The Pope and Mussolini (45 page)

Read The Pope and Mussolini Online

Authors: David I. Kertzer

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Europe, #Western, #Italy

Pius XI was surprised, appalled, and embarrassed by Mussolini’s meek acceptance of the Nazi takeover of Austria. “I am saddened as Pope,” he said, “but I am even more saddened as an Italian.” As for Vienna’s archbishop, the pope was furious at him. “He signed everything they put in front of him, everything they wanted.… And then he added, without any prompting, ‘Heil Hitler!’ ” The archbishops of Salzburg and of Graz had quickly followed Innitzer’s lead. The pontiff offered some choice words about the character defects of the Austrian people, which, he lamented, were unfortunately shared by the clergy there as well.

8

On the evening of April 1, a Vatican radio broadcast skewered the Austrian bishops for supporting the Nazi conquest. The following day the Vatican daily added to the criticism, noting that the bishops had prepared their statement without the Vatican’s approval. Pacelli, meeting

with the Italian ambassador, called Cardinal Innitzer’s behavior an embarrassment for the Church. The normally unflappable if high-strung Pacelli was visibly angry. Unfortunately, he said, in his job he sometimes had to deal with “people lacking character.”

9

But later, when Pacelli spoke with Germany’s ambassador, he was much more circumspect. Bergen complained about Vatican radio’s “inopportune utterances.” Pacelli tried to persuade him that the radio story was “neither official, nor semiofficial, nor inspired by the Vatican, and that the Pope also had nothing to do with it.” Pacelli here was stretching the cherished principle of deniability to its extreme limits, and the German ambassador had good reason to realize he was lying. The radio station was a project of the pope, who had enlisted the Nobel Prize–winning Guglielmo Marconi to help design it. With Marconi at his side, the pope had inaugurated it in 1931, his half-hour address—in Latin—reaching both sides of the Atlantic.

10

In Pacelli, the German ambassador thought, he had an ally. “The Cardinal added in confidence,” Bergen reported back to Berlin, “that after this unpleasant surprise he would try to institute some control over the Vatican station. The Cardinal repeatedly protested his fervent wish for peace with Germany.”

11

The pope summoned Innitzer to the Vatican. Vienna’s archbishop said he would arrive on the afternoon of April 5 but would need to leave the next morning as he had an appointment with Hitler that he did not want to miss.

12

Indignant, the pope sent word that he was not in the habit of having a cardinal dictate his schedule. Innitzer would return to Austria only when he chose to let him.

13

At their meeting, Pius told Innitzer that his behavior was disgraceful and instructed him to sign a retraction of his statement praising the new regime. “The solemn declaration of the Austrian bishops of March 18,” the statement began, “was clearly not intended to express approval of that which was not and is not in keeping with God’s law, with the freedom and rights of the Catholic Church.” It stressed that Austria’s concordat with the Vatican had to be respected, and that Austria’s children should be free to receive a Catholic education. The text, the German

ambassador reported, was “wrested from Cardinal Innitzer with pressure that can only be termed extortion.” Innitzer, wrote Bergen, “resisted to the utmost, but was able to effect only a few concessions.” The next day the archbishop’s statement was published in the pages of

L’Osservatore romano.

14

Pius was also upset with Mussolini, who had promised to protect Austria’s independence but then did nothing to stop the Nazi takeover. “The Duce,” remarked the pope to his old friend Eugène Tisserant, “lost his head some time ago.”

“Most Holy Father,” responded the French cardinal, “he lost it, I believe, during his trip to Berlin.”

“He lost it a long time before that,” replied the pontiff.

15

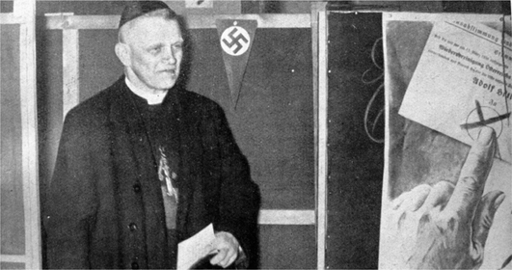

Cardinal Theodor Innitzer, archbishop of Vienna, casts his ballot in the Nazi plebiscite, April 10, 1938

The French increasingly viewed Mussolini and Hitler as kindred spirits, part of the same totalitarian threat to world peace. As French anger mounted at the pope’s support for the Italian dictator, Pius XI became the object of withering criticism. “On one side,” wrote Cardinal Baudrillart in his diary, “in the extremist newspapers, they accuse him of not fulfilling his moral mission and capitulating. On the other, some have mused that he should be offered a temporal state elsewhere (not Avignon) so that he is no longer at the mercy of (or an accomplice

of) Italy.” He concluded, “How embarrassed Cardinal Pacelli must be! What an end for Pius XI’s reign!”

16

IN THE WAKE OF

the Nazi takeover of Austria, Mussolini was feeling ill used. Humiliated by the invasion that he had long vowed to prevent, he summoned Tacchi Venturi and told him it was time to put an end to Hitler’s dreams of world domination. Half measures would be of no use, he warned, and hopes that Nazism would somehow simply peaceably fade away were naïve. Something dramatic was required, and it would have to come soon.

Who was in a position to take such action? The one man who could stop Hitler, the Duce told the flabbergasted Jesuit, was the pope. By excommunicating Hitler, he could isolate the Führer and cripple the Nazis.

17

What he proposed was so explosive that Tacchi Venturi would not put it in writing. He requested an urgent meeting with the pope, where he told Pius what Mussolini had said.

18

Knowing how temperamental Mussolini could be, and in any case not inclined to take such draconian action, the pope never seriously considered following the suggestion.

Curiously, Hitler’s excommunication may once have been officially considered at the Vatican, although there is no evidence that the pope knew anything about it. It was in January 1932, a year before Hitler came to power. The ground for excommunication was neither Hitler’s pagan ideology nor his campaign of race hatred but the fact that he had acted as a witness in a wedding of which the Church disapproved. That month a high German Church official told Italy’s ambassador to Germany that Hitler was in serious trouble with the Vatican. Joseph Goebbels, his acolyte, had gotten married, with Hitler serving as a witness. Goebbels, like Hitler, was Catholic, but the woman he married was not only a divorcée but a Protestant, and the ceremony had been performed by a Protestant pastor. For such a sin, excommunication, reported the high German prelate, was being discussed. If excommunication was in fact considered, the Vatican finally decided against it.

19

––

MUSSOLINI SOON CALMED DOWN

, telling himself that the German takeover of Austria had been inevitable. On reflection, Hitler’s display of strength only furthered his resolve to remain the Nazi’s ally. Now, far from wanting Pius to strike against Hitler, he again worried that the pope would turn Italians against the German alliance. With the Führer scheduled to visit Rome in the near future, he feared a fiasco.

As news of the Führer’s upcoming visit to Rome appeared more frequently in the press, much attention was devoted to the question of whether Hitler would visit the pope.

20

Although he despised Hitler, Pius would not, in principle, refuse to meet him. Hitler was the leader of a country with a huge Catholic population, a government with which the Vatican had full diplomatic relations. But the pope knew that many outside Italy would be unhappy at the sight of Hitler in the Vatican. It would certainly anger the French, and a report from the United States warned him that Americans would be outraged as well.

21

The Duce initially hoped that a historic visit between Hitler and

Mussolini dedicates the new Luce building with Father Pietro Tacchi Venturi and Achille Starace, November 10, 1937

Pius XI would be one of the highlights of the Führer’s triumphal tour of the Eternal City.

22

If Hitler came to Rome and shunned the Vatican, he worried, millions of Italians would be offended. No head of a state having relations with the Holy See, who had come to Rome in recent years, had failed to see the pope.

23

Although Pius was unhappy about the upcoming visit, Mussolini could still count on him to help with some of the arrangements. He worried about the sympathies of the foreigners who lived in Rome’s religious institutions that, under terms of the Lateran Accords, enjoyed the status of extraterritoriality. On March 26 Ciano contacted Cardinal Pacelli to ask for the pope’s assistance. In order to identify all foreigners suspected of anti-Nazi sympathies and place them under surveillance for the visit, papal police cooperation was crucial. A week later came the reply: “The secretariat of state is honored to communicate with all solicitude to the [Italian] Embassy that His Holiness has deigned to concede the desired authorization.” The Italian police were to contact their Vatican counterparts to arrange for the surveillance.

24

Although the pope wanted to maintain his close ties with Mussolini, he was upset at the monumental scale of festivities planned for the Führer’s arrival. A low-key visit would be understandable, he told the Italian ambassador. But how could the government prepare “the apotheosis of Signor Hitler, the greatest enemy that Christ and the Church have had in modern times?” He had prayed to God to take his soul back to Him before he had to suffer such a painful sight. As the pope contemplated the prospect, while talking with Pignatti, he choked up. The disgrace to the nation he loved was almost too much to bear.

25

Three days before the Führer’s arrival, the pope left the Vatican for his summer palace in Castel Gandolfo. He ordered the Vatican museums closed for the duration of Hitler’s visit and instructed the bishops in the cities along Hitler’s route not to attend receptions given in his honor. In the face of papal protests, the government abandoned its plans to set up giant spotlights to illuminate St. Peter’s.

26

L’Osservatore romano

published news of the pope’s departure, but denied it had anything to do with the Führer’s arrival.

27

For the pope, the drive to Castel Gandolfo was a bittersweet affair. It was a trying time for him, physically and spiritually, and he sensed this would be his last summer at his retreat in the Alban Hills. Some hint of these thoughts might be read into the unusual reception he hosted on his arrival. After blessing the crowd that gathered in the piazza to welcome him, he invited his staff to a little celebration. In the hall of the frescoes, as the monsignors joined him in conversation, he ordered vermouth brought in and served to all.

28

ON THE EVENING OF MAY

3, Hitler arrived at Rome’s train station, accompanied by Ribbentrop, Goebbels, Hess, Himmler, other Nazi leaders and diplomats, a gaggle of German journalists in uniform, and hidden from public view, his lover, Eva Braun.

29

Because he was head of the German state, protocol dictated that Hitler be met by the king and not by Mussolini. As the Führer stepped off his train, the Duce stood to the side fuming, forced to occupy a supporting role at a moment that he had been eagerly imagining for months. Hitler was surprised to be greeted not by the man he had hailed as a Roman emperor but by the little king with the big white mustache.