The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane (50 page)

Read The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane Online

Authors: Robert E. Howard,Gary Gianni

The Englishman was presently aware that a lean, gray-bearded Arab was walking along at his side. This Arab seemed desirous of speaking but strangely timid, and the source of his timidity seemed, curiously enough, the ju-ju stave which he had taken from the black man who had picked it up, and which he now turned uncertainly in his hands.

“I am Yussef the Hadji,” said this Arab suddenly. “I have naught against you. I had no hand in attacking you and would be your friend if you would let me. Tell me, Frank, whence comes this staff and how comes it into your hands?”

Kane's first inclination was to consign his questioner to the infernal regions, but a certain sincerity of manner in the old man made him change his mind and he answered: “It was given me by my blood-brother – a black magician of the Slave Coast, named N'Longa.”

The old Arab nodded and muttered in his beard and presently sent a black running forward to bid Hassim return. The tall sheikh presently came striding back along the slow-moving column, with a clank and jingle of daggers and sabers, with Kane's dirk and pistols thrust into his wide sash.

“Look, Hassim,” the old Arab thrust forward the stave, “you cast it away without knowing what you did!”

“And what of it?” growled the sheikh. “I see naught but a staff – sharp-pointed and with the head of a cat on the other end – a staff with strange infidel carvings upon it.”

The older man shook it at him in excitement: “This staff is older than the world! It holds mighty magic! I have read of it in the old iron-bound books and Mohammed – on whom peace! – himself hath spoken of it by allegory and parable! See the cat-head upon it? It is the head of a goddess of ancient Egypt! Ages ago, before Mohammed taught, before Jerusalem was, the priests of Bast bore this rod before the bowing, chanting worshippers! With it Musa did wonders before Pharaoh and when the Yahudi fled from Egypt they bore it with them. And for centuries it was the scepter of Israel and Judah and with it Sulieman ben Daoud drove forth the conjurers and magicians and prisoned the efreets and the evil genii! Look! Again in the hands of a Sulieman we find the ancient rod!”

Old Yussef had worked himself into a pitch of almost fanatic fervor but Hassim merely shrugged his shoulders.

“It did not save the Jews from bondage nor this Sulieman from our captivity,” said he; “so I value it not as much as I esteem the long thin blade with which he loosed the souls of three of my best swordsmen.”

Yussef shook his head. “Your mockery will bring you to no good end, Hassim. Some day you will meet a power that will not divide before your sword or fall to your bullets. I will keep the staff, and I warn you – abuse not the Frank. He has borne the holy and terrible staff of Sulieman and Musa and the Pharaohs, and who knows what magic he has drawn therefrom? For it is older than the world and has known the terrible hands of strange, dark pre-Adamite priests in the silent cities beneath the seas, and has drawn from an Elder World mystery and magic unguessed by humankind. There were strange kings and stranger priests when the dawns were young, and evil was, even in their day. And with this staff they fought the evil which was ancient when their strange world was young, so many millions of years ago that a man would shudder to count them.”

Hassim answered impatiently and strode away with old Yussef following him persistently and chattering away in a querulous tone. Kane shrugged his mighty shoulders. With what he knew of the strange powers of that strange staff, he was not one to question the old man's assertions, fantastic as they seemed. This much he knew – that it was made of a wood that existed nowhere on earth today. It needed but the proof of sight and touch to realize that its material had grown in some world apart. The exquisite workmanship of the head, of a pre-pyramidal age, and the hieroglyphics, symbols of a language that was forgotten when Rome was young – these, Kane sensed, were additions as modern to the antiquity of the staff itself, as would be English words carved on the stone monoliths of Stonehenge.

As for the cat-head – looking at it sometimes Kane had a peculiar feeling of alteration; a faint sensing that once the pommel of the staff was carved with a different design. The dust-ancient Egyptian who had carved the head of Bast had merely altered the original figure, and what that figure had been, Kane had never tried to guess. A close scrutiny of the staff always aroused a disquieting and almost dizzy suggestion of abysses of eons, unprovocative to further speculation.

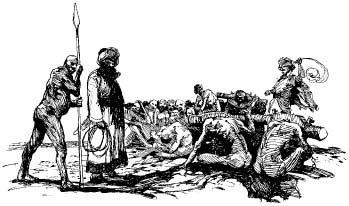

The day wore on. The sun beat down mercilessly, then screened itself in the great trees as it slanted toward the horizon. The slaves suffered fiercely for water and a continual whimpering rose from their ranks as they staggered blindly on. Some fell and half crawled, and were half dragged by their reeling yoke-mates. When all were buckling from exhaustion, the sun dipped, night rushed on, and a halt was called. Camp was pitched, guards thrown out, and the slaves were fed scantily and given enough water to keep life in them – but only just enough. Their fetters were not loosened but they were allowed to sprawl about as they might. Their fearful thirst and hunger having been somewhat eased, they bore the discomforts of their shackles with characteristic stoicism.

Kane was fed without his hands being untied and he was given all the water he wished. The patient eyes of the slaves watched him drink, silently, and he was sorely ashamed to guzzle what others suffered for; he ceased before his thirst was fully quenched. A wide clearing had been selected, on all sides of which rose gigantic trees. After the Arabs had eaten and while the black Moslems were still cooking their food, old Yussef came to Kane and began to talk about the staff again. Kane answered his questions with admirable patience, considering the hatred he bore the whole race to which the Hadji belonged, and during their conversation, Hassim came striding up and looked down in contempt. Hassim, Kane ruminated, was the very symbol of militant Islam – bold, reckless, materialistic, sparing nothing, fearing nothing, as sure of his own destiny and as contemptuous of the rights of others as the most powerful Western king.

“Are you maundering about that stick again?” he gibed. “Hadji, you grow childish in your old age.”

Yussef's beard quivered in anger. He shook the staff at his sheikh like a threat of evil.

“Your mockery little befits your rank, Hassim,” he snapped. “We are in the heart of a dark and demon-haunted land, to which long ago were banished the devils from Arabia. If this staff, which any but a fool can tell is no rod of any world we know, has existed down to our day, who knows what other things, tangible or intangible, may have existed through the ages? This very trail we follow – know you how old it is? Men followed it before the Seljuk came out of the East or the Roman came out of the West. Over this very trail, legends say, the great Sulieman came when he drove the demons westward out of Asia and prisoned them in strange prisons. And will you say –”

A wild shout interrupted him. Out of the shadows of the jungle a black came flying as if from the hounds of Doom. With arms flinging wildly, eyes rolling to display the whites and mouth wide open so that all his gleaming teeth were visible, he made an image of stark terror not soon forgotten. The Moslem horde leaped up, snatching their weapons, and Hassim swore: “That's Ali, whom I sent to scout for meat – perchance a lion –”

But no lion followed the black man who fell at Hassim's feet, mouthing gibberish, and pointing wildly back at the black jungle whence the nerve-strung watchers expected some brain-shattering horror to burst.

“He says he found a strange mausoleum back in the jungle,” said Hassim with a scowl, “but he cannot tell what frightened him. He only knows a great horror overwhelmed him and sent him flying. Ali, you are a fool and a rogue.”

He kicked the groveling black viciously, but the other Arabs drew about him in some uncertainty. The panic was spreading among the black warriors.

“They will bolt in spite of us,” muttered a bearded Arab, uneasily watching the blacks who milled together, jabbered excitedly and flung fearsome glances over the shoulders. “Hassim, 'twere better to march on a few miles. This is an evil place after all, and though 'tis likely the fool Ali was frighted by his own shadow – still –”

“Still,” jeered the sheikh, “you will all feel better when we have left it behind. Good enough; to still your fears I will move camp – but first I will have a look at this thing. Lash up the slaves; we'll swing into the jungle and pass by this mausoleum; perhaps some great king lies there. The blacks will not be afraid if we all go in a body with guns.”

So the weary slaves were whipped into wakefulness and stumbled along beneath the whips again. The black warriors went silently and nervously, reluctantly obeying Hassim's implacable will but huddling close to their white masters. The moon had risen, huge, red and sullen, and the jungle was bathed in a sinister silver glow that etched the brooding trees in black shadow. The trembling Ali pointed out the way, somewhat reassured by his savage master's presence.