The Road to Ubar (3 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clapp

I really admired Stephens. Imagine a New York lawyer in failing health who was advised by his physician to seek a cure in travel and restâand chose to venture across the Sinai and the deserts beyond, where no American had ever set foot. Certainly the desert Arabs had a weakness for brigandage, Stephens noted, but also they valued poetry, and they had a streak of chivalry that, if need be, dictated sharing their waterskin with their worst enemy. They believed that all others, like themselves, were guests of God in the wilderness and should not be denied God's gifts of sustenance and shelter.

What comes across in this and other accounts is that the Arabs of the desert were perhaps excitable and hot-tempered yet, surprisingly, not that intolerant of adherents of Western religions. They may have been riled more by deception than by infidelity. Englishman Gifford Palgrave journeyed deep into Arabia, freely admitting that he was a simple "Jewish Jesuit."

3

And his countryman Charles Doughty persistently chided his Arab hosts for their lack of Christian charity (which they confirmed by throwing him in jail with predictable regularity). Even so, they allowed him to travel back and forth along the northern reaches of the Rub' al-Khali.

Anxious to obtain a copy of Doughty's masterpiece,

Travels in Arabia Deserta

(1868), I stopped by Hyman and Sons bookshop on a Saturday morning. A bell tinkled as I stepped inside, and I found myself the sole customer amid a jumble of books shelved, stacked on the floor, piled on tables. One table had been cleared off and was set with a pitcher of milk, glasses, and a plate of cookies. The door to a back room swung open.

"Go ahead. Somebody's got to eat them." It was Virginia. Though I never saw anything of Hyman, much less his Sons, I had gotten to know and respect Dr. Virginia Blackburn, who was clearly in charge here. She was in her late sixties, and if there was a word to describe her it was "formidable." "Gruff" also comes to mind.

"Charles Doughty," I inquired. "

Travels in Arabia Deserta.

Have it by any chance?"

"No," said Virginia.

"Well, then, maybe..." I started to say, wondering if the book could be tracked down.

"No," repeated Virginia, peering over her steel spectacles. "You wouldn't like it. Not at all." Then, hesitating not a second, she rounded the counter, marched across the shop, ran her finger across a shelf, and removed a modest worn blue volume. "Read this."

"Well, no, what I really..."

"Blowhard. Full of himself, I'll tell you," Virginia proclaimed, coming down pretty hard on poor Doughty. "Tried to reinvent the English language, making it courtly like classical Arabic." By way of contrast she held out the blue volume. On its cover was a lone, faded golden figure riding a camel and the title

Arabia Felix.

"Read this."

"Well, well I'm not sure ... but okay." Having sampled the cookies, it seemed impolite to leave empty-handed.

"Good. You'll like it. He had red hair, like you," she said, referring to the author of the book, Bertram Thomas.

Bertram Thomas, I soon learned, was an amazing, tenacious, extremely likable fellow. But for his refreshing lack of self-promotion, he would be counted among the greatest of Arabian explorers. He writes nothing of his life prior to the day in the late 1920s that he set foot in Arabia Felix ("Happy Arabia," the old Roman name for southern Arabia), where he had accepted an offer to become the wazir, or financial adviser, to the sultan of Muscat and Oman. It was hardship duty. For the better part of the year, the small coastal city of Muscat baked and sweltered like no other place on earth. Nighttime temperatures refused to drop, as they did inland in the desert. At two o'clock in the morning, the temperature was as high as 124 degrees Fahrenheit, the humidity an unbearable 100 percent.

Thomas's Muscat days were spent managing, as best he could, the accounts of a court and country that exported only firewood, rotting sardines (for fertilizer), and slaves. Every day at sunset, a cannon was fired, and the gates of the walled medieval city swung shut. Until dawn the next day, everyone was confined to their dwellings, with the exception of the chosen few to whom the sultan had issued a special identifying lantern.

As wazir, Thomas had a lantern, and at night he could roam the fitfully sleeping city. He could climb its medieval mud-brick walls and gaze away to the north. Beyond the coastal mountains, he knew, the moon that shone on Muscat shone also on the dunes of the Rub' al-Khali. The desert was the secret reason Thomas had come here: he had long wanted to be the first Westerner not only to venture into its heart but to actually cross itâeven though T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) had determined that "nothing but an airship can do it."

4

In his time in Muscat, Bertram Thomas changed. A photograph taken early on shows him posed in front of a crumbling doorway, incongruously dressed in a wool suit and felt hat. But soon the hat was replaced by a jaunty turban, the somber suit by a flowing robe. He raised a beard and carried a camel stick. And Thomas found excuses to venture away from Muscat. On his travels he got along famously with desert tribesmen. In their company he rode by camel to the edge of the Rub' al-Khali and saw for himself that (as a bedouin saying went), "Where there is no water, that's the Empty Quarter; no man goes thither."

Back at the sultan's court, Thomas was asked a question:

"Why aren't you married, O Wazir?" was fired off at me by an uncomprehending Arab.

I expatiated on the difficulties under which a Christian labored, especially one serving in the East, and pointed to the comforting doctrine that for a man it was never too late.

"Ah!" said the Sultan, knowing of my secretly cherished desire, "quite right.

Insha'allah,

I will help to marry you one of these days to that which is near to your heartâ

Rub' al-Khali. Insha'allah!

""A virgin indeed," quoth Khan Bahadur, his private secretary.

"

Amin!

" I muttered to myself. "So may it be."

5

But to Bertram Thomas's increasing dismay, the sultan was reluctant to let his wazir go roaming north across the great desert. And a rival now threatened Thomas's dream. In Riyadh, in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Harry St. John Philby, a flamboyant Arabist late of the British Foreign Service, was poised to attempt a crossing of the Rub' al-Khali in the opposite direction, north to south.

6

The two men knew each other. Earlier in the decade, Thomas had spent some time working for the British Foreign Service in Transjordan. Harry Philby had been his superior and had advised Thomas to take the Muscat and Oman assignment, confiding that Muscat was "the best starting point for crossing the Empty Quarter." There's a hint of duplicity here. Did Philby make the suggestion out of the goodness of his heart? Or did he see this as an opportunity to get Thomas out of the way, to put him in the clutches of a possessive and paranoid sultan, so that he, Philby, could claim exploration's last great prize?

The rivalry was heightened by a strange shared vision. Both Thomas and Philby saw the Rub' al-Khali as a beckoning yet veiled virgin. Thomas called the Rub' al-Khali "the sands of my desire." Philby called the same sands "the bride of my constant desire."

7

But, though there were two suitors, there could be only one husband.

On an October night in 1930, unbeknownst to his sultan, Bertram Thomas stole away from Muscat with the anticipation that "tomorrow, the news of my disappearance would startle the bazaar and a variety of fates would doubtless be invented for me by imaginations of oriental fertility."

8

He rowed to a rendezvous with a passing oil tanker and "ere four bells had struck" was on his way by sea to the southern Omani town of Salalah. There he would find guides and outfit his expedition.

Thomas liked Salalah. The place had a cheerful African air. He was particularly amused by the unusual fate of the town's black slaves. Their Arab masters led grim, obsessive lives, forever worrying over the shame that would fall upon them if any of their veiled, sequestered wives or daughters took a wayward turn. By contrast, a household's slaves enjoyed a happy-go-lucky freedom unimaginable to their masters. And, dancing and singing in the dirt streets of Salalah, they saw Thomas off on December 10, 1930, as he headed north with a train of fifteen camels and a rascally band of bedouin of uncertain repute. Salalah's

wali,

or mayor, had warned Thomas, "If there is a thing they do better than lying, it is stealing."

Far to the north, in Riyadh, Harry Philby was informed that this year, at least, he would not be granted permission to travel south across the Rub' al-Khali. If he would like, the following year he could again petition the king, 'Abdul 'Aziz ibn Sa'ud.

Crossing the Dhofar Mountains, which abruptly rise beyond Salalah, Thomas displayed a fine eye for geographic and ethnographic detail. In

Arabia Felix

he noted that the mountain tribesmen spoke a strange, non-Arabic language and considered themselves descendants of a mythical race known as "the People of'Ad." He witnessed blood sacrifice and an exorcism performed with frankincense and fire. All the while, he charted his progress with an accuracy that is amazing considering that he had to make his navigational sightings in secret, "lest I be suspected of magic or worse."

9

Beyond the mountains lay a "barren plain, sun-baked and filmy with mirages," desolate but for occasional sightings of Arabian oryxes, running wild and free. Five waterless days took Thomas to the remote waterhole of Shisur, the site of an abandoned "rude fort," a last, forlorn trace of civilization. A day beyond Shisur, Thomas sighted "the sands of my desire." But his little band did not immediately plunge into the Rub' al-Khali. They skirted its southern edge, on the lookout for the first of a series of wells they hoped would see them safely across the dunes.

The seventh waterless day out of Shisur began like the others. Thomas wrote:

Our morning start was sluggish. We straggled because of the cold and the hunger and the many transverse sand ridges, and straggling camels mean a slow caravan. An hour's march brought us to a wide depression....

Suddenly the Arabs, who were always childishly anxious to draw attention to anything they thought would interest me, pointed to the ground. "Look, Sahib," they cried. "There is the road to Ubar."

"Ubar?" I wondered.

"It was a great city, our fathers have told us, that existed of old; a city rich in treasure, with date gardens and a fort of red silver. (Gold?) It now lies buried beneath the sands in the Ramlat Shu'ait, some few days to the north."

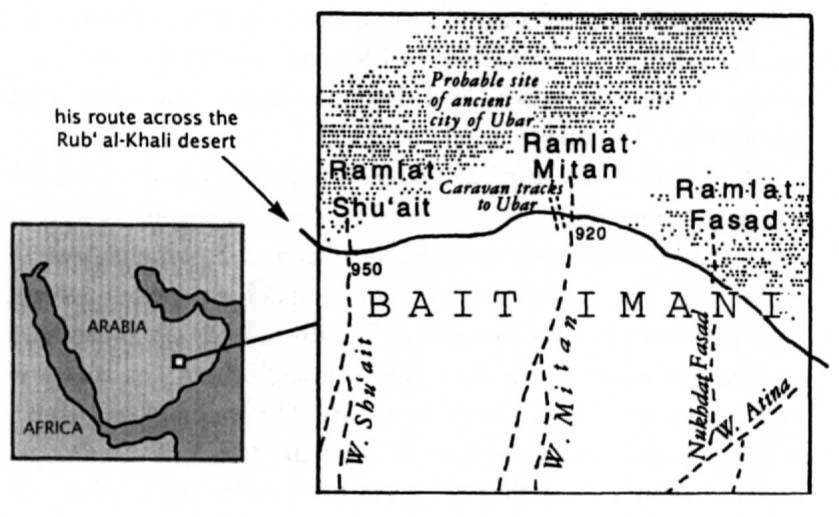

Other Arabs on my previous journeys had told me of Ubar, the Atlantis of the sands, but none could say where it lay. All thought of it had been banished from my mind when my companions cried their news and pointed to the well-worn tracks, about a hundred yards in cross section, graven in the plain. They bore 325°, approximately lat. 18°45'N., long. 52°30'E. on the verge of the sands.

10

On his remarkably accurate map of Arabia, prepared for the Royal Geographic Society, that is where Bertram Thomas noted "the road to Ubar."

It was an unexpected, exciting discovery, and Thomas must have been tempted to follow the impressive road to the fabled city. But a side trip at this point would have depleted his waterskins and jeopardized his dream of reaching the desert's far side. Passing the road to Ubar by, Thomas embraced the Rub' al-Khali, whose virgin landscape he found less an enchanting bride and more "a hungry void and an abode of death." Great was his relief when, ninety-five days after leaving Salalah and the Arabian Sea, he came in sight of the town of Doha and the Persian Gulf. He'd done it! The Rub' al-Khali was his.

Detail of Bertram Thomas's map of Arabia

In Riyadh, the news so enraged and disheartened Harry Philby that his route across the Rub' al-Khali desert he shut himself indoors and refused to come out for a week. When he did, he made no effort to conceal his feeling that he had been betrayed by his friend and protégé. Quoting a verse of Arabic poetry, he expressed his hurt: "Twas I that learn'd him in the archer's art; / At me, his hand grown strong, he launched his dart."

11

Philby's petulance aside, Thomas's achievement was greeted with acclaim. T. E. Lawrence called it "the finest thing in Arabian exploration." He wrote, "Bertram Thomas has just crossed the Empty Quarter, that great desert of southern Arabia. It remained the only unknown quarter of the world, and it is the end of the history of exploration."

12

Or was it? Thomas had crossed the desert but had by no means thoroughly explored it. His very journey had a tantalizing loose end: a mysterious byway, a road leading to a lost city of the sands. Granted that his knowledge of Ubar came from his not-known-for-their-truthfulness bedouin companions. ("If there's anything they do better than lying, it's stealing.") Still, there was the fact of the road itself, witnessed by a keen observer, a man not to be doubted. And all roads lead somewhere.