The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane (55 page)

Read The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane Online

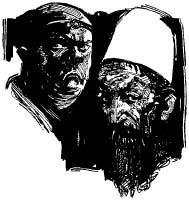

Authors: Robert E. Howard,Gary Gianni

He was dimly aware that Yamen cried out fiercely at his curses, and leaned forward in an attitude of listening. Then the powder burned out, the smoke waned away, and Kane sat groggily and bewilderedly on the throne. Yamen turned toward the king and bending low, straightened again and with his arms outstretched, spoke in a sonorous tone. The king solemnly repeated his words, and Kane saw the face of the noble prisoner go white. Then his companions seized his arms, and the band marched slowly away, their footfalls coming back eerily through the shadowy vastness.

Like silent ghosts the soldiers came from the shadows and unchained him. Again they grouped themselves about Kane and led him up and up through the shadowy galleries to his chamber, where again Shem locked his chains to the wall. Kane sat on his couch, chin on his fist, striving to find some motive in all the fantastic actions he had witnessed. And presently he realized that there was undue stir in the streets below.

He looked out the window. Great fires blazed in the market-place and the figures of men, curiously foreshortened, came and went. They seemed to be busying themselves about a figure in the center of the market-place, but they clustered about it so thickly he could make nothing of it. A circle of soldiers ringed the group; the firelight glanced on their armor. About them clamored a disorderly mob, yelling and shouting. Suddenly a scream of frightful agony cut through the din, and the shouting died away for an instant, to be renewed with more force than before. Most of the clamor sounded like protest, Kane thought, though mingled with it was the sound of jeers, taunting howls and devilish laughter. And all through the babble rang those ghastly, intolerable shrieks.

A swift pad of naked feet sounded on the tiles and the young black, Sula, rushed in and thrust his head into the window, panting with excitement. The firelight from without shone on his ebon face and white rolling eyeballs.

“The people strive with the spearmen,” he exclaimed, forgetting, in his excitement, the order not to converse with the strange captive. “Many of the people loved well the young prince Bel-lardath – oh, bwana, there was no evil in him! Why did you bid the King have him flayed alive?”

“I!” exclaimed Kane, taken aback and dumbfounded. “I said naught! I do not even know this prince! I have never seen him.”

Sula turned his head and looked full into Kane's face.

“Now I know what I have secretly thought, bwana,” he said in the Bantu tongue Kane understood. “You are no god, nor mouthpiece of a god, but a man, such as I have seen before the men of Ninn took me captive. Once before, when I was small, I saw men cast in your mold, who came with their black servants and slew our warriors with weapons which spoke with fire and thunder.”

“Truly I am but a man,” answered Kane, dazedly, “but what – I do not understand. What is it they do in yonder market-place?”

“They are skinning prince Bel-lardath alive,” answered Sula. “It has been talked freely among the market-places that the king and Yamen hated the prince, who is of the blood of Abdulai. But he had many followers among the people, especially among the Arbii, and not even the king dared sentence him to death. But when you were brought into the temple, secretly, none in the city knowing of it, Yamen said you were the mouthpiece of the gods. And he said Baal had revealed to him that prince Bel-lardath had roused the wrath of the gods. So they brought him before the oracle of the gods –”

Kane swore sickly. How incredible – how ghastly – to think that his lusty English oaths had doomed a man to a horrible death. Aye – crafty Yamen had translated his random words in his own way. And so the prince, whom Kane had never seen before, writhed beneath the skinning knives of his executioners in the market-place below, where the crowd shrieked or jeered.

“Sula,” he said, “what do these people call themselves?”

“Assyrians, bwana,” answered the black absently, staring in horrified fascination at the grisly scene below.

III

In the days that followed Sula found opportunities from time to time to talk with Kane. Little he could tell the Englishman of the origin of the men of Ninn. He only knew that they had come out of the east in the long, long ago, and had built their massive city on the plateau. Only the dim legends of his tribe spoke of them. His people lived in the rolling plains far to the south and had warred with the people of the city for untold ages. His people were called Sulas, and they were strong and war-like, he said. From time to time they made raids on the Ninnites, and occasionally the Ninnites returned the raid – in such a raid Sula was captured – but not often did they venture far from the plateau. Though of late, Sula said, they had been forced to range further afield in search of slaves, as the black people shunned the grim plateau and generation by generation moved further back into the wilderness.

The life of a slave of Ninn was hard, Sula said, and Kane believed him, seeing the marks of lash, rack and brand on the young black's body. The drifting ages had not softened the spirit of the Assyrians, nor modified their fierceness, a byword in the ancient East.

Kane wondered much at the presence of this ancient people in this unknown land, but Sula could tell him nothing. They came from the east, long, long ago – that was all Sula knew. Kane knew now why their features and language had seemed remotely familiar. Their features were the original Semitic features, now modified in the modern inhabitants of Mesopotamia, and many of their words had an unmistakable likeness to certain Hebraic words and phrases.

Kane learned from Sula that not all of the inhabitants were of one blood; they did not mix with their black slaves, or if they did, the offspring of such a union was instantly put to death, but there was more than one strain in the race. The dominant strain, Sula learned, was Assyrian; but there were some of the people, both common people and nobles, whom Sula said were “Arbii,” much like the Assyrians, yet differing somewhat. Then there were “Kaldii,” who were magicians and soothsayers, but they were held in no great esteem by the true Assyrians. Shem, Sula said, and his kind were Elamites, and Kane started at the biblical term. There were not many of these, Sula said, and they were the tools of the priests – slayers and doers of strange and unnatural deeds. Sula had suffered at the hands of Shem, he said, and so had every other slave of the temple.

And it was this same Shem on whom Kane kept hungry eyes riveted. At his girdle hung the golden key that meant liberty. But, as if he read the meaning in the Englishman's cold eyes, Shem walked with care, a dark sombre giant with a grim carven face, and came not within reach of the captive's long steely arms, unless accompanied by armed guards.

Never a day passed but Kane heard the crack of the scourge, the screams of agonized slaves beneath the brand, the lash, or the skinning knife. Ninn was a veritable Hell, he reflected, ruled by the demoniac Asshur-ras-arab and his crafty and lustful satellite, Yamen the priest. The king was high priest as well, as had been his royal ancestors in ancient Nineveh. And Kane realized why they called him a Persian, seeing in him a resemblance to those wild old Aryan tribesmen who had ridden down from their mountains to sweep the Assyrian empire off the earth. Surely it was fleeing those yellow-haired conquerors that the people of Ninn had come into Africa.

And so the days passed and Kane abode as a captive in the city of Ninn. But he went no more to the temple as an oracle. Then one day there was confusion in the city. Kane heard the trumpets blaring upon the wall, and the roll of kettle-drums. Steel clanged in the streets and the sound of men marching rose to his eyrie. Looking out, over the wall, across the plateau, he saw a horde of naked black men approaching the city in loose formation. Their spears flashed in the sun, their head-pieces of ostrich-plumes floated in the breeze, and their yells came faintly to him.

Sula rushed in, his eyes blazing.

“My people!” he exclaimed. “They come against the men of Ninn! My people are warriors! Bogaga is war-chief – Katayo is king. The war-chiefs of the Sulas hold their honors by the might of their hands, for any man who is strong enough to slay him with his naked hands, becomes war-chief in his place! So Bogaga won the chieftainship, but it will be many a day before any slays him, for he is the mightiest chieftain of them all!”

Kane's window afforded a better view over the wall than any other, for his chamber was in the top-most tier of Baal's temple. To his chamber came Yamen, with his grim guards, Shem and another sombre Elamite. They stood out of Kane's reach, looking through one of the windows.

The mighty gates swung wide; the Assyrians were marching out to meet their enemies. Kane reckoned that there were fifteen hundred armed warriors; that left three hundred still in the city, the bodyguard of the king, the sentries, and house-troops of the various noblemen. The host, Kane noted, was divided into four divisions; the center was in the advance, consisting of six hundred men, while each flank or wing was composed of three hundred. The remaining three hundred marched in compact formation behind the center, between the wings, so the whole presented an appearance of this figure: