The Story of French (58 page)

Read The Story of French Online

Authors: Jean-Benoit Nadeau,Julie Barlow

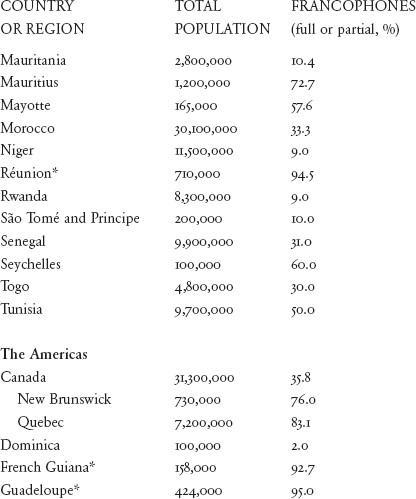

In America, French owes its survival to the complicated geopolitics of the second half of the eighteenth century and, now, to the cultural fortitude of Quebec and Acadia. What will happen if the proportion of francophone Canadians slips to twenty percent? And what if Quebec separates from Canada? What will happen to francophones in other parts of Canada? They may indeed assimilate quickly, like the Franco-Americans and the Cajuns of yesterday. On the other hand, other French-speaking communities on the continent may bolster them. French is now an official language in New Brunswick, and who could have predicted that the number of native French speakers would be rising in California and in Florida, a state that is attracting both Haitians and Quebec “snowbirds”—many of whom are counted in census statistics?

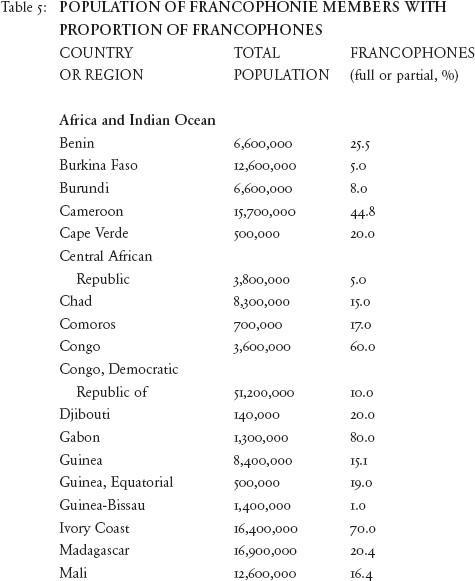

Africa forms the biggest pool of French speakers and has the most potential for growth in the francophonie. If birth rate alone is considered, the number of francophones could potentially double in twenty-five years. In North Africa, French is doing well everywhere, but much depends on whether the sub-Saharan countries can improve their education systems and economies. As a French teacher from Togo told us, “

Le français ne fait plus vivre son homme

” (“French no longer provides a living”). Only twenty-five percent of Africans are fully schooled, and this proportion is dropping every year, but—a promising change—the proportion of women among those who are fully schooled is rising rapidly. This could reinforce French in African households and eventually make it a mother tongue rather than a learned language. In Mauritius an unexpected turn of events is shaking up the anglophone elite: Most of the Creole population is now schooling itself in French universities in Réunion, and eighty percent of the newspapers are now in French. This rising class of francophones nurtures the ambition of making Mauritus the Hong Kong of the Indian Ocean.

Although much of the future of French depends on what happens in Africa, the language is vulnerable to the vagaries of France’s foreign policy there. Any move by the French has the potential to attract or alienate people. One Senegalese author, Boubacar Boris Diop, stopped writing in French and turned to his Wolof mother tongue as a result of France’s shady actions in Rwanda. The gesture, though symbolic, is an isolated one for the moment, but it could catch on. More seriously, French made progress in post-colonial Africa because it was perceived as the language of development; as the continent continues to stagnate and even regress, will French still be considered useful? It’s hard to predict.

The fringes of the French-speaking world are equally interesting. More French is spoken in Israel than in Louisiana (in both percentage and number of speakers), and Israel could well join the Francophonie if it manages to bury the hatchet with Lebanon (which opposes Israel’s candidacy). French is spoken more in the United States and in Mexico than it is in some member countries of the official Francophonie, namely Bulgaria or Albania. Who knows where that will lead? Enrolment in programs of the Alliances françaises and French

collèges

and

lycées

is increasing. And the inroads made by the Agence universitaire francophone in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia show there is still interest in the language there.

In the end, the future of French will depend on a simple question: How useful will French be to its native speakers, partial speakers and francophiles? Very few people ever learn a language just because it is beautiful. People will continue to learn and maintain French only if it provides them with access to things that are useful, productive, challenging or beautiful. That is why this book has focused on the decisions and policies, creations and inventions, achievements and failures that have shaped the destiny of French, as opposed to strictly linguistics.

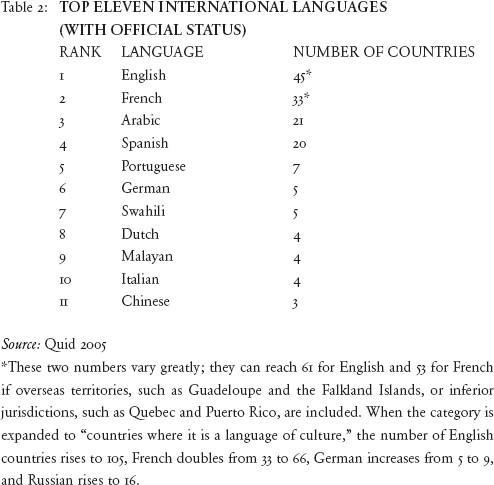

Statistics show that the use of French in international organizations puts it on a second tier all of its own, well below English, but well above all other international languages in terms of use and learning. Fatalists view this placement not as a tier but as the first step towards free fall. But global statistics on the teaching of French as a second language indicate that French remains solidly established as the

other

global language.

The future of French also depends on individual efforts and initiatives in research, in business, in arts and culture. Business, science and diplomacy have to be carried out in French if it is to remain a language of science, business and diplomacy. At the moment, the elites of many countries are still turning to French because it is the best way to access knowledge, science and business. In some areas of excellence French remains not only useful but necessary, namely mathematics, biology, biomedical research, oceanography and nuclear research. The threat to French right now is not so much English as the mediocrity of the French university system and of the French press in general (French dailies have very low circulation). However, these things are due more to policy decisions than to lack of cultural dynamism, and are reversible.

In diplomacy, the Francophonie’s push for plurilingualism and cultural diversity may reap very big rewards. These policies may well be what francophone countries need in order to create a vast economy of culture, but also to become a model themselves. In the Renaissance, people learned Italian because Italian cities were centres of cultural and scientific renewal, not because they were powerful. In the twenty-first century, many people could turn to French because the Francophonie represents the most articulate and progressive alternative to the global American village.

For all we know, French could outlast English. Pop historians of the English language never fail to draw parallels between the triumphant destiny of English and that of Latin during the Roman Empire. But they rarely point out that Roman patricians spoke Latin with a Greek accent, primarily because the Romans looked to the Greeks for culture, knowledge and education; their children were schooled by Greek instructors. And as the western Roman Empire collapsed, only the eastern, Greek-speaking side remained, and Byzantium outlived the Roman Empire by another eight centuries.

The question that motivated this book was why French has maintained its influence in spite of the domination of English. But many linguists point out that the position of English is not as solid as it appears. According to linguist David Graddol, who did two studies of English for the British Council, English may well be the world’s lingua franca, but native anglophones may end up being victims of their language’s success. As more of the world speaks English, monolingual English speakers may lose their competitive edge to English speakers who also master other languages, particularly since, as Graddol argues, the more people speak English, the less relevant the norms and standards of the language will become. The belief that English is the language of business, science and diplomacy has been beneficial for English to a point, but it has come at a price: that of making Anglo-American scientists, businessmen and diplomats oblivious to the fact that good science, business and diplomacy are also being conducted in other languages. It can be lonely at the top, and ivory towers are brittle. Linguist Jean Michel Eloy jokes that the best language for business is the language of the client, and this may not do English any favours in the future. Who remembers that nobody at the U.S. embassy in Iran in 1979 spoke Farsi—at the very moment of the Iranian revolution? The language of the client….

The story of French has been, and will continue to be, one of living dangerously. Spoken on many continents by relatively few people, the language is spread much thinner than Spanish, Arabic or Portuguese, but distributed more widely. Outside of France, only minorities speak French. More often than not, only the elite master the language, and the bulk of the population is only partly French-speaking at best. This can be viewed as a sign of decadence or as a starting point. Outside of France, Belgium, Switzerland and North America, French is learned as a second language rather than a mother tongue, and most of the French-speaking elites are in fact bilingual, if not multilingual. Because of this precarious situation, French could be wiped out within several generations. But it also could mean that French is in a better position to reach out and spread its influence almost everywhere on the planet.

This linguistic archipelago, this Polynesia of French, is a return to the situation of French five centuries ago, when only fringe groups of urbanites and

lettrés

spoke the language. The pessimistic see this as a sign of decline. But it could as easily be a condition for French’s renewal, a second youth. Much will depend on whether francophones—including the people of France—are able to capitalize on their situation and summon up some ambition.

All of which is to say, the most fascinating chapters of the story of French have yet to be told.

Appendices

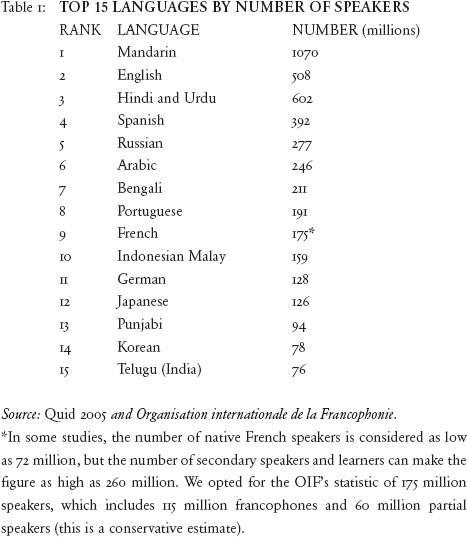

Note: All figures are estimates because the definitions of what constitutes a speaker or category of speaker (native, second language, foreign language, true speaker, partial speaker, etc.) vary from study to study.