The Road to Ubar (6 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clapp

The inhabitants of that place said that there are wild men and evil beasts there ... There were men each twenty-four cubits tall; and they had long necks, and their hands and fingers were like saws...

Moving on we came to a place where there were headless men. They had no heads at all, but had their eyes and their mouths on their chests, and they talked with their tongues like men ... Then there appeared to us, about nine or ten o'clock, a man as hairy as a goat. I thought of capturing the man for he was ferociously and brazenly barking at us. And I ordered a woman to undress and go to him on the chance that he might be vanquished by lust. But he took the woman and went far away where, in fact, he ate her.

6

In their bizarre way, the Alexander books were instructive, for here was a good take on how myth worked. In the past I had read of myth as "hieratic" or "teleodidactic," cryptic cultural constructs that I could never quite grasp. Here myth was anything but arcane; it was a lively, mischievous animal with scissor hands, barking at us, that delighted in pouncing on the truth and making a merry hash of it. Yet shards of truth survive. There

was

an Alexander, and he did have great adventures. The Alexander books were reasonably accurate in their depiction of

some

peoples, places, and events.

I understood, too, why myths persist across the centuries. They offer entertainment. They have an action-adventure quotient, they have an aura of wonder and mysteryâand, best yet, they offer insights into the glories and fallibilities of the human heart, and how and why we live and die. As the conquest-obsessed, immortality-seeking Macedonian Alexander reaches the far side of his desert, two birds with human faces fly overhead and, in Greek, ask, "Why do you tread this earth looking for the home of the gods? For you are not able to set foot in the Blessed Island of the skies. Why do you struggle to rise to heaven, which is not within your power?"

7

These were sensible birds, not about to buy into Alexander's proclamation in 329

B.C.

that he was a god. For all his might, chirped the duo, the Macedonian could not transcend his mortality.

Following the mythical footsteps of Alexander led me from the University Research Library to the gates of the Huntington Library in San Marino, near Pasadena, where I was kindly (and capriciously?) accepted as a "Reader," a researcher with formal privileges.

Set in magnificent grounds, the Huntington is a great marble building guarded by solemn Greek gods and housing a major research library of some 2 million books and 6 million manuscripts. Though famed for its holdings on British history and literature, the Huntington proved to have a surprising amount of material on Arabia: rare and wonderful editions of

The Arabian Nights,

the entire personal library of the great explorer-linguist-historian Sir Richard Burton, and, of special interest, a collection of original editions and manuscripts of the maps of Claudius Ptolemy.

In the late 1400s European printing houses sought to outdo each other bringing out woodcut editions of Ptolemy's atlas of the known world. Bologna, 1477 ... Rome, 1478 ... Ulm, 1482 ... These

Cosmographias,

as they were called, were impressive. The editions at the Huntington were leather-bound and hand-colored, often in gold. Each turn of their vellum pages gave a whiff of the past, musty and mysterious. Locating "Tabla Sexta Asiae"âPtolemy's map of ArabiaâI saw that hundreds of sites and geographic features were accurately identified.

Yet understanding Ptolemy's

Cosmographias

was not a simple matter. It took me a while to grasp when and how they were compiled and what exactly they portrayed. To begin with, the

Cosmographias

were not at all what they first seemed. Though compiled in the 1400s, they were

not

the product of the Renaissance quest for knowledge and new horizons. Ptolemy was born in Greece and lived in Egypt circa 110â170

A.D.

The Renaissance editions were, in substance,

reissues

of maps produced some thirteen hundred years earlier at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, the Great Library of Alexandria.

Sometime around 150

A.D.,

as overseer of the Great Library, Claudius Ptolemy set out to map the known world. For information, he drew on his library's estimated 750,000 manuscripts, among them a number of "Peripluses" (literally, "round trips"), records of coastlines compiled by seafaring Greek traders. In the case of Arabia, these traders also brought back accounts of inland sites gathered, not firsthand but from local tribesmen. These informants measured camel journeys from place to place in "stages," each equaling a day's ride. Calculating that a stage averaged thirty to thirty-five miles, Ptolemy did his best to estimate the whereabouts of inland cities and towns.

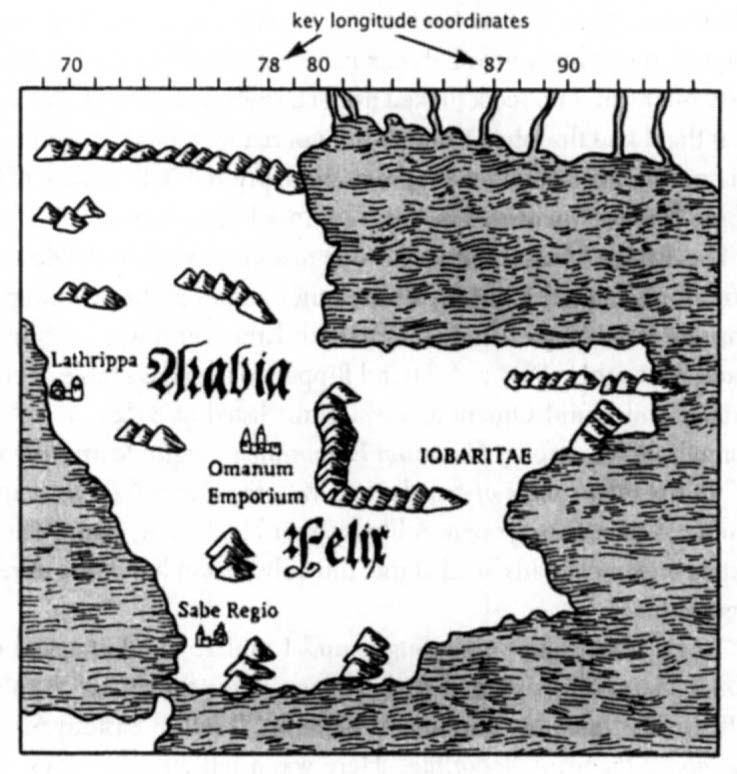

To plot this and his other accumulated data, Ptolemy not only envisioned the world as round, but invented and set upon it lines of longitude and latitude. Every site was then given identifying coordinates. In Arabia, for instance, Medina (then called Yathrib, or Lathrippa) was at 71° à 23°, and Saba Regio, the royal city of Sheba, was at 73° à 16°.

8

In its original form, Ptolemy's atlasâincluding his map of Arabiaâwas a wonder of the world. Nothing so complete, so detailed, so accurate, had been done before. And therefore it was a very sad day when, in 391

A.D.

, at the order of the Roman emperor Theodosius I, a religious mob trashed and torched Alexandria's libraryâand Ptolemy's atlas went up in smoke.

Nonetheless, fragments of Ptolemy's work survived. At least one copy of his table of coordinatesâhis listings of landmarks and sitesâwas saved and passed down through the centuries, until in the late 1400s European mapmakers laid out longitude and latitude grids and plotted afresh Ptolemy's coordinates of coastlines, mountains, rivers, and tribal fiefdoms. They marked his cities and towns with quaint castles or little dots, often in gold. They reconstructed, quite successfully, the world as Ptolemy knew it, as it was not long after the time of Christ.

On Ptolemy's map of Arabiaâif anywhereâI should find Ubar. And sure enough, on most editions, the tribal name "Iobaritae"âLatin for "Ubarites"âappears more or less where Bertram Thomas encountered his road to Ubar. But there was no identifiable

settlement,

only evidence that an Ubarite tribe once may have wandered the region's sandy wastes. No castle or golden dot on Ptolemy's map, no city. And it wasn't as if I could look further into the past. Before Ptolemy, the only maps were very crude and usually local.

For several weeks there seemed no way to get beyond this impasse. Then, to better understand how Ptolemaic maps were constructedâ and to attempt to conjure something out of nothingâI decided to make one of my own, step by step. Working from a table of coordinates printed in Ulm, Germany, in 1482, I plotted nearly four hundred landmarks and towns, just as Renaissance mapmakers had done. The project, which took several evenings, was intriguing, much like working a jigsaw puzzle. But there were no surprises. Except ... a day or two after I'd finished, one of the places I'd plotted popped up in my mind and bothered me. Omanum Emporium, "the marketplace of Oman," appeared in

western

Arabia at 77° à 19°. As far as I knew, the ancient land of Oman was in

eastern

Arabia (as today's Sultanate of Oman is).

Ptolemy's map of Arabia (simplified)

What, then, was "the marketplace of Oman" doing so far from home? The next time I could make it over to the Huntington, I doggedly double-checked the library's many editions and manuscripts of Ptolemy's

Cosmographia.

Nothing to be learned. When I returned the atlases to the rare book desk, I felt a little guiltier than usual for asking the librarians to lug these enormous volumes back and forth from the Huntington's vaults. It was a little before five, closing time. I hesitated, then drifted back to the library's main reading room. Though the lights were off, its oak paneling glowed in the last rays of the winter sun. I noticed, tucked under a shelf, a version of Ptolemy's atlas that I had thumbed through but not really studied. It was not an original edition but rather a reproduction, printed in the 1930s, of the Ebner Manuscript owned by the New York Public Library.

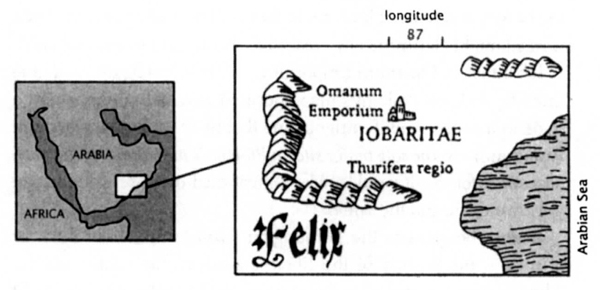

The Ebner Manuscript was a one-of-a-kind work, hand-done in 1460. It predated, I realized, all the other atlases at the Huntington. I turned to its map of Arabia. Omanum Emporium was in its usual place, at roughly 78° à 20°. Then I flipped to the atlas's table of coordinates and found Omanum Emporium listed at 87°40' à 19°75'. Something was wrong.

Omanum Emporium's longitude was listed as 87° in the atlas's table of coordinates, yet placed at

78°

on its map of Arabia. A

door swung open. A library guard looked in, glanced at his watch, and cocked his head at me, the only person left in the cavernous room.

"Just a second, just wrapping it up," I said ... and checked the Ebner Manuscript's map of Arabia to see where the 87°40' à 19°75 listed in the table of coordinates might be. It fell in eastern Arabia,

just above the word "lobaritae.

" Here was a settlementâlong misplacedâin the homeland of the Ubarites! And it was a major settlement, for in some editions of Ptolemy's map of Arabia, a dozen or so cities are singled out (sometimes by larger type, sometimes by an asterisk) as being particularly important. Omanum Emporium consistently makes the cut.

What exactly happened in the monastery of Ebner in the 1460s is not clear. But a likely scenario is this: the creator of the manuscript correctly copied an earlier list of Ptolemy's coordinates and, working from these coordinates, set to drawing his map of Arabia. He outlined the coast, added mountains and rivers. One by one, he filled in the cities and towns. When he got to Omanum Emporium he ran out of ink ... or it was time to light a candle ... or perhaps he paused to brush away the scriptorium cat. One way or another, the scribe slipped up. When he put pen to parchment, the 87° latitude of the table of coordinates became 78° on the map. This simple inversion placed Omanum Emporium far west of where it belonged, a mistake that appears to have been repeated on later maps copied in Bologna, Rome, and Ulm.

Detail of Ptolemy's map of Arabia (corrected)

Heading home that afternoon, I was barely aware of what freeway I was driving. Was "Omanum Emporium" Ubar itself? In the ancient world, sites frequently had several names, just as they have in modern history. What was once Niew Amsterdam is Manhattan, Gotham, the Big Apple. Yet Omanum Emporium did not rest easily at its new location. What was a "market town of Oman" doing way out in the desert? An emporium was typically a seaside trading town.

Back at the Huntington, I found the answer no more than a half inch away on Ptolemy's map. Close by Omanum Emporium's newly established site was the legend

Thurifero Regio,

or Incense Land. In the ancient world incense was a major commodity, in demand for both temple and household use. Frankincense, I had read, was the resin of a humble desert tree, which, by the time it reached the faraway markets of the Mediterranean, was as valued as gold.

Omanum EmporiumâUbarâcould well have had a role in the harvest and trade of incense. In fact, understanding how the trade worked might clarify the city's reason for being, and its rise and fall.

Iobaritae ... Omanum Emporium ... Thurifero Regio ... These three legends on Ptolemy's map appeared to equal a tribe, a city, a trade in incense. And it intrigued me that in all of Arabia, Omanum Emporium was

the sole major site on Ptolemy's map that has not been accounted for.

So it would make a great deal of sense if it and lost Ubar were one and the same.

Before the gates to the Huntington swung shut, I had time for a walk in my favorite of the library's gardens, the cactus garden. Though it was winter, pencil and silver cholla cactus were in bright yellow and red bloom. Admiring them, I reflected on my journey across the deserts of many maps of Arabia, new and old. With no little difficulty, I had made it past the saw-fingered man and the barking goat-man and had stood in awe of the landmark achievement of Claudius Ptolemy, the world's first great cartographer.