The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (56 page)

Read The Secret Life of Salvador Dali Online

Authors: Salvador Dali

This new and unnecessary “expense,” the moment the pleasure it afforded me was over, only accentuated for me with an intensified feeling of discouragement the intolerable reality of my financial situation. Then all my impulsive anger turned toward myself. To punish myself for having done “that,” I looked at my closed fist, the recent instrument of my enjoyment, and with it I pitilessly struck my face. I hit it several times in succession, harder and harder, and suddenly I felt that I had broken a tooth. I spat blood on the ground, on the very spot where a moment before I had squandered my treasure of pleasure. It was written: a tooth for a tooth!

I returned to our cottage, in a fever of excitement, but radiant. Victoriously I showed Gala my fist:

“Guess!”

“A glow-worm,” she said, knowing that I was fond of gathering them.

“No! My tooth–I broke my little tooth; we must by all means go and put it in Cadaques, hang it by a thread in the centre of our house at Port Lligat.”

XI. The Great Paranoiac

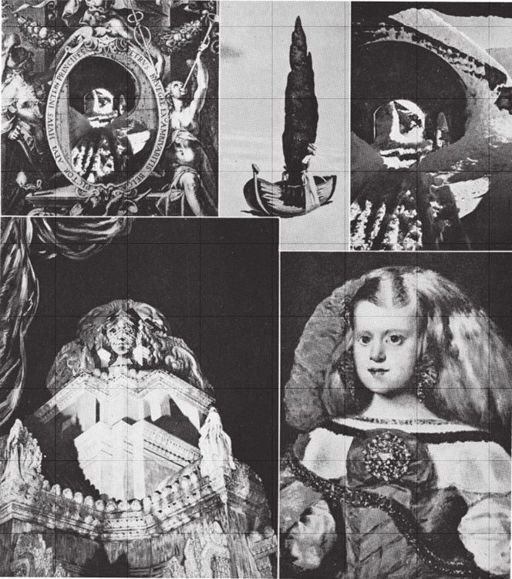

Apparition of the head of Don Quixote in an Austrian postal card.

Under this cypress, which figures in my early memories, I first read Don Quixote.

The postal card as it appeared when originally discovered by Gala.

Apparition of Velasquez’ Infanta in the summit of a piece of Hindu architecture.

Velasquez’ painting of the Infanta.

XII. The Mouth of an Aesthetic Form

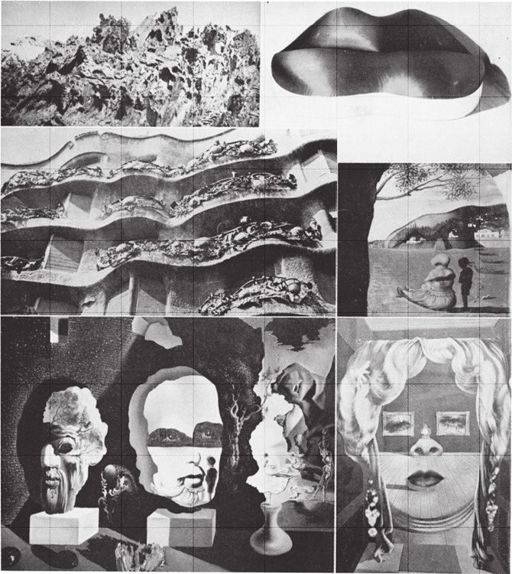

The exact spot at Cadaques, where the jagged rocks made it uncomfortable to sit, which inspired the famous Divan in the Shape of a Mouth.

My idea as realized by the decorator, Jean-Michel Frank, one of my great friends during the Paris period, who was to commit suicide almost immediately after his arrival in America.

The mouth, the sea, and its foam treated as aesthetic forms in wrought iron by the architect Gaudi of Barcelona.

Mysterious Mouth appearing in the back of my nurse.

Four Mouths or “Age, Adolescence, and Youth.”

The Face of Mae West, which might be used as an apartment.

This little tooth inspired in me a great tenderness and pity. It was tiny, so thin that it was translucid. It was like a small fossilized rice-grain, with an infinitesimal fragment of a daisy-petal caught within it. For one could in fact see a tiny whiter point at the center. Perhaps if one could have microscopically enlarged this little white spot one might have seen the aureole of a tiny Virgin of Lourdes appear. I have always had a precise consciousness of the advantage of my infirmities. In deficiencies, as a consequence of the laws of compensation, of disequilibrium and of heterogeneity, there are created breaks out of which new hierarchies of the normal coefficients of elasticity are created. I am quite aware that the Argonauts were supposed to have aggressive and well-stocked jaws, and we are told a great deal about the will logically directed toward success. But within my own experience I have never seen these strong faces with flawless porcelain teeth—prototypes of mordant tenacity—except among the anonymous crowds, capable at best of climbing to the most average situation in life. The rich, on the contrary, always have bad teeth. Money ages and wrinkles the man who is going to be rich, even before he succeeds in becoming so, just as the effluvia of certain malefic and carnivorous flowers intoxicate in advance the insect that comes to rest upon its fatal pistils. “My beloved, impoverished, uneven, decalcified teeth, stigmas of my old age, henceforth I shall have only you to bite at money!”

The following day we went to Málaga to ask for a little money of our communistically inclined surrealist friend. We took the bus, with just enough money for the one-way trip. Thus, if we did not get hold of any it would be impossible for us to come home. After looking for him everywhere we finally caught him. I said to him, “We need at least fifty pesetas to keep us for three or four days more till our money comes.” Our friend assured us that he had sent our telegram the very evening we wrote it. He had no money of his own, but he promised me that he would immediately look up the various people from whom he might borrow this sum, and that I could surely count on it. He made us sit on the terrace of a café, and while Gala had an

horchta

and I a vermouth with olives he went on his pilgrimage to find money to lend us.

It was getting close to the time our bus was to leave, and there was still no sign of our savior. We began to despair of ever seeing him again when, just at the last moment, he came running.

“Run over and get seats on the bus!” he said. “Everything is arranged. I’ll see you off.”

He saw us to our seats, and while he wiped the sweat from his face with one hand, he shook my hand with the other, in which a piece of paper was discreetly folded, and said goodbye. I thanked him with all my heart, saying, “It won’t be long now.”

He smiled to indicate that we could in any case count on him, the ous started off, and for the first time the contact with a fifty-peseta bill within my hand seemed to be imbued with all the white magic of the

earth combined. Here I held three days of the life of Gala and of Salvador Dali which I savored in advance as the most magnificent in our existence. I relaxed my hand with the deliberation of one who wants to prolong the pleasure of anticipation indefinitely, able at last to observe with his own eyes the symbol of a happiness awaited with too much anguish.

But a chill came over me when I discovered that what I had in my hand was not a fifty-peseta bill but that my friend, apparently in sarcasm and derision, had simply left me the crumpled blue receipt of the telegram which he had sent for me two days before, thus not only giving me to understand that he was not disposed to lend me the sum I had asked him for, but cynically reminding me of the debt I owed him for the telegram. We had no money to pay our bus fare, and if the conductor had asked me at that moment for the price of my ticket, I should probably have tried to kick him off the bus. Gala was aware of the danger of such fits of anger which, when they take hold of me, can lead to the most unforseen, but always catastrophic solutions. She clutched my arm, begging me not to do anything. But I had got to my feet and was looking about for some pretext to perpetrate one of my phenomenal acts. As if in mechanical obedience to my sudden anxiety the conductor rang the bell and the bus stopped. I thought for a moment that my aggressive intentions had somehow been divined and that I was going to be thrown out of the bus. With both hands I clutched one of the nickel bars, prepared for a desperate resistance. But at this moment I saw our surrealist friend come rushing toward me, looking very unhappy, and waving in his hand what this time was visibly a fifty-peseta bill. In the last-minute confusion of leave-taking he had given me the wrong piece of paper and he had followed our bus in a taxi to catch up with us. We continued on our way.

When we reached home a stack of letters bearing good news awaited us, and among them was a check from Barcelona for our money which had been transferred to a Málaga bank. I ate a couple of anchovies with tomatoes and slept the whole afternoon with a sleep as heavy as the somnambulist noon-day bus that had brought us back. When I awoke, a moon that was red as a slice of watermelon rested on the fruit-dish of the bay of Torremolinos cut off by the window-frame and seemingly standing right on the table. My sudden awakening gave to this combination of images a confused synthesis in which the real spatial relationships began only gradually to organize themselves. I could not tell a

priori

what was near and what was far, what was flat and what was in perspective. I had just seen photographically a picture of the type of Picasso’s cubist windows, a picture which, evolving in my brain, was to become the key to the mimetic and paranoiac images I was later to produce, like my bust of Voltaire. While I lay on my bed reflecting upon all these complicated problems of vision, which are essentially philosophical problems, my finger was pleasurably exploring the inside of my nose, and I pulled out a little pellet which struck me as too large to be a piece of dry mucus. And upon examining and compressing it with delicate attention I discovered that it was in fact a piece of the telegram receipt which I must have pressed, rubbed and rolled into a ball with the sweat of my hand and absentmindedly stuck in one of my nostrils, an automatic bit of play which was characteristic of me at that period.

Gala was again unpacking our baggage, with the evident intention of staying, since we had received the money. But I said,

“We’re leaving for Paris!”

“Why? We can have the benefit of another two weeks here.”

“No! The other evening when I left slamming the door, I saw a slanting ray of sunlight pierce through a shred of cloud. Just at that moment I was in the act of ‘spending’ my vital fluid. It was after this that I broke my small tooth. You understand? I had just discovered in my own flesh the ‘grandiose myth’ of Danaë. I want to go to Paris, and I want to make thunder and rain. But this time it’s going to be gold! We must go to Paris and get our hands on the money we need to finish the work on our Port Lligat house!”

We went back to Paris, stopping only as long as we had to in Madrid and Barcelona, and two hours in Cadaques to go and look at the effect of our house for a moment. This effect was even poorer and more cramped than we had expected—it was practically nothing. But already in this almost nothing there was the mark of the fanaticism of the two of us, and for the first time I was able to observe a structural reality in which Gala’s clear, concrete and trenchant personality pierced through the defective delirium of my own. There were only the proportions of a door, a window and the four walls, and already it was heroic.

But true heroism awaited us in Paris, where Gala and I were to endure the hardest, tensest and proudest effort in the day-to-day defense of our personality. Everyone around us betrayed without greatness, the anecdote devoured the category, and as my name progressively affirmed itself with the indestructible grip of a cancer in the bosom of a society that did not want to hear about it, our practical life grew increasingly difficult. It was as if people were reacting to the horrible disease of my intellectual prestige, which was demolishing and destroying them, by communicating to me that disease of which they alone possessed the germs—the continual gnawing of “financial worries.” I preferred this disease to theirs. I knew it was curable.