The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood (2 page)

Read The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood Online

Authors: David R. Montgomery

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Religious Studies, #Geology, #Science, #21st Century, #Religion, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail

I found reading the historic works of theologians, natural philosophers, and scientists a fascinating experience, one that left me with an appreciation for the rich and engaging interplay between biblical interpretation and the development of geology. Noah’s story is central to one of the longest-running debates between science and religion as people sought, and still seek, to reconcile scriptural interpretation with observations of the natural world. We mortals have long been struggling to understand who we are, and probably always will. Even today, interpretations of the biblical flood story remain central to understanding modern culture wars—no matter how one views them—because how we read ancient stories still defines the way we see the world, and thus ourselves.

1

Buddha’s Dam

A

S A GEOLOGIST

, I’ve had plenty of surprises in the field, but I never expected that an excursion to a remote corner of Tibet would lead me to a new appreciation for the biblical story of Noah’s Flood. My specialty is geomorphology, the study of processes that create and shape topography. Over the last several decades I’ve explored how landscapes evolve—where stream channels begin, how landslides sculpt hillslopes, and why rivers carve deep gorges through mountain ranges.

In the spring of 2002 I joined a research expedition to the Tsangpo River in southeastern Tibet. The team needed a geomorphologist with river experience to study how the Tsangpo had sawed down through kilometers of rock to carve the world’s deepest gorge. I couldn’t turn down the chance to visit the roof of the world.

As we drove down from the pass toward the Tsangpo on the newly paved road southeast of Lhasa, I noticed flat-topped piles of sediment rising above the valley floor. Known as topographic terraces, these elevated islands of flat ground can form in different ways, most commonly when an incising river abandons an old riverbed. I watched for clues to determine what created these.

Photograph of a topographic terrace, the top of which corresponds to the level of an ancient lake that once filled the valley of the Tsangpo River, Tibet

(

photograph by the author

).

Over the course of our several-week expedition I collected the pieces of a landscape-scale puzzle. Flat-topped piles of loose sediment—gravel, sand, and silt—stuck up hundreds of feet into the air where tributary valleys entered the main valley. More terraces lay at about the same elevation at each confluence where smaller streams joined the river. From our hotel near the foot of the valley wall we could see a terrace rising above the edge of town a few blocks away. A short hike up a dirt road cut up through the side of the terrace revealed hundreds of alternating layers of silt and finer clay. Segregation into distinct layers sorted by size meant that these sediments were laid down in quiet water. Such fine material would not have settled out in a turbulent river. The implication was clear. An ancient lake once filled the valley.

Sketching the extent of the flat terrace surfaces onto our map as we drove along the valley, I badgered my compatriots into occasionally stopping for a closer look at these curious piles of sediment laid out like a giant’s playground. Some were dried-up gravel riverbeds perched well above the modern river. Others were lake terraces made of layered silt and clay. How did they get there?

A coherent picture began to emerge as we traversed up and down the valley. The terraces made of river gravel continued down the valley bottom to an elevation corresponding to the top of the lake sediments, defining the ancient shoreline where the rivers had entered the lake. In addition to prominent terraces that rose a few hundred feet above the modern river, the remnants of a second set of higher terraces preserved at a few remote locations halfway up the valley walls attested to an even deeper lake. At least twice in the recent geologic past a lake extended hundreds of kilometers upstream from the Tsangpo Gorge. I was onto something.

It was thrilling to have scientific sleuthing that started as little more than a hunch lead to a solid story. Once I saw the pieces and knew how they fit together, the story of ancient lakes that once filled the valley of the Tsangpo stood out plain as day in the form of the land.

What do you see when you look at the land? Something stable and reassuringly solid. A slope to ski down? A surface to pave over? Geologists see the world as incredibly dynamic and ever-changing—only change occurs slowly over immense spans of time.

I’ve learned to see what the land used to look like, and what it might look like in the future. Reading a landscape is an ongoing process of combining curiosity and inquiry. Why is that hillside bare and rocky? Why is that one covered with soil? Deciphering topography makes geologists natural storytellers. We piece together fragmentary clues in rocks and landforms to connect dots across landscapes, mountain ranges, and continents and tell stories with whole chapters lost to erosion and time. And here in the valley of the Tsangpo was a great story, except for one big loose end.

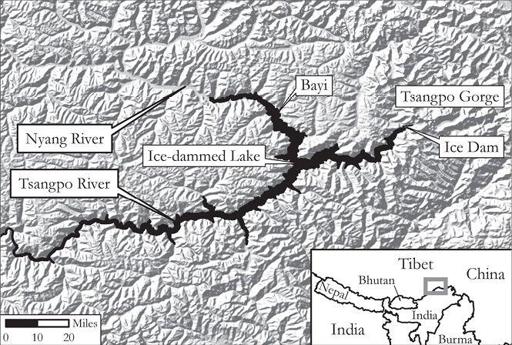

Map of the Tsangpo River, Tibet, showing the Nyang River, the town of Bayi (where our hotel was located), and the moraine dam at head of Tsangpo Gorge. The reconstructed extent of the lower paleo-lake is shown in black.

Looking at the map, there was no obvious dam to hold back our newly discovered ancient lakes. What kept them from draining down into the Tsangpo Gorge? Many miles downstream, right at the head of the gorge, we discovered glacial debris plastered on both sides of the valley confirming that a massive tongue of ice had once plunged down the 25,000-foot-high peak of Namche Barwa and blocked the river. The two levels of terraces extending far upstream indicated that a wall of ice and mud dammed the river, not just once but time and again, backing up a great lake that filled the valley.

As you might imagine, ice doesn’t make a very good dam. Once the lake filled enough to float or breach the dam, a rush of liberated water roared down the gorge, scouring out everything in its path. Upstream of the gorge, we found horizontal stripes of silt plastered onto the valley walls. Here were old shorelines confirming that the ice advanced to block the river over and over again, most likely during cold glacial periods or at times when strong monsoons delivered extra snow to the glacier’s source on the high peak. As the glacier repeatedly dammed the throat of the gorge, ice-dam failures generated catastrophic floods that drained ancient lakes impounded in the valley upstream.

One day as we drove down the valley toward the gorge, one of my graduate students relayed information from a guidebook he’d brought along. Local folklore told of a traditional kora—a Buddhist pilgrimage trek—that circled a small peak ringed by lake terraces. Pilgrims walk the kora to commemorate how Guru Rimpoche brought Buddhism to Tibet through defeating a powerful lake demon, draining its home to reveal fertile valley-bottom farmland. It was a feat impressive enough to convert the locals. I began to think that an oral tradition might record our glacial dam-break flood.

Suspicion moved beyond idle speculation when we got the radiocarbon dates from wood fragments I’d painstakingly collected from the lake terraces. Radiocarbon dating uses the ratio of carbon isotopes in once-living matter to determine how long ago it died.

1

The technique works because carbon-14 (

14

C) decays to carbon-12 (

12

C) at a known rate, and all living things start with a

14

C/

12

C ratio equal to that in the atmosphere from which the carbon was originally taken up by photosynthesis. Wood fragments from the higher terraces of the older lake were almost ten thousand years old, dating from the tail end of the last glaciation of what’s popularly known as the ice age. Fragments from the younger lake were only about twelve hundred years old—dating from around the eighth century

AD

.

This was about the time that Guru Rimpoche arrived in Tibet. Did the geologic story I read in the landforms really support a Tibetan folktale? Or was it that the folktale told the geologic story?

Two years later, in 2004, I returned to Tibet to explore the story of the lake-draining flood. On our first trip we had hired a local farming couple to collect monthly samples of river water. When I told the farmer’s wife how we’d discovered that the whole valley was once an ancient lake, she replied that yes, she knew about that. Caught off guard, I listened to her. She pointed out a steep hillside across the valley and described how three boats had been stranded there as the lake drained to reveal the farmland of the modern river bottom. She told me she’d heard the story from the Lamas at the local temple.

The temple sat right on top of a stack of ancient lake sediments, one of the terraces that rose to the elevation of the lower lake shoreline. A painted temple wall along an exterior walkway even had a striking portrayal of Guru Rimpoche above a lake floating before the distinctive peaks flanking the gorge entrance. Asked how Guru Rimpoche had drained the lake, the head Lama said he cared not

how

the great master did it. What was important was the fact that Guru Rimpoche had. Besides, he continued, the story we should be interested in was how the ocean once covered all of Tibet. He described how he had seen water-rounded rocks perched on mountainsides high above the valley. He assured us that the ocean once covered the high peaks. His story of a flood that submerged the world sounded familiar.

Photograph of the truncated glacial moraine where an ancient ice dam extended down off the flanks of Namche Barwa (the high peak in the background at right) to dam the Tsangpo River immediately upstream of the Tsangpo Gorge

(

photograph courtesy of Bernard Hallet

).

People around the world tell stories to explain distinctive landforms and geological phenomena. The global distribution of folklore associated with topography and great floods makes me suspect that people are hard-wired to be fascinated by and to question the origin of landscapes. I know I am. I think I was a geomorphologist before I knew what one was.