The Proud Tower (44 page)

Authors: Barbara Tuchman

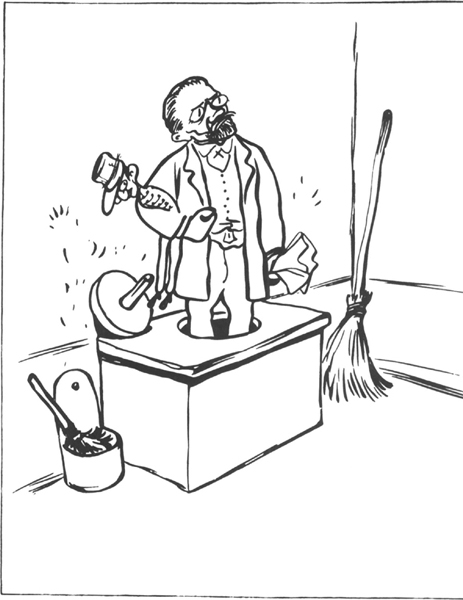

“Lockout” (drawing by Théophile Steinlen; signed “Petit Pierre”)

(

Photo Credit 5.8

)

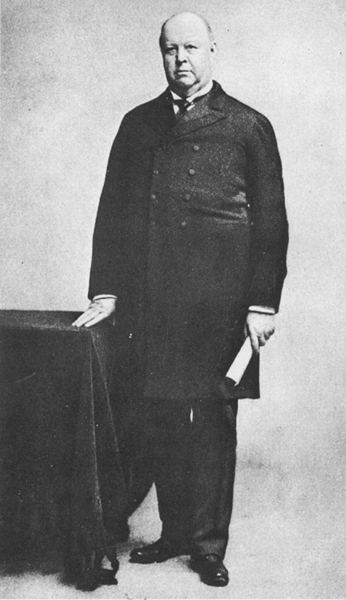

Thomas B. Reed

(

Photo Credit 5.9

)

Brown Brothers

Captain (later Admiral) Alfred Thayer Mahan (

Photo Credit 5.10

)

Brown Brothers

Charles William Eliot (

Photo Credit 5.11

)

Samuel Gompers (

Photo Credit 5.12

)

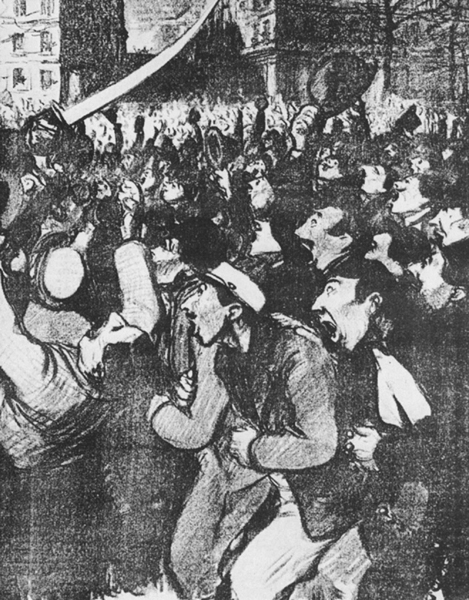

The mob during Zola’s trial (drawing by Théophile Steinlen) (

Photo Credit 5.13

)

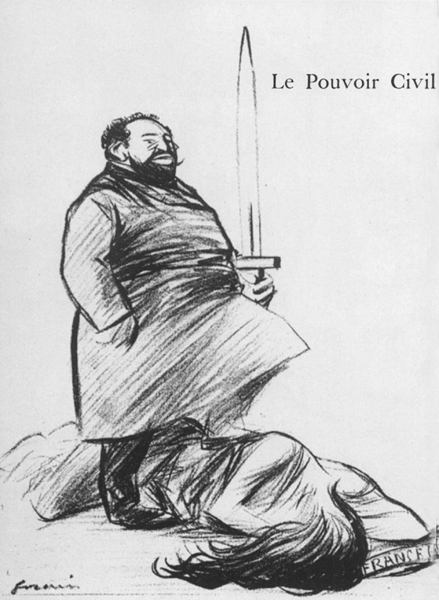

The “Syndicate” (drawing by Forain)

(

Photo Credit 5.14

)

L’Affaire Dreyfus.

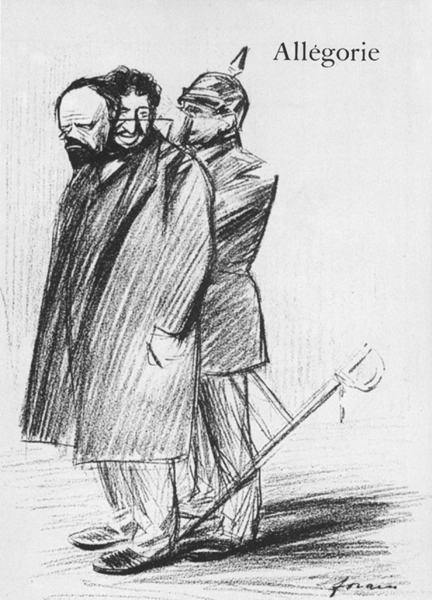

“Allegory” (drawing by Forain) (

Photo Credit 5.15

)

Coucou, le voilà!

La Vérité sort de son puits.

“Truth Rising from Its Well” (drawing by Caran d’Ache) (

Photo Credit 5.16

)

In 1891 the Alldeutsche Verband (Pan-German League) was founded, whose program was the union of all members of the German race, wherever they resided, in a Pan-German state. Its core was to be a Greater Germany incorporating Belgium, Luxemburg, Switzerland, Austria-Hungary, Poland, Rumania and Serbia which, after this first stage was accomplished, would extend its rule over the world. The League distributed posters for display in shop windows reading, “

Dem Deutschen gehört die Welt

” (“The world belongs to Germans”). In a simple statement of purpose Ernst Hasse, founder of the League, declared, “We want territory even if it belongs to foreigners, so that we may shape the future according to our needs.” It was a task his countrymen felt equal to.

Any outbreak of fighting among the nations, as in the Sino-Japanese War of 1895 or the Spanish-American War, stirred in the Germans a powerful desire to mix in. Admiral von Diederichs, in command of the German Pacific Squadron at Manila Bay, was edging for a quick grab at the Philippines, and only Admiral Dewey’s red-faced roar, “If your Admiral wants a fight he can have it now!”—silently if conspicuously supported by movements of the British squadron—made him draw back. “To the German mind,” commented Secretary Hay, “there is something monstrous in the thought that a war should take place anywhere and they not profit by it.” Dewey, understandably, thought they had “bad manners.” “They are too pushing and ambitious,” he said, “they’ll overreach themselves someday.”

At the top of the German state was a government essentially capricious. Ministers were independent of Parliament and held office at the will of a sovereign who referred to the members of the Reichstag as “sheepsheads.” Since government office was confined to members of the aristocracy and the premise of a political career was unqualified acceptance of Conservative party principles, the doors were closed to new talent. “Not even the tamest Liberal,” regretted the editor of the

Berliner Tageblatt

, “had any chance of reaching a post of the slightest distinction.” After the Kaiser’s dismissal of Bismarck in 1890, no one of active creative intelligence held an important post. The Chancellor, chosen because he was such a relief from Bismarck, was Prince Chlodwig zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst, a gentle-mannered, fatherly Bavarian whose motto, it was said, was: “Always wear a good black coat and hold your tongue.” The Foreign Minister was Count Bernhard von Bülow, an elegant gentleman of extreme suavity and self-importance and a manner so well oiled that in conversation and correspondence he seemed always to be rubbing his hands like a rug merchant. He used to scribble notes on his shirt cuffs for fear of forgetting the least of His Majesty’s wishes. In an effort to catch the effortless parliamentary manner of Balfour he practiced holding onto his coat lapels before the bathroom mirror, coached by an attaché from the Foreign Office. “Watch,” murmured a knowing observer in the Reichstag when Bülow rose to speak, “here comes the business with the lapels.”

Behind Bülow in control of foreign policy was the invisible Holstein who in the manner of Byzantine courts exercised power without nominal office. He regarded all diplomacy as conspiracy, all overtures of foreign governments as containing a concealed trick, and conducted foreign relations on the premise of everyone’s animosity for Germany. The interests of a Great Power, he explained to Bülow, were not necessarily identical with the maintenance of peace, “but rather with the subjugation of its enemies and rivals.” Therefore “we must entertain the suspicion” that the Russian objective was “rather a means to power than to peace.” Bülow agreed. His instructions to envoys abroad breathed of pitfalls and plots and treated Muraviev’s agenda as if it were a basket of snakes. It would be desirable, he wrote to his Ambassador in London, “if this Peace and disarmament idea … were wrecked on England’s objections without our having to appear in the foreground,” and he trusted the Ambassador to guide the exchange of views with Mr. Balfour toward that end.

Mr. Balfour, the acting Foreign Secretary for Lord Salisbury, was not an entirely suitable victim for Bülow’s manipulations. However skeptical of results, the British Government, unlike the German, did not feel threatened by an international conference and did not intend to bear the brunt of wrecking it. Moreover, public enthusiasm could not be flouted in England. In the four months following the Czar’s manifesto, over 750 resolutions from public groups reached the Foreign Office welcoming the idea of an international conference and expressing the “earnest hope,” in the words of one of them, that Her Majesty’s Government would exert their influence to ensure its success “so that something practical may result.” The resolutions came not only from established peace societies and religious congregations but from town and shire meetings, rural district committees, and county councils, were signed by the Mayor, stamped with the county seal, forwarded by the Lord Lieutenant. Some without benefit of official bodies came simply from the “People of Bedford,” “Rotherhead Residents” or “Public Meeting at Bath.” Many came from local committees of the Liberal party, although Conservative groups were conspicuously absent, as were Church of England congregations. All the Nonconformist sects were represented: Baptists, Methodists, Congregationalists, Christian Endeavor, Welsh Nonconformists, Irish Evangelicals. The Society of Friends collected petitions with a total of 16,000 signatures. Bible associations, adult schools, women’s schools, the National British Women’s Temperance Association, the Manchester Chamber of Commerce, the West of Scotland Peace and Arbitration Association, the Humanitarian League, the Oxford Women’s Liberal Association, the General Board of Protestant Dissenters, the Mayor of Leicester, the Lord Mayor of Sheffield, the Town Clerk of Poole, were among the signatories.