The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine (10 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine Online

Authors: James Le Fanu

Doll and Bradford Hill promptly published their first study in the

British Medical Journal

on 30 September 1950, and its distinguishing features merit some comment. Firstly, the âdose-response' relationship between smoking and lung cancer was very subtle and this could readily have been obscured were it not for the rigorous way in which possible sources of bias had been anticipated and eliminated. Secondly, it is impossible to convey, without publishing the paper in full, the lucidity of its exposition, so its weighty conclusion seems unarguable. Put another way, it is very difficult to appreciate the novelty of their paper. The source of reliable knowledge in medicine had always been in the biological and physical sciences. Now, in the face of considerable scepticism, statistical methods had âtriumphantly' (one can justifiably say) been demonstrated to be capable of providing a new and genuine insight into the nature of disease.

Nonetheless, it would take more than this for people to stop smoking. Bradford Hill looked around for some other way by which the link could be demonstrated and â in a masterly stroke of imagination â invented an entirely new method of investigation. The âcase-control' study he had just conducted was âretrospective', in that it tried to make sense of something that had happened in the past, how the habits of a lifetime may have contributed to one disease in particular. But if the association between lung cancer and smoking was valid, he should get

the same result looking forward, starting with a large number of men and women, asking them pertinent questions about their lives, including their smoking habits, and then sitting back and watching what happened to them over the years. They would die from diverse diseases, but the smokers should die in disproportionate numbers from lung cancer. The elegance of this âprospective' or âcohort' study is the simplicity of the open-ended question â âWhat do smokers die of?' â to which time will inevitably provide an answer.

Bradford Hill chose as his cohort the 60,000 doctors on the Medical Register, who were likely to be reliable in answering the questions posed to them. There could be no more forceful way of bringing home to the profession the hazards of tobacco â which hopefully would then be passed on to patients â than by incorporating them in this scientific endeavour to provide further proof that smoking caused lung cancer. In November 1951 Bradford Hill wrote a letter to the

British Medical Journal

which was published under the headline âDo You Smoke?':

Last week I sent a letter personally to every man and woman on the Medical Register of the UK asking them to help me. I asked them to fill in a very simple form about their smoking habits.

This, I think, is a new method of approach. May I therefore repeat my appeal through your column? If every doctor, whatever his field of work, will spare only a moment or two this research can be founded on a firm basis and in time give, I believe, firm and important answers. I am, etc.

35

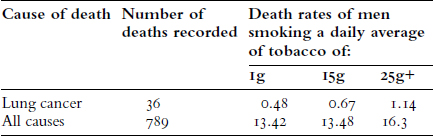

In a short period, a mere two and a half years, Bradford Hill had his answer. Of the 40,000 doctors who replied to the questionnaire, 789 had subsequently died, a mere 36 from lung

cancer. But when the smoking habits of the deceased were tabulated (see below), lung cancer was the only disease in which there was a clear dose-response relationship â the more tobacco smoked, the greater the death rate, rising from 0.48 per 1,000 doctors smoking 1g of tobacco daily, to 0.67 for those smoking 15g, to 1.14 for those smoking 25g or more, compared to those who had died from âall causes', in whom there was no gradient with increase in smoking habit.

36

Mortality rate per 1,000 male doctors in relation to the most recent amount of tobacco smoked

(From R. Doll and A. Bradford Hill, âThe Mortality of Doctors in Relation to Their Smoking Habit',

BMJ

, 26 June 1954, pp. 1451â5.)

The final verdict on the statistical proof of the causative role of tobacco in lung cancer can be found in a reply from Bradford Hill to the following small item in

The Lancet

of 14 December 1957:

Yesterday the morning post brought an embarrassing revelation from my husband's past. It was an innocent-looking letter from the Medical Research Council and ran: âDear Doctor: In 1951 you stated that you smoked an average of three cigarettes a day . . .'

Three

cigarettes a day! When I met him, around that time,

thirty-three

would have been a conservative estimate. The mean had hovered around there ever since, plus or minus a few standard deviations. We sat dumbfounded, our bacon cooling uneaten. I broke the silence first. âWhy you hypocritical old . . .'

Then I was aware that this was superfluous. My husband stared before him, automatically buttering toast.

âHow could I,' he began brokenly, âhow could I say such a thing?'

But already it was obvious. My husband is a heavy smoker except when Giving Up Smoking. This happens three or four times a year and lasts anywhere from half an hour to two horrible weeks. During these interludes he is very virtuous, and impossible to live with. Clearly the questionnaire had caught him whilst he was Giving Up Smoking or, more accurately, tapering off.

There it is. Three cigarettes a day. It makes you think. I mean, statistical methods are so reliable these days. Isn't it appalling that they have to depend on people?

Bradford Hill's reply was couched in his customary elegant prose:

Sir: I must hasten to correct any marital disharmony that in my innocence I may have promoted. If in November 1951 the husband of your correspondent was temporarily smoking three cigarettes a day, then he truthfully answered the question I put to him. For I had asked him, clearly and deliberately, what are your present habits? Before popping the question I had realised that the present is not invariably a certain guide to the past (or future), that manic and depressive phases may succeed one another, but I had also realised,

as alas, your correspondent does not, that these âerrors' of classification would inevitably

reduce

not exaggerate any association between smoking habits and mortality that I might subsequently find. In short the observation in this enquiry that mortality from lung cancer in âheavy' smokers has been some 20 times the rate in non-smokers

understates

the facts of life. A pity but there it is.

37

In fact âtwenty times' turned out to be just about right. In 1993 Sir Richard Doll, during a special celebration to mark his own eightieth birthday, summarised the results of the famous Doctor Study forty years on. Almost half â 20,000 â of the doctors who had answered the original questionnaire back in 1951 had died, of whom 883 had succumbed to lung cancer. There is a memorable simplicity in the final conclusion. Those smoking twenty-five or more cigarettes a day have a twenty-five-fold increased risk of lung cancer compared to non-smokers.

38

Bradford Hill's twin achievements of 1950, demonstrating the curability of tuberculosis and the preventability of lung cancer, are impressive enough on their own account, but the true significance â which became ever more apparent as the years passed â was even greater. He was naturally â if, as ever, modestly â conscious of the nature of his legacy, which he discussed in two public lectures fifteen years later in 1965, which might justly be considered his apotheosis: âReflections on the Controlled Clinical Trial' and âThe Environment and Disease: Association or Causation?'

39

,

40

We start with âReflections'. âIt is not far off twenty years since the MRC published the results of the [first] trial of streptomycin that set off the population explosion of clinical trials,'

Bradford Hill observed, adding, âover the last twelve months alone they have extended from a treatment for herpes simplex to a low-fat diet in myocardial infarction, from drugs in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome to prophylactic penicillin for comatose patients.' The popularity of the randomised controlled trial obviously lay in its unique ability to provide answers to the sort of questions that doctors ask themselves every day â âDoes this treatment work better than that?' â but crucially the questions were posed and resolved in a manner â the experiment â almost synonymous with science itself. The RCT thus came to be seen as the only âscientific' way of resolving these questions and so, almost by definition, superior to any other form of acquiring knowledge, such as âclinical experience'. In this way the RCT became the âdominant' discourse of post-war medicine. This, as Bradford Hill acknowledged from his own personal experience, was not necessarily a good thing, as statistics have an equal, or even greater, capacity to variously mislead, obscure or in some other way subvert the truth as to clarify it.

I am faced with trials [of drug treatment] on such an ill-defined or undefined pot-pourri of patients that I can but hopelessly speculate on who got what, when and usually why. These poorly conducted trials not only tell us nothing but may be dangerously misleading â particularly when their useless data are spuriously supported by all the latest statistical techniques and jargon.

Such aberrations apart, Bradford Hill maintained that there was simply no alternative to the RCT in evaluating new treatments and challenging the efficacy of the old.

Nonetheless there have been dissenting voices, particularly

recently, about the validity and especially the trustworthiness of the conclusions from such trials. They are, it is argued, insufficiently sensitive to variations in the range of symptoms of disease and thus the responsiveness to treatment. There have been many instances when they have produced the âwrong' result, which was subsequently overturned, but not before the powerful influence of the original false verdict had misdirected medicine down a blind alley, often for decades. There is concern, too, about the habit of aggregating the results of many trials to produce a definitive verdict, as if numbers alone could cancel out the falsehoods inherent in poor scientific data. One observer has described this as âA new kind of alchemy . . . arcane, esoteric and mesmerising, that promises not to turn base metal into gold but to transmute statistical sow's ears into scientific silk purses.' Regrettably not all those who have followed in Bradford Hill's footsteps have been gifted with the same degree of intelligence or fastidiousness and so sometimes â perhaps even often â the âclinical wisdom' of doctors assessing the efficacy of treatment based on their own personal experience may, after all, be a better guide to medical practice than the âobjectivity' of the clinical trial.

41

In the second lecture given by Bradford Hill in 1965, âEnvironment and Disease: Association or Causation?', he elaborated with his customary lucidity on the importance of his discovery of smoking as a cause of lung cancer. This had, after all, established a precedent of the utmost importance, which naturally raised the question as to how many other common diseases â strokes, heart diseases, diabetes and so on (the list is virtually limitless) â might similarly be caused by some aspect of the environment or an individual's âlifestyle' which, if identified and modified, would prevent it.

Possible clues were assiduously sought in thousands of studies

looking for âsomething' to distinguish patients with a given disease from healthy controls. Inevitably they turned up interesting observations. For example, people with multiple sclerosis are more likely to be cat lovers, and those with cancer of the pancreas drink more coffee than average, and so on. Given the large number of different diseases and the numerous measurable aspects of an individual's lifestyle, it is possible to generate a virtually infinite number of hypotheses about causation.

But how can one be certain that, for example, keeping cats might cause multiple sclerosis (perhaps because of some transmissible virus) rather than, for example, that those with multiple sclerosis might be more likely to keep cats as company? The possibilities of the case-control study for investigating the causes of disease, given the precedent of smoking and lung cancer, are immense, but so is the danger of drawing false inferences and conclusions. How can one tell?

Bradford Hill formulated a set of criteria that must be fulfilled. They are illustrated here with the example of smoking and lung cancer.

1

The correlation must be biologically plausible: there are cancer-inducing agents in tobacco which, when brought into contact with lung tissue, could cause the disease.

2

The correlation must be strong: the death rate from lung cancer in cigarette smokers is twenty-five times higher than in non-smokers.

3

The correlation must reflect a biological gradient: the more cigarettes that are smoked, the higher the risk of lung cancer.

4

The correlation must be found consistently: thirty-six separate studies examining the relationship between smoking and lung cancer have found a positive correlation.

5

The correlation must hold over time: as cigarette consumption has steadily increased it has been paralleled by a rise in incidence of disease.

6

The association must preferably be confirmed by experiment. If smoking causes lung cancer, then the experiment of stopping smoking should reduce the risk, and the longer the time since stopping smoking, the lower that risk will be.