The Proud Tower (43 page)

Authors: Barbara Tuchman

The Kaiserin remarked that she had not seen her husband so annoyed for a long time as over the sudden intrusion—into a domain he considered his own—of “Nicky,” the Czar, whom he was accustomed to patronize and advise in voluble letters in English signed “Willy.” Whether or not he had planned some similar statement from Jerusalem, the real bite was, as his friend Count Eulenburg said, that he “simply can’t stand someone else coming to the front of the stage.”

Assuming at a glance that the proposal was one for “general disarmament,” and immediately seeing the results in personal terms, the Kaiser dashed off a telegram to Nicky. Imagine, he reproached, “a Monarch holding personal command of his Army, dissolving his regiments sacred with a hundred years of history … and handing over his towns to Anarchists and Democracy.” Nevertheless he felt sure the Czar would be praised for his humanitarian proposal, “the most interesting and surprising of this century! Honor will henceforth be lavished upon you by the whole world; even should the practical part fail through difficulties of detail.” He littered the margins of ensuing correspondence with

Aha!

’s and

!!

’s and observations varying from the astute to the vulgar, the earliest being the not unperceptive thought, “He has put a brilliant weapon into the hands of our Democrats and Opposition.” At one point he compared the proposal to the Spartans’ message demanding that the Athenians agree not to rebuild their walls; at another he suddenly scribbled the rather apt query, “What will Krupp pay his workers with?”

Germany did not have the motive and the cue for peace that Russia had: straitened circumstances. Under-developed industry was not a German problem. When Muraviev in Berlin told Count Eulenburg that the guiding idea behind the Russian proposal was that the yearly increases would finally bring the nations to the point of

non possumus

, he could not have chosen a worse argument.

Non possumus

was not in the German vocabulary. Germany was bursting with vigor and bulging with material success. After the unification of 1871, won by the sword in the previous decade of wars, prosperity had come with a rush, as it had in the United States after the Civil War. Energies were let loose on the development of physical resources. Germany in the nineties was enjoying the first half of a twenty-five-year period in which her national income doubled, population increased by 50 per cent, railroad-track mileage by 50 per cent, cities sprang up, colonies were acquired, giant industries took shape, wealth accumulated from their enterprises and the rise in employment kept pace. Albert Ballin’s steamship empire multiplied its tonnage sevenfold and its capital tenfold in this period. Emil Rathenau developed the electrical industry which quadrupled the number of its workers in ten years. I. G. Farben created aniline dyes; Fritz Thyssen governed a kingdom of coal, iron and steel in the Ruhr. As a result of a new smelting process making possible the utilization of the phosphoric iron ore of Lorraine, Germany’s production of coal and steel by 1898 had increased four times since 1871 and now surpassed Britain’s. Germany’s national income in that period had doubled, although it was still behind Britain’s, and measured per capita, was but two-thirds of Britain’s. German banking houses opened branches around the world, German salesmen sold German goods from Mexico to Baghdad.

German universities and technical schools were the most admired, German methods the most thorough, German philosophers dominant. The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute was the leading laboratory for chemical research in the world. German science boasted Koch, Ehrlich and Roentgen, whose discovery of the X ray in 1895 was, however, as much a product of his time as of his country, for in 1897–99 in England J. J. Thomson had discovered the electron, and in France the Curies the release of energy by radioactivity. German professors expounded German ideals and German culture, among them Kuno Francke at Harvard, who pictured Germany pulsing with “ardent life and intense activity in every field of national aspirations.” He could barely contain his worship of the noble spectacle:

“Healthfulness, power, orderliness meet the eye on every square mile of German soil.” No visitor could fail to be impressed by “these flourishing, well-kept farms and estates, these thriving villages, these carefully replenished forests,… these bursting cities teeming with a well-fed and well-behaved population,… with proud city halls and stately courthouses, with theatres and museums rising everywhere, admirable means of communication, model arrangements for healthy recreation and amusement, earnest universities and technical schools.” The well-behaved population was characterized by its “orderly management of political meetings, its sober determination and effective organization of the laboring classes in their fight for social betterment” and its “respectful and attentive attitude toward all forms of art.” Over all reigned “the magnificent Army with its manly discipline and high standards of professional conduct,” and together all these components gave proof of “the wonderfully organized collective will toward the higher forms of national existence.” The mood was clearly not one amenable to proposals of self-limitation.

The sword, as Germany’s historians showed in their explanations of rise, was responsible for Germany’s greatness. In his

History of Germany in the Nineteenth Century

, published in five volumes and several thousand pages over a period of fifteen years in the eighties and nineties, Treitschke preached the supremacy of the State whose instrument of policy is war and whose right to make war for honor or national interest cannot be infringed upon. The German Army was the visible embodiment of Treitschke’s gospel. Its authority and prestige grew with every year, its officers were creatures of ineffable arrogance, above the law, who inspired an almost superstitious worship in the public. Any person accused of insult to an officer could be tried for the crime of indirect

lèse majesté.

German ladies stepped off the sidewalk to let an officer pass.

Radio Times Hulton Picture Library

Lord Salisbury (

Photo Credit 5.1

)

By Courtesy of the Trustees of the Tate Gallery, London

Lord Ribblesdale (portrait by Sargent, 1902) (

Photo Credit 5.2

)

By permission of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wolfe Fund, 1927

The Wyndham sisters: Lady Elcho, Mrs. Tennant, and Mrs. Adeane

(portrait by Sargent, 1899) (

Photo Credit 5.3

)

By Country Life from H. A. Tipping, English Homes

Chatsworth (

Photo Credit 5.4

)

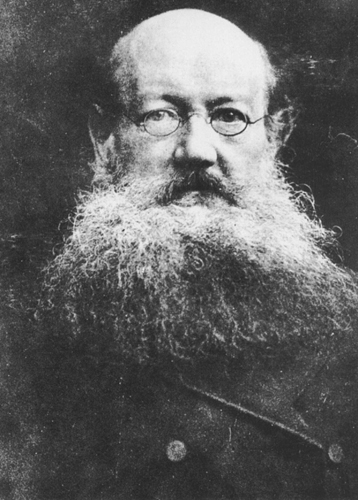

Brown Brothers

Prince Peter Kropotkin (

Photo Credit 5.5

)

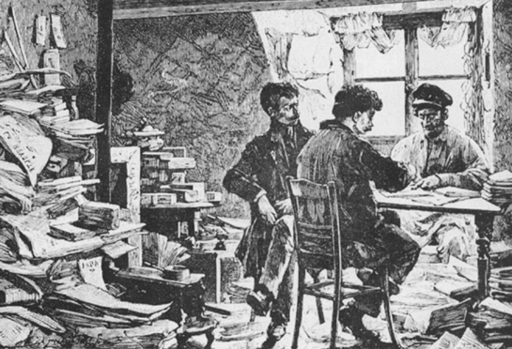

Editorial office of

La Révolte

(

Photo Credit 5.6

)

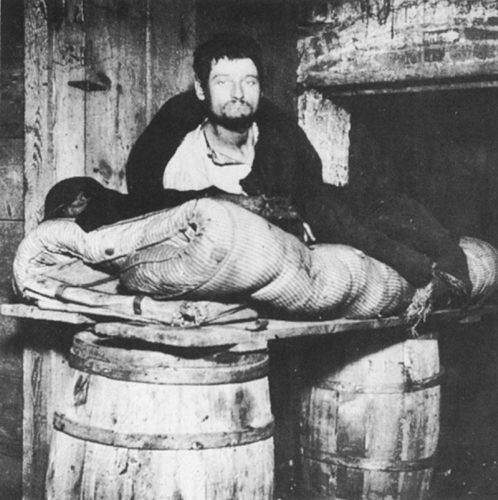

Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York

“Slept in That Cellar Four Years” (photograph by Jacob A. Riis, about 1890) (

Photo Credit 5.7

)