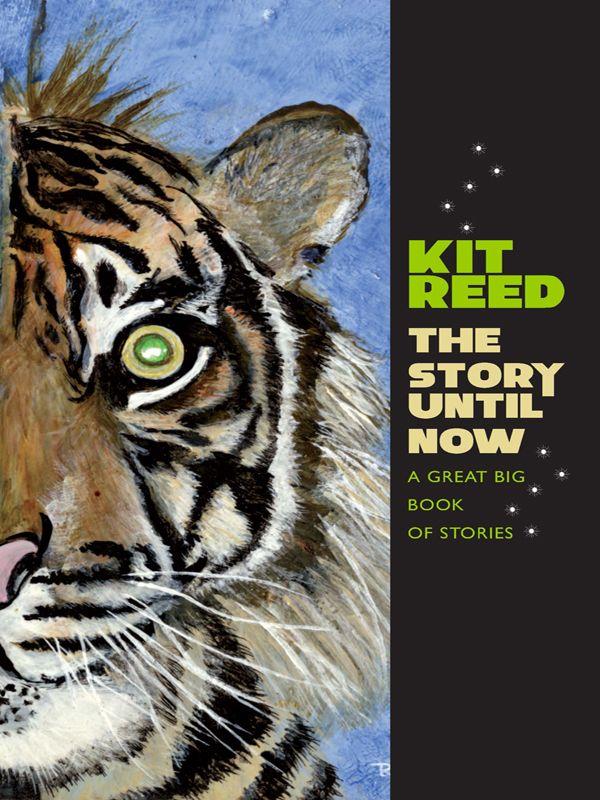

The Story Until Now: A Great Big Book of Stories

Read The Story Until Now: A Great Big Book of Stories Online

Authors: Kit Reed

The Story Until Now

Also by Kit Reed

NOVELS

Mother Isn’t Dead She’s Only Sleeping

At War As Children

The Better Part

Armed Camps

Cry of the Daughter

Tiger Rag

Captain Grownup

The Ballad of T. Rantula

Magic Time

Fort Privilege

Catholic Girls

Little Sisters of the Apocalypse

J. Eden

@expectations

Thinner Than Thou

Bronze

The Baby Merchant

Enclave

SHORT STORIES

Mr. Da V. and Other Stories

The Killer Mice

Other Stories and The Attack of the Giant Baby

The Revenge of the Senior Citizens *Plus*

Thief of Lives

Weird Women, Wired Women

Seven for the Apocalypse

Dogs of Truth

What Wolves Know

Wesleyan University Press

Middletown CT 06459

© 2013 Kit Reed

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed by Katherine B. Kimball

Typeset in Minion by A. W. Bennett, Inc.

Wesleyan University Press is a member of the Green Press Initiative. The paper used in this book meets their minimum requirement for recycled paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Reed, Kit.

The story until now: a great big book of stories / Kit Reed.

p. cm.

ISBN

978-0-8195-7349-0 (cloth: alk. paper)—

ISBN

978-0-8195-7350-6 (ebook)

1. Science fiction, American. I. Title.

PS

3568.

E

367

S

76 2013

813′.54—dc23

2012026804

5 4 3 2 1

For Joe,

who’s been in this with me from the beginning

Contentswith much, much love

Scoping the Exits: The Short Fiction of Kit Reed

GARY K. WOLFE

Journey to the Center of the Earth

The Short Fiction of Kit Reed

GARY K. WOLFE

There has always been an oddly passive-aggressive relationship between American literature and the fantastic. Almost from the beginning, a familiar myth has been the notion of bringing order to wilderness, of subduing chaos, of constructing a rational society and rational institutions, of building roads and cities and eventually suburbs and high-rises and shopping malls. But the unsubdued aspects of wildness have an unsettling way of reasserting themselves; the cities and suburbs can

become

their own sort of wilderness; the roads can seem to lead nowhere; the rational society can become a dystopia. Fantastic literature, whether it takes the form of the Gothic, of science fiction, or of fantasy, is at its best a literature that explores

implications

, that aggressively excavates the assumptions behind our sunny plans and rational dreams and shows us where they might

really

lead. This is one reason the fantastic has been such a persistent strain in American writing, from Hawthorne and Poe and Melville through Twain and L. Frank Baum up to H. P. Lovecraft and Robert A. Heinlein.

By the time we get to the last two writers on that list, however, an odd thing had begun to happen to American fantastic literature: it had begun to calve off genres, modes of writing that appealed to specific audiences and markets with particular tastes and desires. Usually, when we think of fantastic literature today, we think in terms of those genres, particularly science fiction, fantasy, and horror. But at the same time, there has been a persistent tradition of fantastic writing that doesn’t easily fit into convenient categories, but that makes use of their unique resources. This is a broader tradition than we might at first think, and has deeper roots; it’s one of the reasons we can find the occasional fantastic tale by Henry James, Edith Wharton, or Willa Cather. Even after the rise of the pulp magazines and paperbacks that helped define the pop genres, this kind of free-range fantastic continued to appear in the literary or general-interest magazines and mainstream publishing lists, and as late as the 1940s we

can find examples of it in the work of writers as diverse as John Collier, Truman Capote, John Cheever, Robert Coates, Roald Dahl, and Shirley Jackson.

This, I think, is the sort of literary space that much of the work of Kit Reed occupies. She has not been averse to publishing her stories in genre magazines such as

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction

or

Asimov’s

(along with venues such as

The Yale Review

or

The Village Voice Literary Supplement

—all are represented in this collection), but by the time her career began, toward the end of the 1950s, some of those genre-based magazines had begun to broaden their scope to include the literary fantastic, while many of the mainstream fiction markets either folded entirely (

Collier’s

or

The Saturday Evening Post

) or turned to what Michael Chabon has described as “the contemporary, quotidian, plotless, moment-of-truth revelatory story.” It may be no coincidence that Shirley Jackson published her last

New Yorker

story in 1953 and her first in

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction

in 1954—or that it was the latter magazine which published Reed’s first story, “The Wait,” in 1958. This disturbing tale of a mother and daughter trapped in a strange town with an even stranger ritual might well have appeared in

The New Yorker

nine years earlier, when it published Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” a tale with which it clearly resonates, but by 1958

The New Yorker

had largely moved away from any trace of the fantastic.

Reed’s near-legendary reputation may have to do in part with the simple fact that her career began with such an accomplished story more than a half century ago, but it has more to do with how she has continued to produce such stories with astonishing regularity ever since, never quite falling into any particular genre but never quite getting trapped by mainstream literary fashions such as the quotidian moment-of-truth tradition that Chabon describes. She has never stopped being a bit of a rebel with a unique and sometimes quirky voice, and this may occasionally have landed her in the interstices between various fictional categories (the term she uses for herself, and possibly invented, is

trans-genred

). It was probably to her advantage that some of the most visionary editors in science fiction in the 1960s and 1970s were actively on the prowl for such distinctive voices—not only Anthony Boucher, Robert Mills, and Avram Davidson at

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction

, but Michael Moorcock at

New Worlds

, Damon Knight in his series of

Orbit

original anthologies, Harry Harrison in

Nova

, and others.

Reed’s mordantly satiric and sharply funny take on beauty pageants “In Behalf of the Product,” with its devastating final line, was written for an anthology edited by Thomas M. Disch, a writer whose acerbic sensibility and finely tuned prose sometimes resembled Reed’s. He must have found the story

absolutely delicious, because up until then no one would have expected a dystopian tale about beauty queens, just as no one expects the Spanish Inquisition. But story after Reed story comes blustering into the room like those Monty Python characters, frequently offering the same sort of ominous-but-absurd comic edge. For a while in the 1960s this sort of thing was called Black Humor, another movement in which Reed both does and doesn’t belong. Even some of her more recent stories take such delirious riffs on popular culture and current events that parts of them would hardly be out of place in stand-up comedy. The Sultan of Brunei buys a bankrupt Yankee Stadium in “Grand Opening” (after Americans finally came to realize that baseball is boring) and turns it into a gigantic mall whose grand opening features a ritualized tribute baseball game with an aging Salman Rushdie throwing out the first pitch while being stalked by an equally ancient assassin, apparently the only one who didn’t get the memo about the

fatwah

being over. “On the Penal Colony” similarly rams together wildly disparate elements such as ill-conceived correctional systems and tacky historical reenactment tourist traps, with nods to both H. P. Lovecraft and the Kafka story whose title it nearly borrows: here, prisoners are sentenced to serve as historical actors in a Salem-like historical village called Arkham, though some particularly gruesome punishments are part of the system as well. “High Rise High,” one of her most famous stories, borrows elements of every school-rebellion move ever made, from

Zero for Conduct

to

Rock ’n’ Roll High School

, with elements of

Escape from New York

thrown in: the school of the title is essentially a maximum security prison sealed from the outside world in order to let intransigent students run wild apart from society—until they start in on hostages, kidnappings, and raids into local neighborhoods.