The Setting Sun (21 page)

Authors: Bart Moore-Gilbert

‘Then you absolutely must look up an old friend of ours, Farrokh Cooper. He runs a big engineering works down there. His father was the first Indian prime minister of Bombay, before the war. He’d be delighted to help you. I’ll ring him right now and let him know you’re coming.’

Any remaining doubts about the next stage of my trip dissolve. It’s as if it’s all been planned. Above all, I’m immensely reassured by Dhun’s account of Keki’s relations with Bill. This is what I’d hoped to hear from Modak. It’s the first unambiguously positive account of Bill this whole trip. Maybe the pendulum’s beginning to shift, after all the allegations in Shinde and

Sentinel

. Still, nagging doubts remain. Keki worked with Bill well after Satara, and in completely different circumstances. Pursuing the Parallel Government and preventing communal massacres are chalk and cheese.

Erna returns from the adjoining room a few minutes later. ‘I phoned Farrokh and he’s going to book you into the Regency. He says it’s the only decent place in Satara. How are you getting there?’

‘Bus, I guess.’

Erna looks concerned. ‘Have you travelled on Indian buses?’

I smile complacently. ‘It’ll be an adventure.’

She seems dubious. ‘Have you reserved?’

‘Thought I’d wander over in the morning.’

‘No time like the present. They can fill up. I’ll take you down to Swargate and drop you afterwards. I insist.’

Before I leave, I show them my collection of photocopies. Dhun looks fondly at Bill, but she doesn’t recognise Beryl or Maria.

‘Do you know if he had an Indian girlfriend?’

Dhun ponders. ‘I seem to remember something about the

sister of the Gaekwad of Baroda. But I don’t know if it was romantic.’

Nothing’s too much trouble for Erna. She ferries me in her tiny car to the bus station and supervises my purchase of a ticket on the next day’s ‘Volvo’, as inter-city buses are apparently known here – she point-blank refuses to let me catch anything else. Then she drives to an ATM before leaving me at the Samrat.

‘You really must stop for longer on your way back,’ she says. ‘Give my mother time to try and remember more. It’s all so long ago now. We’d love to have you for dinner and really talk.’

I watch Erna’s tail lights disappear with a feeling of regret. How generous people are here. Even Modak, whom I can’t really make out, has gone to trouble to smooth my way. Why, if he was so hostile to Bill?

I’ve barely shut the door to my room when there’s a knock. It’s Anders, in a damp t-shirt, the lower half of his body wrapped in a towel.

‘Can you help me out, man? Soon as I got in from the bar, I washed all my clothes in the sink. This American chick I met just rang. Wants me to come over to her hotel. But my only trousers are wet and I can’t go out to buy some more.’

We’re roughly the same build. Laughing, I show him what I have. ‘Make sure you don’t stay out the night,’ I add mock-solemnly. ‘I’m leaving at six-thirty tomorrow morning.’

CHAPTER 8

The Ghosts of Satara

From Swargate, the ‘Volvo’ grinds its way through ugly, gridlocked suburbs until eventually we reach the new dual carriageway running south to Bangaluru. There’s no hard shoulder, however, and the inner lane’s choked with pedestrians, bicycles, auto-rickshaws, motorbikes and herds of animals. Rural India, vast as it is, seems to be disappearing apace, Pune’s tentacles spreading far along the motorway, small hotels in bare plots, half-finished filling stations, stalls with shining produce which women risk their lives to lean out into the hurtling traffic and wave imploringly. The bus barrels along in the overtaking lane, darting inside when it’s hogged by labouring trucks, some piled high as double-deckers with precarious arrangements of sacks and crates. The countryside becomes increasingly parched and dun as we approach a series of ridges. We climb steepling passes, one after another, where the road shrinks to a single lane of lurching hairpin bends and ill-tempered klaxons.

Four hours later, as we descend the last incline towards Satara, the landscape changes markedly again. The plain in which the city’s situated is a lush patchwork of emerald sugar cane and jade orchards, extending as far as the eye can see. The temperature’s warmer and the air seems softer, too, more like the tropics than Pune. I’m dropped at a busy intersection and hop into an auto-rickshaw, where I’m suddenly overcome by nerves. At last I’ve reached the main theatre of action, the seeming pinnacle – or nadir – of Bill’s Indian career.

First impressions of Satara are positive. Seen from the broad, tree-lined approach road it’s much less ugly and polluted than

Pune, and has more the character of a country town. There are even bullocks grazing in the middle of the final roundabout out of which, of all things, a fifteen-foot replica Eiffel Tower soars. Looming over everything, a mile or so beyond, is a fort on a cliff-encircled height. It’s the one on the cover of Modak’s memoir, but now with spindly telecommunications masts jutting out of it. What did Bill feel when he first entered Satara, charged with his onerous brief? Perhaps the same mixture of excitement and apprehension as grips me now.

At last I’m somewhere Bill spent significant time. My sense of connection with him intensifies when I get to my room, at the top of the eight-storey hotel. It’s not as nice as the one in Pune, but has the great advantage of a balcony. I step outside with the bellhop and he points out the police headquarters, way down to the left, half hidden by a dense canopy of trees. Beyond is a collection of miniature yellow buildings, like children’s blocks from this distance, which he tells me is the Rajah’s ‘new’ palace, built in the eighteenth century. North and west, the eroded flanks and flat-topped bluffs of the Sahyadris rise through the dancing haze like buttes in a western. I wonder which of those hills Bill scoured, which ribbon roads below he raced along in his ‘Woodie’.

After lunch I take another auto-rickshaw to the police station, about a mile away. We pull up at an imposing, double-storeyed building made of dark laterite blocks. The veranda which Hobson took Modak out onto in

Sentinel

, immediately before Bill’s arrival, runs the length of the first floor to massive turrets at each end. ‘Satara Police 1913’ is painted in blue and white, next to a long run of Marathi letters in golden plastic above the main entrance. A khaki-clad constable shows me into a ground-floor room where his superior examines Modak’s card, before sending him off with it again. Phones ring and intercoms crackle. I wait, inhaling the aroma of bodies and masala tea, under the curious eyes of half a dozen policemen and some anxious-looking

civilians. Was this the duty room in Bill’s day, too? There’s a large map of Satara District on one wall, subdivided in different colours. Everything’s in Marathi, so I can’t read it; but I try to guess which are the villages which Shinde and Modak mention.

A pretty woman constable enters, and motions me to accompany her. How many times did Bill stride up these very stairs? On the first floor, she knocks at a door and opens it to reveal a sleek-skinned, smiley man of about forty, with film-star teeth. He’s holding Modak’s card.

‘Deputy Superintendent Kulkarni,’ my escort announces, saluting him crisply.

He stands up to shake hands, before motioning me to a chrome chair at his imposing desk. I look at the name boards. They’re in English, and list every DSP since the station opened. Some of the names are familiar: de Vere Moss, principal of the PTS when Bill was there, had charge earlier in the 1930s, following Freddie O’Gorman, Modak’s favourite inspector-general. Later come C.M. Yates, about whom

Sentinel

’s so rude, and Modak’s bête noire, James Hobson. After 1945, all the names are Indian; they include Dhun’s husband, K.J. Nanavatty. But here’s a surprise: there was an Indian in charge as early as 1929. Perhaps the IP was more progressive than Modak’s given it credit for.

‘DSP Mutilal’s out of station just now. But he’s given instructions about your visit. So your father worked here?’

I point to the board. ‘Special additional superintendent under Hobson.’

Kulkarni reaches across the desk and shakes my hand again. ‘Privileged to meet you.’ He nods emphatically. ‘Tea?’ My host shouts for an attendant and settles back in his seat, asking about Bill’s career. When I mention the Parallel Government, he laughs, as if it’s a great joke. There’s a knock at the door and another officer enters, swagger stick under one arm. Kulkarni rises and salutes.

‘Mr Sanjay Shinde. He’s the ASP these days.’

Shinde’s a slimmer and smarter version of Kulkarni, with an equally luxuriant moustache. He beckons me to a sofa beneath the name boards, where he examines my visiting card while I wonder anxiously whether he’s related to Bill’s chief accuser.

‘So you are professor of English at the London University?’

I nod.

‘I studied literature, too. You like

Crime and Punishment?

My favourite work of all time.’

We discuss books. Shinde’s very well read, and his English is excellent; this he attributes to a lengthy spell in Kosovo as part of the UN peacekeeping force.

‘First time I understood the position of Muslims in Europe,’ he comments. ‘Made me see their situation here in a new light.’

Before I can ask him to explain further, he inquires about my trip.

‘This would have been your father’s office,’ Shinde declares, when I’ve repeated my story. ‘Unless he was given Mr Modak’s when he arrived?’

If so, I’m sure Bill’s colleague would have mentioned this additional irritant. I look round hungrily, trying to work out what’s survived from the 1940s. The noisy ceiling fan, perhaps, spinning lopsidedly? And was this teak desk where Bill mapped his operations? I ask what problems today’s police face.

‘Quieter than your father’s time,’ Kulkarni laughs, flashing his teeth.

‘When you have democracy, it’s never quiet,’ Shinde adds. ‘When you don’t have democracy, it’s never quiet. Same as your father’s time, there are always agitators waiting in the wings. We’re worried about reprisals for the attacks in Mumbai.’

‘Are there many Muslims here?’

‘Not as many as before,’ Shinde says. ‘Too many politicians make political capital out of them. And out of incitement

against Hindus from other parts of India. They make a mockery of the Constitution.’

‘Money’s short, as well,’ Kulkarni complains. ‘We don’t have the resources to do our job properly.’

Shinde nods. ‘Especially vehicles. Spares always a problem. Would you like to look around?’ he suddenly asks, as if this is why he’s come by.

I’m taken back downstairs and through an arch to the rear of the building. We pass a cabinet of tarnished sports cups and another filled with ancient weapons, muskets and crude-looking pistols.

‘Home-made, seized from

goondas

over the years,’ Shinde explains.

Did the Parallel Government rely on such crude equipment? Out back are perhaps two acres of crushed murram. A squadron of women recruits in white tops and khaki trousers wheels about to an instructor’s bark. Beyond, rows of tiny cottages slope away, like the game scouts’ lines I remember from Tanganyika.

‘Other ranks’ housing,’ Kulkarni confirms.

I take the cue. ‘Are there any old constables around still from my father’s time?’

Shinde ponders a moment. ‘We don’t have lists. The pension people in Mumbai will know.’ Catching my look of disappointment, he smiles. ‘I’ll ask. How long are you staying?’

‘It depends. I’m waiting to hear from a friend.’

He nods.

‘Two names I have from that time are Gaikwad and Pisal. I’d be particularly interested to track them down.’

Kulkarni jots the names in his notebook. Next I ask about the confidential weekly reports. Both men again look doubtful but promise to inquire.

‘Mr Modak also said that every main police station keeps Part IV records. Could I possibly see the ones from that time?’

Shinde’s eyes light up. ‘You mean our annual reports?

Summaries of trends? You’ll have to ask when Mr Mutilal gets back tomorrow.’

I comment on the military feel of the station. Kulkarni explains that the old Bombay Police was modelled on the nineteenth-century Irish constabulary, and the modern force has retained its khaki uniform. It seems an ominous precedent.

We’re now outside a long hangar-like building to one side of the parade ground, with a shallow-pitched roof of corrugated iron. The sky above’s a flawless blue. Shrieking harlequin parakeets tumble through the flame trees behind, scattering orange blossom on the ground. An enormous grey lizard watches warily from its rock while a mongoose scuttles past. Rikki-Tikki-Tavi. I remember arriving in Durham for undergraduate studies, how alien it seemed after the southern England I’d slowly grown used to. What must Bill have felt, a wide-eyed nineteen-year-old, coming to such a wildly different place?

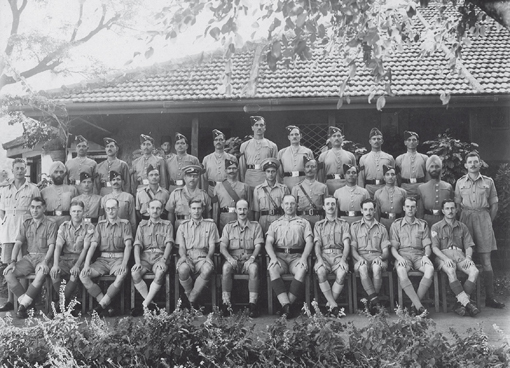

Army liason, 1945 – Bill front row, fifth from left

‘Will you say something to the men?’ Shinde suddenly asks.

I’m startled. ‘Which men?’

‘We have a cadre of constables passing out this week. A few words, please, Professor, before their class?’