged off by the Church as merely misguided in their enthusiasms. After all, orthodoxy had its own eccentric firebrands in this heyday of spiritual exaltation. The unkempt Robert of Arbrissel, a monk the equal of Henry for his preaching prowess, padded around in a skimpy loincloth wowing and winning female followers before

finally being prevailed upon to found an abbey for women and men at Fontevrault, in the Loire Valley. Another, Bernard of Tiron, was so given to producing and inducing fits of weeping that his shoulders were said to be perpetually soaking.

These men gradually gave way to less conciliatory preachers. Peter of Bruis unleashed an orgy of church pillaging and crucifix burning reminiscent of the iconoclasts of Byzantium. Like the Cathars, he was dismissive of Church wealth and the imagery of the cross. Unlike the Cathars, Peter was careless. At a bonfire of statuary near the mouth of the Rhône on Good Friday of 1139, he turned his back one time too many, and some enraged townspeople tossed him into the flames. More alarming yet was Arnold of Brescia, a former student of the great Peter Abelard. A rabble-rouser determined to save the Church from itself, Arnold proclaimed Rome a republic in 1146 and chased the terrified pope from the city. It would take eight long years before Nicholas Breakspear, the sole Englishman to be the pontiff, could move back to his residence at the Lateran Palace, thanks to the self-interested help of Emperor Barbarossa. Arnold was duly arrested, strangled, and burned, and his ashes were thrown into the Tiber, so that none of his large Roman following could start a cult with his corpse.

Yet even these extreme instances of Church-baiting could be ascribed, charitably, to an excess of reformist zeal. Such was patently not the case with the Cathars. They stood aloof from orthodoxy, and, as soon became obvious, they did not stand alone. Whereas there were few with enough physical stamina to live as Perfect, there were credentes by the thousands.

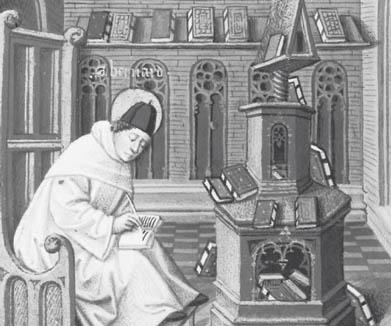

Bernard of Clairvaux

(Musée Condé, Chantilly/Giraudon)

In 1145, the influential Bernard of Clairvaux traveled to Languedoc to put the fear of God back into the followers of Henry of Lausanne. Mystical, anorexic, brilliant, eloquent, and polemical (he penned the sick dog trope cited earlier), Bernard was the greatest churchman of the century, a monk who was feared, admired, and obeyed more than any mere pope of the time. He proceeded in quiet triumph, feted and flattered everywhere as he wrested a few people away from Henry’s histrionics of protest. But Bernard was no fool; he sensed that there were other, more serious subversions afoot. At Verfeil, a market center northeast of Toulouse, the unthinkable occurred. Mounted knights pounded on the doors of the church and clashed their swords together, rendering Bernard’s sermon inaudible and turning his golden tongue to dust. The great man was laughed out of town.

Once safely back home in his monastic cell in Champagne, Bernard recovered his voice and sounded the alarm. A prodigious

letter writer, the great man informed his correspondents that what had previously only been suspected was now confirmed: Down-to-earth reform was being supplanted by the metaphysical rebellion of heresy. Like thunderstorms on a hot and unsettled summer’s day, dualists were sighted everywhere in western Europe. England, Flanders, France, Languedoc, Italy—no place seemed safe for the traditional Christian faith. In Cologne, Germany, in both 1143 and 1163, fires were lit under the feet of dualist believers, and a German monk who witnessed their torment labeled the unfortunates

Cathars

.

Understandably, the dualists were given to discretion. In 1165, several were brought before an audience in Lombers, a town ten miles to the south of Albi. In attendance were six bishops, eight abbots, the viscount of the region, and Constance, a sister of the king of France. Everyone in Lombers on that day knew that there was dry wood in the vicinity.

The Perfect, led by a certain Olivier, were cagey enough to cite the New Testament at soporific length. Wisely, they did not state that they entirely rejected the Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament, in keeping with their belief that the somewhat headstrong god described therein was none other than the Evil One, the creator of matter. In this, they rejoined the gnostics of antiquity. As for Jesus of Nazareth, they avoided saying that he was a mere apparition, a hallucination who could not possibly have been a being of flesh and blood. That—a heretical opinion known as Docetism—would have constituted a whopping contradiction of the orthodox doctrine of the Incarnation and given them away immediately.

Eventually, the Cathars at Lombers were flushed out on the question of oath taking. Citing Christian Scriptures, they said it was forbidden to swear any oath whatsoever, which was a red

flag in a society where sworn fealty formed the Church-mediated bond of all feudal relations. This aversion to oaths was a hallmark of Cathar belief, a logical extension of the clear-cut divide they saw between the world of humanity and the ether of the Good. When the role of the Church in the world was evoked, the veil dropped entirely, and Olivier and his fellow Cathars attacked the bishops and abbots at Lombers as “mercenaries,” “ravening wolves,” “hypocrites,” and “seducers.” Although offensive in the extreme to the churchmen, leveling such charges may have secretly pleased the assembled laity, who harbored no great love for the tax-gathering clergy. In the end, despite the universal sentiment that Olivier and his friends were heretics, everyone was allowed to go home unharmed. The lord of Lombers no doubt sensed that it would be impolitic to put local heroes to death.