The Second World War (64 page)

The next convoy, PQ-17, the largest yet sent to the Soviet Union, turned into one of the greatest naval disasters of the war. Faulty intelligence had suggested that the German battleship

Tirpitz

, together with the

Admiral Hipper

and

Admiral Scheer

, had left Trondheim to engage the convoy. This prompted the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, to order the convoy to scatter on 4 July. It was a catastrophic decision. Altogether twenty-four ships out of thirty-nine were sunk by aircraft and U-boats, with the loss of nearly 100,000 tons of tanks, aircraft and vehicles. Following the loss of Tobruk in North Africa, and combined with the German advance into the Caucasus, the British began to think that they might lose the war after all. All further summer convoys were suspended, to Stalin’s great displeasure.

Once the Soviet forces on the Kerch Peninsula had been destroyed, Manstein turned his Eleventh Army against the port and fortress of Sebastopol. Massive artillery and air bombardment with Stukas failed to dislodge the defenders, who fought on from caves and tunnels deep in the rock. At one stage, the Germans are said to have used chemical weapons to dislodge them, but this is far from certain. The Luftwaffe was determined to deal with harassing attacks from Red Army bombers. ‘

We are really going

to show the Russians’, wrote an Obergefreiter, ‘what it means to play with Germany.’

Soviet partisans harried the German rear, and one group blew up the single railway track across the Perekop Isthmus. Anti-Soviet Crimean Tatars were recruited to help hunt them down. Manstein brought up an 800mm monster of a siege gun mounted on railway wagons to pound the ruins of the great fortress. ‘

I can only say

that this is no longer a war,’ wrote a motorcycle reconnaissance soldier, ‘but just the destruction of two world views.’

Manstein’s most effective tactic was to launch a surprise attack in assault boats across Severnaya Bay, outflanking the first line of defence. The soldiers and the sailors of the Black Sea Fleet fought on. Political officers summoned meetings to tell them that they had been ordered to stand and die. Anti-aircraft batteries were switched to an anti-tank role, but gun

after gun was blown out of action. ‘

The explosions blended

into a huge continuous one,’ recorded a member of the marine infantry. ‘You could no longer distinguish individual blasts. Bombing would begin early in the morning and finish late at night. Bomb and shellbursts buried men and we had to dig them out again to continue fighting. Our telephone linesmen were all killed. Soon our last anti-aircraft gun was hit. We took up “infantry defence” in bomb craters.

‘The Germans pushed us back to the sea and we had to use a rope to get down to the bottom of the cliffs. Knowing we were there, the Germans threw over the corpses of our comrades killed in the battle, as well as burning barrels of tar, and grenades. The situation was hopeless. I decided to push along the shore to Balaklava and swim across the bay during the night and escape to the hills. I organized a group of marine infantry. But we did not manage to make it for more than a kilometre.’ They were captured.

The Battle for Sebastopol lasted from 2 June until 9 July, and German losses were also heavy. ‘

I lost many comrades at my side

,’ wrote an Unteroffizier as it ended. ‘Once in the middle of a battle I began to cry for one like a child.’ When it was finally over, an exultant Hitler promoted Manstein to field marshal. He wanted Sebastopol to become the major German naval base in the Black Sea and the capital of a completely Germanized Crimea. But the vast effort to take Sebastopol, as Manstein himself observed, reduced the forces available to Operation Blau at a critical time.

Stalin received detailed warning of the coming German offensive in southern Russia by a stroke of luck, yet he rejected it as disinformation, just as he had dismissed intelligence on Barbarossa the year before. On 19 June, Major Joachim Reichel, a German staff officer carrying the plans for Fall Blau, was shot down in a Fieseler Storch plane behind Soviet lines. Yet Stalin, certain that the main German attack was aimed at Moscow, decided that the documents were fakes. Hitler was furious when told of this intelligence disaster and dismissed both Reichel’s corps and divisional commanders. But preliminary attacks to secure the start-line east of the River Donets for the first phase had already taken place.

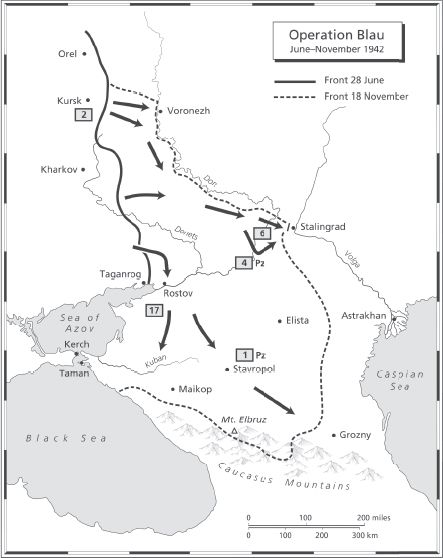

On 28 June, the Second Army and Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army attacked eastward towards Voronezh on the upper Don. The Stavka sent in two tank corps, but due to bad radio communications they milled about in the open and were gravely damaged by Stuka attacks. Stalin, finally convinced that the Germans were not heading for Moscow, ordered that Voronezh must be held at all costs.

Hitler then interfered with the plans for Operation Blau. Originally it would take three stages. The first was the capture of Voronezh. The next would see Paulus’s Sixth Army encircle Soviet forces in the great bend of

the Don, then advance towards Stalingrad to protect the left flank. At that point the idea was not necessarily to capture the city, but to reach it or ‘

at least have it within

effective range of our heavy weapons’, so that it could not be used as a communications or armaments centre. Only then would Fourth Panzer turn south to join Generalfeldmarschall List’s Army Group A in its attack into the Caucasus. But Hitler’s impatience led him to decide that a single panzer corps was sufficient to finish the battle at Voronezh. The rest of Hoth’s panzer army should head south. Yet the corps left at Voronezh lacked the strength to overwhelm the ferocious defence. The Red Army showed how obstinately it could fight back in street-fighting

when the Germans lost their advantages of armoured manoeuvre backed by air superiority.

Hitler dismissed his generals’ concerns, and at first Blau seemed to go triumphantly well. German armies advanced at great speed, to the fierce joy of panzer commanders. In the summer heat, the ground was dry and the going was good as they surged south-east. ‘

As far as the eye can see

,’ wrote a war correspondent, ‘armoured vehicles and half-tracks are rolling forward over the steppe. Pennants float in the shimmering afternoon air.’ On one day, a temperature of ‘

53 degrees in the sun

’ was recorded. Their only frustrations were that they were short of vehicles and frequently had to halt through lack of fuel.

Attempting to slow the German advance, Soviet aircraft dropped incendiaries at night to set the steppe on fire. The Germans pressed on. Dug-in Red Army tanks camouflaged themselves, but were rapidly outflanked and destroyed. Soviet infantrymen hidden in stooks of corn tried to fight back, but the panzers simply crushed them under their tracks. Panzer troops stopped in villages of thatched and whitewashed little houses, which they raided for eggs, milk, honey and fowl. Anti-Bolshevik Cossacks who had welcomed the Germans found their hospitality shamelessly abused. ‘

For the local people

, we come as liberators,’ wrote an Obergefreiter bitterly, ‘as liberators of their last seed corn, vegetables, cooking oil and so forth.’

On 14 July, forces from Army Groups A and B met up at Millerovo, but the huge encirclements which Hitler expected were not taking place. A certain realism had crept into Stavka thinking after the Barvenkovo pocket. Soviet commanders pulled their armies back before they were surrounded. As a result, Hitler’s plan to encircle and destroy the Soviet armies west of the River Don could not be fulfilled.

Rostov-on-Don, the gateway to the Caucasus, fell on 23 July. Hitler promptly ordered that the Seventeenth Army should capture Batum, while the First and Fourth Panzer Armies were to head for the oilfields of Maikop and to Grozny, the capital of Chechnya. ‘

If we don’t take

Maikop and Grozny,’ Hitler had told his generals, ‘then I must put an end to the war.’ Stalin, shaken to find that his predictions of another offensive against Moscow had been so wrong, and realizing that the Red Army lacked sufficient troops in the Caucasus, sent Lavrenti Beria down to put fear into his generals.

Paulus was now ordered to capture Stalingrad with the Sixth Army, while his left flank along the Don would be protected by the Fourth Romanian Army. His infantry divisions had been marching for sixteen days without a rest. And Hoth’s XXIV Panzer Corps, which had raced south towards the Caucasus, was now turned round to assist the attack on Stalingrad. Manstein was amazed to hear that his Eleventh Army, having secured the

Crimea, was to be sent north for a new offensive on the Leningrad front. Once again Hitler was failing to concentrate his forces, at the very moment when he was trying to seize a huge new expanse of territory.

On 28 July, Stalin issued his Order No. 227 entitled ‘Ni shagu nazad’–‘Not one step back’–drafted by Colonel General Aleksandr Vasilevsky. ‘

Panic-mongers and cowards

must be destroyed on the spot. The retreat mentality must be decisively eliminated. Army commanders who have allowed the voluntary abandonment of positions must be removed and sent for immediate trial by military tribunal.’ Blocking groups were to be set up in each army to gun down those who retreated. Punishment battalions were strengthened that month with

30,000 Gulag prisoners

up to the age of forty, however weak and under-nourished. In that year, 352,560 prisoners of the Gulag, a quarter of its whole population, died.

The brutality of Order No. 227 led to scandalous injustices when impatient generals demanded scapegoats. One divisional commander ordered a colonel whose regiment had been slow in the advance to shoot somebody. ‘This is not a trade union meeting,’ the general said. ‘This is war.’ The colonel selected Lieutenant Aleksandr Obodov, the much admired commander of their mortar company. The regimental commissar and a captain from the NKVD Special Detachment arrested Obodov. ‘

Comrade commissar I’ve always been a good man

,’ said Obodov, unable to believe his fate. ‘The two arresting officers wound themselves up into an anger, and began to shoot him,’ a friend of his recorded. ‘Sasha was trying to brush the bullets off with his arms as if they were flies. After the third volley, he collapsed on the ground.’

Even before Paulus’s Sixth Army reached the great bend in the River Don, Stalin had set up a Stalingrad Front and put the city on a war footing. If the Germans crossed the Volga, the country would be split in two. The Anglo-American supply line across Persia was now threatened, just after the British had cancelled further convoys to northern Russia. Women and even schoolgirls were marched out to dig anti-tank ditches and berms to protect the oil-storage tanks beside the Volga. The 10th NKVD Rifle Division had arrived to control the Volga crossing points and bring discipline to a city increasingly seized by panic. Stalingrad was now threatened by Paulus’s Sixth Army in the Don bend, and by Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army, suddenly sent back north by Hitler to accelerate the capture of the city.

At dawn on 21 August, infantry from the LI Corps crossed the Don in assault boats. A bridgehead was secured, pontoon bridges built across the river, and the following afternoon Generalleutnant Hans Hube’s 16th Panzer Division began to rattle over. Just before first light on 23 August, Hube’s leading panzer battalion, commanded by Oberst Hyazinth Graf Strachwitz, advanced towards the rising sun and Stalingrad, which lay

just sixty-five kilometres to the east. The Don steppe, an expanse of scorched grass, was rock hard. Only

balkas

or gullies slowed their headlong advance. But Hube’s headquarters suddenly halted, having received a radio message. They waited with their engines switched off, then a Fieseler Storch appeared, circled and landed beside Hube’s command vehicle. General Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen, the brutal and shaven-headed commander of the Fourth Luftflotte, strode over. He told Hube that on orders from Führer headquarters the whole of his air fleet was to attack Stalingrad. ‘

Make use of us today

!’ he told Hube. ‘You’ll be supported by 1,200 aircraft. Tomorrow I cannot promise you any more.’ A few hours later, German tank crews waved enthusiastically as they saw the massed squadrons of Heinkel 111s, Junkers 88s and Stukas flying over their heads towards Stalingrad.

That Sunday, 23 August 1942, was a day Stalingraders would never forget. Unaware of the proximity of German forces, civilians were picnicking in the sun on the Mamaev Kurgan, the great Tatar burial mound which dominated the centre of a city which stretched for over thirty kilometres along the curve of the Volga’s west bank. Loudspeakers in the streets broadcast air-raid warnings, but only when anti-aircraft batteries began firing did people begin to run for cover.

Richthofen’s aircraft started to carpet-bomb the city in relays. ‘

In the late afternoon

’, he wrote in his diary, ‘began my two-day major assault on Stalingrad with good incendiary effects right from the start.’ Petroleum-storage tanks were hit, creating fireballs and then huge columns of black smoke which became visible from more than 150 kilometres away. A thousand tons of bombs and incendiaries turned the city into an inferno. The tall apartment buildings, the pride of the city, were smashed and gutted. It was the most concentrated air assault during the whole war in the east. With refugees swelling the population to around 600,000, some 40,000 are estimated to have been killed in the first two days by air attack.