The Proud Tower (50 page)

Authors: Barbara Tuchman

The pistol represented, perhaps, less a lawless mind than the creed of the time that life was a fight. No one felt it more deeply than Roosevelt. He despised Tolstoy’s “foolish theory that men should never make war,” for he believed that “the country that loses its capacity to hold its own in actual warfare will ultimately show that it has lost everything.” He was infuriated when the peace advocates equated progress in civilization with “a weakening of the fighting spirit”; such a weakening, as he saw it, invited the destruction of the more advanced by the less advanced. He confused the desire for peace with physical cowardice and harped curiously on this subject: “I abhor men like [Edward Everett] Hale and papers like the

Evening Post

and the

Nation

in all of whom there exists absolute physical dread of danger and hardship and who therefore tend to hysterical denunciation and fear of war.” He deplored what seemed to him, as he looked around, a “general softening of fibre, a selfishness and luxury, a relaxation of standards” and especially “a spirit such as that of the anti-imperialists.” “That’s my man!” the Kaiser used to say whenever Roosevelt’s name was mentioned.

No President had a more acute sense of his own public relations. When Baron d’Estournelles came in 1902 to beg him to do something to breathe life into the Arbitration Tribunal, Roosevelt listened. “You are a danger and a hope for the world depending on whether you support aggression or arbitration,” d’Estournelles said. “The world believes you incline to the side of violence. Prove the contrary.”

“How?” the President asked.

“By giving life to the Hague Court.” Roosevelt promptly instructed Secretary Hay to find something to submit for arbitration and Hay obligingly uncovered an old quarrel between the United States and Mexico over church property, the first dispute to activate the Tribunal. Having been Secretary of State during the Hague Conference and sympathetic to arbitration, Hay wanted to build up the prestige of the Tribunal and now arranged to divert to it the dispute over Venezuela’s debts. Fearing that the President might accept a German proposal to act as individual mediator in this affair, he strode up and down the room exclaiming, “I have it all arranged, I have it all arranged. If only Teddy will keep his mouth shut until tomorrow noon!” That objective being happily accomplished, the Tribunal received another important case.

Arbitration treaties between individual countries slowly made progress. England and France agreed on one when they joined in the Entente of 1904 and Norway and Sweden concluded another when Norway, without the firing of a shot, became an independent state in 1905—an event hailed in itself as evidence that man was making progress. Two other international disputes of the time, the Dogger Bank affair between Russia and England and the affair of Venezuela’s debts, were referred to the Arbitration Tribunal, whose existence proved an invaluable means of saving face and satisfying public opinion. The Hague idea seemed to be putting on flesh.

In the summer of 1904 the Interparliamentary Union, meeting at the St. Louis Fair, adopted a resolution asking the President of the United States to convene a Second Peace Conference to take up the subjects postponed at The Hague and to carry arbitration forward toward the goal of a permanent court of international law. At the White House, Roosevelt accepted the resolution in person, as well as a visit from Baroness von Suttner, who had a private talk with him on “the subject so dear to my heart.” She found him friendly, sincere and “thoroughly impressed with the seriousness of the matter discussed.” According to her diary he said to her, “Universal peace is coming; it is certainly coming—step by step.” As the most unlikely remark of the epoch, it illustrates the capacity of true believers to hear what they want to hear.

Roosevelt felt the glamour of a world role and as convener of the Peace Conference considered himself no less fitted than the Czar. Accordingly on October 21, 1904, Hay instructed American envoys to propose that the nations reconvene at The Hague. That the Second Conference, like the First, was called while a war was in progress need not, he suggested, be considered an ill omen.

The nations accepted on condition that the Conference should not be convened until the Russo-Japanese War was over. No sooner was it over, however, than the Moroccan crisis erupted. Again President Roosevelt played a decisive role and was able to exercise his influence, this time privately, to persuade the Kaiser to agree to an international conference on Morocco. Held at Algeciras in January, 1906, with the United States as a participant, it proved to be a discomfiture for Germany, leaving her more bellicose than before. International tensions were not eased.

Three months before Algeciras, in October, 1905, the keel of

H.M.S. Dreadnought

, first of her class, was laid. With guns and armor plate manufactured by separate ordnance firms, she was ready for trials in an unprecedented burst of speed and secrecy, a year and a day later, achieving the greatest of military advantages—surprise. Designed by Fisher, the

Dreadnought

was larger, swifter, more heavily gunned than any battleship the world had ever seen. Displacing 18,000 tons, carrying ten 12-inch guns, and powered by the new steam-turbine engines, it made all existing fleets, including Germany’s, obsolete, besides demonstrating Britain’s confidence and capacity to rebuild her own fleet. Germany would now not only have to match the ship but dredge her harbors and widen the Kiel Canal.

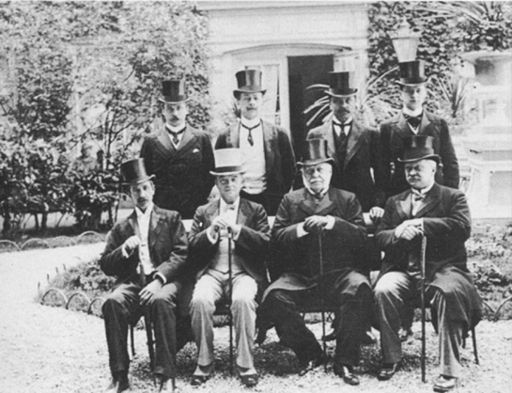

Courtesy the Royal Archives, The Hague

British delegation to The Hague, 1899. Front row, from left to right: Ardagh; Fisher; Pauncefote; Sir Henry Howard, Minister to The Hague. Arthur Peel is first on the left in the back row. (

Photo Credit 5.17

)

Brown Brothers

PARIS EXPOSITION, 1900 Porte Monumentale

Palace of Electricity (

Photo Credit 5.18

)

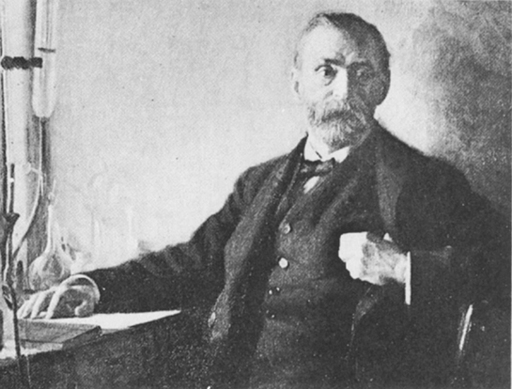

Alfred Nobel (portrait by E. Osterman) (

Photo Credit 5.20

)

Bertha von Suttner (

Photo Credit 5.21

)

Brown Brothers

The Krupp works at Essen, 1912 (

Photo Credit 5.22

)

Courtesy Dr. Franz and

Alice Strauss

Richard Strauss, 1905 (

Photo Credit 5.23

)