The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (102 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

Although China is (apart from NATO) the most serious concern for Soviet planners simply because of its size, it is not difficult to imagine Soviet worries about the entire Asian “flank.” In the largest geopolitical sense, it looks as if the age-old tendency of Muscovite/Russian policy, steady territorial expansion across Asia, has come to a halt. The re-emergence of China, the independence (and growing strength) of India, the economic recovery of Japan—not to mention the assertive-ness of many smaller Asian states—has surely put to rest the nineteenth-century fear of a Russia gradually taking control of the entire continent. (The very idea nowadays would make the Soviet general staff blanch with alarm!) To be sure, this would still not prevent Moscow from making marginal gains, as in Afghanistan; but the duration of that conflict and the hostility it has provoked elsewhere in the region merely confirm that any further extensions of Russian territory would be at an incalculable military and political cost. By contrast with the self-confident Russian announcements of its “Asian mission” a century ago, the rulers in the Kremlin now have to worry about Muslim fundamentalism seeping across its southern borders from the Middle East, about the Chinese threat, and about complications in Afghanistan, Korea, and Vietnam. Whatever the number of divisions positioned in Asia, it can probably never seem enough to give “security” along such a vast periphery, especially since the Trans-Siberian Railway is still terribly vulnerable to disruption by an enemy rocket strike, which in turn would have dire implications for the Soviet forces in the Far East.

198

Given the traditional concern of the Russian regime for the safety of the homeland, it is scarcely surprising that Soviet capacities both at sea and in the overseas world are, relatively speaking, much less significant. This is not to deny the very impressive expansion of the Red Navy over the past quarter-century, and the great variety of new and more powerful submarines, surface vessels, and even experimental aircraft carriers which are being laid down. Nor is it to deny the large expansion of the Soviet merchant marine and fishing fleets, and their significant strategical roles.

199

But there is as yet nothing in the USSR’s naval armory which has the striking power of the U.S. Navy’s fifteen carrier task forces. Moreover, once the comparison is between the fleets of the two

alliances

rather than the two superpowers, the sizable contributions of the non-American NATO navies makes an immense difference.

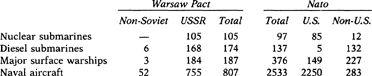

Table 48. NATO and Warsaw Pact Naval Strengths

200

“Even if China is excluded, the Western Allies have twice as many major surface combatants and three times as much naval air power as the Warsaw Pact, and practically as many submarines,” as shown in

Table 48

. If one adds to this the fact that many more of the Warsaw Pact’s large surface warships and submarines are over twenty years old, that its capacity to detect enemy submarines is more limited, and that 75 percent of the Red Navy’s personnel are conscripts (in contrast to the West’s long-service professionals), it is difficult to see how the USSR would be in a position to bid for “command of the sea” in the near future.

201

Finally, if indeed the real purpose of the newer and larger surface warships of the Soviet navy is to form an “ocean bastion” in, say, the Barents Sea to protect its nuclear-missile submarines from Allied attack—that is, if the Russian fleet is being chiefly designed to guard the country’s

strategic deterrent

as it moves offshore

202

—then this clearly gives it little surplus force (apart from its older submarines) to interdict NATO’s maritime lines of communication. By extension, therefore, there would be little prospect of the USSR’s being able to render help to its scattered overseas bases and troop deployments in the event of a major conflict with the West. As it is, despite all of the publicity given to Russia’s penetration of the Third World, it has very few forces

stationed overseas (i.e., outside eastern Europe and Afghanistan), and its only major overseas bases are in Vietnam, Ethiopia, South Yemen, and Cuba, all of which require large amounts of direct financial aid, which seems to be being increasingly resented in Russia itself. It may be that the USSR, having recognized the vulnerability of its Trans-Siberian Railway in the event of a war in which China is involved, is systematically attempting to create a sea line of communication (SLOC), via the Indian Ocean, to its Far East territories. As things are at the moment, however, that route must still appear a very precarious one. Not only are the USSR’s spheres of influence not comparable with the far larger array of American (plus British and French) bases, troops, and overseas fleets stationed across the globe, but the few Russian positions which do exist, being exposed, are very vulnerable to western pressures in wartime. If China, Japan, and certain smaller pro-western countries are brought into the equation, the picture looks even more unbalanced. To be sure, the forcible exclusion of the Soviet Union from the Third World would not be a great blow economically—since its trade, investments and loans in those lands are minuscule compared with those of the West

203

—but that is simply another reflection of its being

less

than a global Power.

Although all of this may seem to be overstating the odds which are stacked against the Soviet Union, it is worth noting that its own planners clearly do think about “worst-case” analyses; and also that its arms-control negotiators always resist any idea of having a mere

equality

of forces with the United States, arguing instead that Russia needs a “margin” to ensure its security against China and to take account of its eight-thousand-mile border. To any reasonable outside observer, the USSR already has more than enough forces to guarantee its security, and Moscow’s insistence upon building ever-newer weapon systems simply induces insecurity in everyone else. To the decision-makers in the Kremlin, heirs to a militaristic and often paranoid tradition of statecraft, Russia appears surrounded by crumbling frontiers—in eastern Europe, along the “northern tier” of the Middle East, and in its lengthy shared border with China; yet having pushed out so many Russian divisions and air squadrons to stabilize those frontiers has not produced the hoped-for invulnerability. Pulling back from eastern Europe or making border concessions to China is also feared, however, not only because of the local consequences but because it may be seen as an indication of Moscow’s loss of willpower. And at the same time as the Kremlin wrestles with these traditional problems of ensuring

territorial

security for the country’s extensive landward border, it must also try to keep up with the United States in rocketry, satellite-based weapons, space exploration, and so on. Thus, the USSR—or, better, the Marxist system of the USSR—is being tested

both quantitatively and qualitatively in the world power stakes; and it does not like the odds.

But those odds (or “correlation of forces”) would obviously be better if the economy were healthier, which brings us back to Russia’s long-term problem. Economics matters to the Soviet military, not merely because they are Marxist, and not only because it pays for their weapons and wages, but also because they understand its importance for the outcome of a lengthy, Great Power, coalition war. It

might

be true, the

Soviet Military Encyclopedia

conceded in 1979, that a global coalition war would be short, especially if nuclear weapons were used. “However, taking into account the great military and economic potentials of possible coalitions of belligerent states, it is not excluded that it might be protracted also.”

204

But if such a war is “protracted,” the emphasis will again be upon economic staying power, as it was in the great coalition wars of the past. With that assumption in mind, it cannot be comforting to the Soviet leadership to reflect that the USSR possesses only 12 or 13 percent of the world’s GNP (or about 17 percent, if one dares to include the Warsaw Pact satellites as

plus

factors); and that it is not only far behind both the United States and western Europe in the size of its GNP, but it is also being overtaken by Japan and may—if long-term growth rates continue as they are—even find itself being approached by China in the next thirty years. If that seems an extraordinary claim, it is worth recalling the cold observation by

The Economist

that in 1913 “Imperial Russia had a real product per man-hour 3

Vi

times greater than Japan’s [but it] has spent its nigh 70 socialist years slipping relatively backwards, to maybe a quarter of Japan’s rate now.”

205

However one assesses the military strength of the USSR at the moment, therefore, the prospect of its being only the fourth or fifth among the great productive centers of the world by the early twenty-first century cannot but worry the Soviet leadership, simply because of the implications for long-term Russian power.

This does

not

mean that the USSR is close to collapse, any more than it should be viewed as a country of almost supernatural strength. It

does

mean that it is facing awkward choices. As one Russian expert has expressed it, “The policy of guns, butter, and growth—the political cornerstone of the Brezhnev era—is no longer possible … even under the more optimistic scenarios … the Soviet Union will face an economic crunch far more severe than anything it encountered in the 1960s and 1970s.”

206

It is to be expected that the efforts and exhortations to improve the Russian economy will intensify. But since it is highly unlikely that even an energetic regime in Moscow would either abandon “scientific socialism” in order to boost the economy or drastically cut the burdens of defense expenditures and thereby affect the military core of the Soviet state, the prospects of an escape from the contradictions which the USSR faces are not good. Without its massive

military power, it counts for little in the world;

with

its massive military power, it makes others feel insecure and hurts its own economic prospects. It is a grim dilemma.

207

This can hardly be an unalloyed pleasure for the West, however, since there is nothing in the character or tradition of the Russian state to suggest that it could ever accept imperial decline gracefully. Indeed, historically,

none

of the overextended, multinational empires which have been dealt with in this survey—the Ottoman, the Spanish, the Napoleonic, the British—ever retreated to their own ethnic base until they had been defeated in a Great Power war, or (as with Britain after 1945) were so weakened by war that an imperial withdrawal was politically unavoidable. Those who rejoice at the present-day difficulties of the Soviet Union and who look forward to the collapse of that empire might wish to recall that such transformations normally occur at very great cost, and not always in a predictable fashion.

It is worth bearing in mind the Soviet Union’s difficulties when one turns to analyze the present and the future circumstances of the United States, because of two important distinctions. The first is that while it can be argued that the American share of world power has been declining

relatively

faster than Russia’s over the past few decades, its problems are probably nowhere near as great as those of its Soviet rival. Moreover, its

absolute

strength (especially in industrial and technological fields) is still much larger than that of the USSR. The second is that the very unstructured, laissez-faire nature of American society (while not without its weaknesses) probably gives it a better chance of readjusting to changing circumstances than a rigid and

dirigiste

power would have. But that in turn depends upon the existence of a national leadership which can understand the larger processes at work in the world today, and is aware of both the strong and the weak points of the U.S. position as it seeks to adjust to the changing global environment.

Although the United States is at present still in a class of its own economically and perhaps even militarily, it cannot avoid confronting the two great tests which challenge the

longevity

of every major power that occupies the “number one” position in world affairs: whether, in the military/strategical realm, it can preserve a reasonable balance between the nation’s perceived defense requirements and the means it possesses to maintain those commitments; and whether, as an intimately related point, it can preserve the technological and economic bases of its power from relative erosion in the face of the ever-shifting

patterns of global production. This test of American abilities will be the greater because it, like Imperial Spain around 1600 or the British Empire around 1900, is the inheritor of a vast array of strategical commitments which had been made decades earlier, when the nation’s political, economic, and military capacity to influence world affairs seemed so much more assured. In consequence, the United States now runs the risk, so familiar to historians of the rise and fall of previous Great Powers, of what might roughly be called “imperial overstretch”: that is to say, decision-makers in Washington must face the awkward and enduring fact that the sum total of the United States’ global interests and obligations is nowadays far larger than the country’s power to defend them all simultaneously.