The Pope and Mussolini (41 page)

Read The Pope and Mussolini Online

Authors: David I. Kertzer

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Europe, #Western, #Italy

Much attention focused on the radio priest Charles Coughlin, whose increasingly vicious attacks on Franklin Roosevelt, in the midst of his 1936 reelection campaign, had divided America’s Catholic community and proven an embarrassment for the Vatican. The reason for Pacelli’s surprising visit,

The New York Times

speculated, was the pope’s desire to assure President Roosevelt that he had had nothing to do with Coughlin’s assault. Other papers predicted that Pacelli would shut down the fiery radio priest’s operation. Back in Rome, Italy’s ambassador to the Holy See had another explanation for the trip: Pacelli was campaigning to succeed Pius XI and was courting the favor of America’s four cardinals.

30

Boston’s Bishop Spellman took charge of the visit. The two men would fly from one end of the United States to the other, logging over eight thousand miles, making countless stops. Pacelli collected honorary degrees at several Catholic colleges, met with almost all of America’s bishops, and spoke to large gatherings of priests and the faithful from Boston to California.

31

From the moment his visit was announced, press speculation focused on whether the cardinal would meet with the American president. Father Coughlin used his radio program to warn the Vatican secretary of state against such a meeting, since it would suggest Vatican support for Roosevelt’s reelection.

32

His listeners responded with a flood of angry letters to the papal delegate in Washington adding their own words of warning. (Lacking formal diplomatic relations with the United States, the Vatican kept a delegate, not a nuncio, in the capital.)

33

Bowing to the pressure, Pacelli waited until two days after the election to see Roosevelt.

Their meeting took place at the president’s family home in Hyde Park, New York. The only record of their conversation comes from Roosevelt’s recollections several years later. What most impressed him, he said, was Pacelli’s seeming obsession with the threat of a Communist takeover in the United States. He sounded, thought the president, much like Father Coughlin. The cardinal kept repeating, “The great danger in America is that it will go communist.” Roosevelt countered that the real danger was that the United States might become fascist.

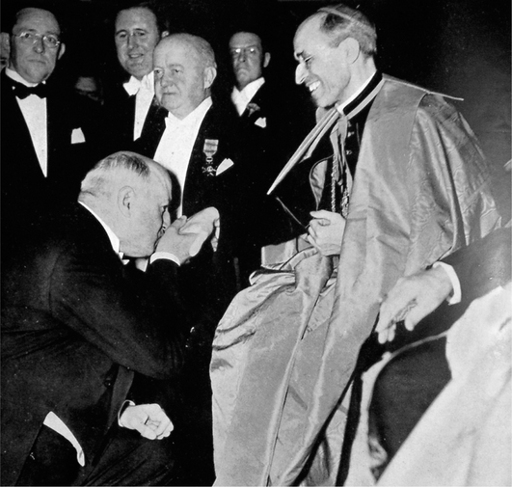

Cardinal Pacelli during his visit to New York City, October 1936

“Mr. President,” replied Cardinal Pacelli, “you simply do not understand the terrible importance of the communist movement.”

“You just don’t understand the American people,” responded Roosevelt.

34

Two days later Pacelli boarded the ocean liner

Count of Savoy

in New York harbor, bound for home.

35

––

ONE NIGHT IN OCTOBER

, while Cardinal Pacelli was still in America, the pope fainted, banging his head against a wooden bedpost as he fell. It was a hint of what was to come. By November, the once-vigorous pope had to be carried to his public audiences in a chair borne aloft by attendants. In early December, with his heart showing signs of frightening weakness, the seventy-nine-year-old pope was confined to bed.

36

The pope’s varicose veins caused him terrible pain, eased a bit by his attendants, who massaged his legs for an hour each day. He spent most of the time in bed, and his doctor visited four times a day.

37

At night the pope’s two old clerical assistants from Milan took turns sitting by his bedside, for he was too uncomfortable to get much sleep. The only regular appointment he still kept was with Cardinal Pacelli, who came by daily as the pope struggled to keep up with all that was going on.

38

The pope was in such agony that Pacelli could barely contain his tears. Pius kept pressing his doctor to tell him how long it would take to get better. “I don’t want you to hide the truth,” he told the tongue-tied physician, who sputtered that he could not say. The pope drank a little milk in the morning, then some clear soup in the afternoon, listening to classical music on his radio. As Christmas approached, he insisted on giving the cardinals their traditional blessing, offered at his bedside. Meanwhile they began to talk, discreetly, about a successor. At a certain point the pope stopped asking his doctor when his health would improve. He asked only that God grant him a dignified death.

39

The Vatican put out a series of misleading stories to explain why Pius was bedridden. But when the new year came and he still did not reappear, rumors of his declining health could no longer be brushed off. In early January 1937

L’Osservatore romano

reported that the pontiff suffered from arteriosclerosis and weak blood circulation. There was some hope, according to the Vatican newspaper, that the pope’s condition might improve, but given the nature of the disease and the pope’s age, a “certain prudence” was called for.

40

The pope was less sanguine. Every night, at his request, his secretary read him historical accounts of the final days of previous popes.

“It’s time to go home,” he said wearily. “We need to prepare the bags.”

41

As he rested, he gazed at the painting across from his bed. It showed Andrea Avellino, patron saint of the good death. In pain and weakened by age, Pius chafed at his helplessness. The strong, self-assured, demanding pope who had so terrorized those around him seemed to be rapidly receding. But as Pius XI might have said, God works in strange ways. The pope’s greatest battle was yet to come.

PART THREE

MUSSOLINI, HITLER,

AND THE

JEWS

C

HAPTER

NINETEEN

ATTACKING HITLER

N

O ONE THOUGHT A CONCLAVE COULD BE FAR OFF. CARDINALS SIZED

one another up. American journalists snooped around the Vatican with wads of cash, eager to find someone to tip them off the moment the pope died.

1

Mussolini’s ambassador, Bonifacio Pignatti, kept him abreast of the behind-the-scenes maneuvering. In Italy, he reported, “faith in the Duce is absolute and beyond discussion in all of the Episcopal hierarchy and clergy”; Pius XI’s successor “would have to be crazy” to upset the Church’s good relations with the Fascist government. But outside Italy things were different, he warned: the Third Reich’s “immorality trials” of Catholic clergy had united cardinals worldwide against the Nazis. Nor were they pleased by the assault on Catholic parochial schools and the recent closing of the Catholic daily press. The deification of Hitler and German blood, along with the growth of Hitler Youth at the expense of Catholic youth groups, only made matters worse. Pignatti worried that the cardinals’ hostility toward Hitler was affecting their attitude to Mussolini. While Italy’s cardinals would surely want a pope who would support the Vatican’s alliance with Mussolini, the non-Italians might try to elect someone less enamored of Fascism.

2

Surprisingly, the pope began to get better. Those cardinals who had begun packing their bags for a trip to Rome found themselves unpacking. Pius would never again enjoy good health, but he would recover enough to resume his most important duties, meeting with the heads of the Curia congregations and eventually even resuming his public audiences, albeit at a reduced rate. In late March 1937 Cardinal Baudrillart, seeing the pope for the first time in months, observed that he “seems very much changed to me, much thinner, his face emaciated and wrinkled. The expression on his face is softer.”

On Easter Sunday, the pontiff made a dramatic return to public view, borne aloft in his

sedia gestatoria

in a cortege that snaked through a packed St. Peter’s Basilica. He looked weak, his face ashen. Many cried with joy, having thought they would never see him again. The pope’s eyes, too, were moist as he traversed the cavernous basilica. After the mass, his attendants carried him to the external balcony, where he looked out at the crowd that filled St. Peter’s Square, awaiting his blessing. “The hour came,” recalled Baudrillart. “The pope’s voice remains strong and clear. The world, this sad world, is blessed!”

3

A few days later, when the pope entered his library for the first time since his illness, he could barely contain his tears. Many nights as he lay awake he had wondered if he would ever see it again. In the weeks ahead, as the pains in his legs were partly relieved by elastic stockings and regular massages, the pope arrived for his public audiences in a chair borne aloft on two poles. Inside his apartment, he used a wheelchair. In those brief but precious moments when he got out into the gardens, he walked haltingly with a cane. He now held his first appointment of the day at ten

A.M.

and took a long nap after lunch. On Mondays he stayed in bed all day. At night he relaxed by listening to music on the radio.

4

THE VATICAN

’

S RELATIONS WITH

Hitler were only getting worse. The show trials of German priests were generating sensational press coverage, and the number of children in Catholic schools was diminishing to

the vanishing point. Yet the Vatican’s alliance with Mussolini remained strong. Months after Italian troops marched into Addis Ababa, Italians still swelled with patriotic pride. “Mussolini’s smile is like a flash of the Sun god,” wrote one fawning Italian journalist, “expected and craved because it brings health and life.”

5

Italy’s most prominent Catholic newspaper,

L’Avvenire d’Italia

, and the Vatican’s

L’Osservatore romano

both expressed enthusiastic support for the regime.

6

Mussolini’s ties with Hitler had done little to lessen the Vatican’s support for him, but outside Italy the dictator’s luster was fading. In February, Italy’s ambassador to the United States worriedly reported the change: Americans were coming to see Fascism and Nazism as two faces of the same totalitarian coin, and Americans despised the Nazis.

7

But Mussolini still enjoyed Italian Americans’ enthusiastic support. As a result, politicians in areas with large Italian American populations were reluctant to criticize him. In 1937 New York’s mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, told a Jewish group that Hitler’s effigy should be put in a chamber of horrors at the World’s Fair, and a year later he branded the Führer a “contemptible coward.” But even though Italy’s anti-Semitic laws were instituted in 1938, La Guardia—whose Italian mother came from a Jewish family—dared say nothing critical of the Duce until 1940, when Italy invaded France and entered World War II on the Nazis’ side.

8

In early 1937 a German reporter arrived at the Palazzo Venezia to interview Mussolini. At the far end of the Hall of the Map of the World, framed by the enormous marble fireplace, sat his host. The Duce sprang to his feet, standing ramrod straight, and extended his right arm in Roman salute. He asked his German visitor how the Führer was. “Very well,” replied the reporter, who was struck by Mussolini’s vigor. His “Caesarean face” appeared to have gotten younger, and the wrinkles around his eyes had disappeared.

An epic battle was about to begin, the Duce told him. Communism was threatening to destroy Europe. The democracies had become the centers of infection, “propagators of the communist bacillus.” Europe was at a turning point. “This is the age of strong individualities and

predominant personalities,” Mussolini explained. “Democracies are sand, shifting sand. Our political ideal of the State is a rock, a granite peak.” Only Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany could save Europe.

9