The Proud Tower (51 page)

Authors: Barbara Tuchman

Friedrich Nietzsche, Weimar, 1900 (drawing by Hans Olde)

(

Photo Credit 5.24

)

A beer garden in Berlin (

Photo Credit 5.25

)

Brown Brothers

Nijinsky as the Faun (design by Léon Bakst) (

Photo Credit 5.26

)

Radio Times Hulton Picture Library

Arthur James Balfour, about 1895 (

Photo Credit 5.27

)

Brown Brothers

Coal strike, 1910 (

Photo Credit 5.28

)

CAPITAL

Brown Brothers

Seamen’s strike, 1911 (

Photo Credit 5.29

)

AND LABOUR

The Mansell Collection, London

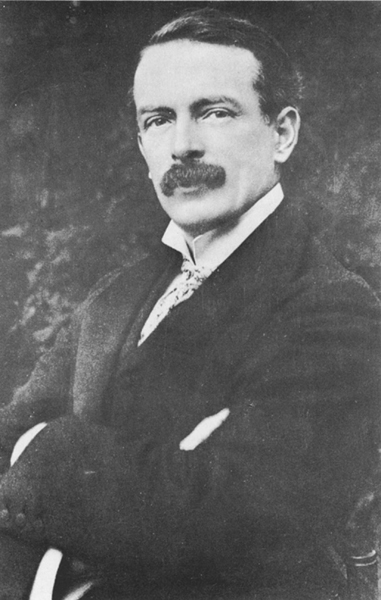

David Lloyd George, about 1908 (

Photo Credit 5.30

)

August Bebel (

Photo Credit 5.31

)

Keir Hardie (

Photo Credit 5.32

)

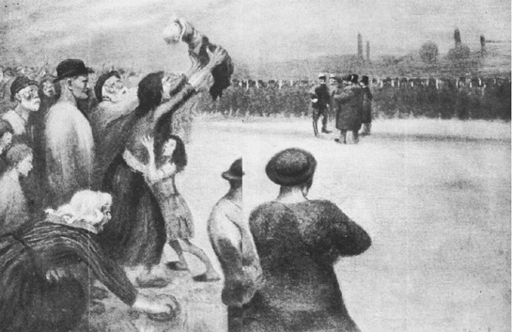

“Strike” (oil painting by Théophile Steinlen) (

Photo Credit 5.33

)

Jean Jaurès (

Photo Credit 5.34

)

In Fisher’s mind, as in Clemenceau’s, there was but one adversary. Half jokingly in 1904 he shocked King Edward by suggesting that the growing German Fleet should be “Copenhagened,” that is, wiped out by surprise bombardment, evoking the King’s startled reply, “My God, Fisher, you must be mad!” At Kiel in the same year, the Kaiser upset Bülow by publicly ascribing the genesis of his Navy to his childhood admiration of the British Fleet, which he had visited in company with “kind aunts and friendly admirals.” To give such sentimental reasons for a national development for which the people were being asked to pay millions, Bülow scolded, would not encourage the Reichstag to vote credits. “Ach, that damned Reichstag!” was the Kaiser’s reply.

Invitations to The Hague meanwhile had been reissued not by Roosevelt but by the Czar, who felt the necessity of regaining face. The upstart American republic had intervened enough. In September, 1905, as soon as his war was over, the hint was conveyed to Washington that he wished the right to call the Conference himself. Roosevelt amiably relinquished it. The Treaty of Portsmouth, which in a few months was to bring him the Nobel Peace Prize, had, he felt, been enough of a good thing. “I particularly do

not

want to appear as a professional peace advocate … of the Godkin or Schurz variety,” he wrote to his new Secretary of State, Elihu Root.

*

His withdrawal did not please the peace advocates. Russia, as one of them said, was “not in the van of civilization.” This became strikingly apparent upon the outbreak of the Russian revolution of 1905. Forced by the crisis to grant a constitution and a parliament, the Czar repudiated the action as soon as his regime regained control, and dissolved the Duma to the horror of foreign liberal opinion.

The time seemed not on the whole propitious for a Peace Conference, but one encouraging development was a change of government in England which brought the Liberals, the traditional party of peace, to power. The new Prime Minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, known to all as C.-B., was a solid round-headed Scot of a wealthy mercantile family who had made himself unpopular in Court and in Society by denouncing British concentration camps in the Boer War as “methods of barbarism.” Nevertheless, King Edward, forced to become acquainted, discovered him to be indeed, as a mutual friend had promised, “so straight, so good-tempered, so clever and so full of humor” that it was impossible not to like him. C.-B. had the wit, tact and worldly wisdom that the King appreciated and the two gentlemen, who had a number of tastes in common, soon found each other congenial. They both went annually to Marienbad for the cure, they both loved France and shared a special friendship with the Marquis de Galliffet. Though a Liberal, C.-B. was, to the royal surprise, “quite sound on foreign politics.” He spoke the most fluent French of any Englishman, delighted to shop in Paris, to eat French food and read French literature, Anatole France being one of his favorites.