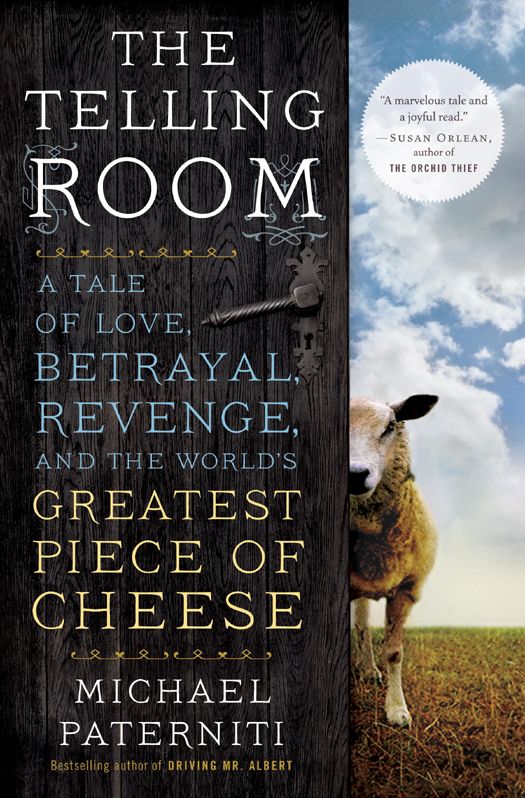

The Telling Room: A Tale of Love, Betrayal, Revenge, and the World's Greatest Piece of Cheese

Authors: Michael Paterniti

The Telling Room

is a work of nonfiction.

Some names and identifying details have been changed.

Copyright © 2013 by Michael Paterniti

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by The Dial Press,

an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

D

IAL

P

RESS

and the H

OUSE

colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Map and illustrations on

this page

,

this page

,

this page

,

this page

, and

this page

copyright © 2013 by Benjamin Busch. Used by permission. Photos on

this page

and

this page

copyright © 2013 by Gerry Hadden. Used by permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Paterniti, Michael.

The telling room : a tale of love, betrayal, revenge,

and the world’s greatest piece of cheese / Michael Paterniti.

pages cm

eISBN: 978-0-8129-9454-4

1. Cheesemakers—Spain—Guzmán—Biography.

2. Cheesemaking—Spain—Guzmán—History.

3. Guzmán (Spain)—Biography.

4. Paterniti, Michael—Travel—Spain—Guzmán. I. Title.

SF274.S7P37 2013

637’.3092—dc23 [B] 2013001430

Cover design: Kimberly Glyder

Cover photograph: © Daniel K. Gebhart/Sodapix/Corbis (sheep)

v3.1

Let us be confident

:

There will be no truth

In anything we think

.

—A

NTONIO

M

ACHADO

1991

“It sat silently, hoarding its secrets.”

T

HIS PARTICULAR STORY BEGINS IN THE DUSKY HOLLOWS OF

1991, remembered as a rotten year through and through by almost everybody living, dead, or unborn. I’m sure there were a few who had it good, maybe even made millions off other people’s misfortune, but for the rest of us, there wasn’t a glimmer. January dawned with tracers over Baghdad, the Gulf War. It was a bad year for Saddam Hussein and the Israeli farmer (Scud missiles, weak harvest), the Politburo of the Soviet Union (dissolved), and the sawmills of British Columbia (rising stumpage fees, etc.). An estimated one hundred and fifty thousand people died in a Bangladeshi cyclone. The IRA launched a mortar attack on 10 Downing Street, shattering the windows and scorching the wall of the room where Prime Minister John Major was meeting with his Cabinet (“I think we’d better start again, somewhere else,” said the prime minister). In the Philippines, Mount Pinatubo erupted, ejecting 30 billion metric tons of magma and aerosols, draping a thick layer of sulfuric acid over the earth, cooling temperatures while torching the ozone layer.

It was a brutal year for the ozone layer.

Here in America, it was no better: the rise of Jack Kevorkian, Magic Johnson’s HIV diagnosis, Donald Trump’s dwindling empire. Rape, mass murder, and masturbation.

*

The country slopped along in a recession, and meanwhile, I wasn’t feeling so good myself.

To kick things off, I got dumped in January. I was twenty-six years old, making about $5,000 a year, pretax. I lived in a two-bedroom apartment in Ann Arbor, Michigan, with my roommate, Miles, both of us graduate students in the creative writing program for fiction, a.k.a. Storytelling School. We each had a futon and a stereo—and everything else (two couches, black-and-white TV, waffle iron) we’d foraged from piles in front of houses on Big Trash Day.

That year, I toted around a book entitled

The Great Depression of 1990

, one bought on remainder for a dollar, and that predicted absolute global meltdown …

in 1990

. But I, for one, wasn’t going to look like an idiot if it hit a year or two late. The advantage I had over most everyone else in the world was my lack of participation in the economy, except to issue policy statements, from the couch, before our blizzardy TV screen of black-and-white pixels. The eleven o’clock news brought us Detroit anchorman Bill Bonds and all the bad acid and strange perversions of the year—the William Kennedy Smith trial, the Clarence Thomas hearings, the Rodney King beating—all delivered from beneath his superb toupee, woven it seemed with fine Incan silver.

Nineteen-ninety-one was the year we were to graduate, and as the months progressed toward that spring rite of passage, a funny thing happened: We, the storytellers, could not get our stories published—

anywhere

. We typed in fits of Kerouacian ecstacy, swaddled our stories in manila envelopes, sent them out to small journals across the country. The rejections came back in our own self-addressed envelopes, like homing pigeons.

So we stewed in our obscurity—and futility. We were Artists. We

worked as course assistants and teachers of Creative Writing 101, reading Wallace Stevens poems to the uvulas of the yawning undergrad horde, moving ourselves to inspiration while the class spoke among itself. We kept office hours in a holding pen with sixteen other teachers, and then went and drank cheap beer at Old Town Tavern, swapping lines from our rejection letters. As it began to dawn on us that the end of our cosseted academic ride was near, the tension ratcheted so high that we started spending extra time with the only people who were consistently more miserable than we were: the poets.

In pictures from our graduation, we—my posse and I—look so innocent, like kids really, kids with full heads of hair and skinny bodies and a glint of fear in our eyes, gazing out at the savage world and our futures. You can almost see our brains at work in those photos, now just hours away from the cruelest epiphany: Those preciously imagined short story collections and novels, copied and bound lovingly at Kinko’s, called

The Shape of Grief

or

What the Helix Said

,

†

qualified us for, well, almost … exactly …

nothing

.

Which is what led me to a local deli, a place called Zingerman’s, to see if they needed an extra sandwich-maker on weekends. This was Zingerman’s before it did $44 million in annual sales and possessed a half million customers, but it was already an Ann Arbor legend, a fabled arcade of fantastic food, a classic, slightly cramped New York–style deli in the Midwest, with a tin ceiling, black-and-white tiled floor, and the yummiest delicacies from around the world. The shelves overflowed with bottles of Italian lemonade, exotic marmalade spreads, and tapenades. The brothy smell of matzo ball soup permeated the place. On Saturday mornings, before Michigan football games, people thronged, forming a line down Kingsley Street. The sandwiches cost

twice as much as anywhere else, and whenever we splurged as students, we’d go there and stand in the long line, the longer the better actually, just to prolong the experience. Then we’d order from colorful chalkboards hung from the ceiling, detailing a cornucopia of sandwiches with names like “Gemini Rocks the House,” “Who’s Greenberg Anyway?,” and “The Ferber Experience,” each made on homemade farm bread or grilled challah or Jewish rye, stuffed with Amish chicken breast or peppered ham or homemade pastrami, with Wisconsin muenster or Switzerland Swiss or Manchester creamy cheddar, and topped with applewood-smoked bacon or organic sunflower sprouts or honey mustard.

In the days before the rise of gourmand culture, before our obsession with purity and pesticides, before the most fetishistic of us could sit over plates of Humboldt Fog expounding on our favorite truffles or estate-bottled olive oil, Zingerman’s preached a new way of thinking about food: Eat the best, and eat homemade. Why choke down over-salted, processed chicken soup when you might slurp Zingerman’s rich stock, with its tender carrots and hint of rosemary? Why suffer any old chocolate when you might indulge in handcrafted, chocolate-covered clementines from some picturesque village in northern Italy, treats that exploded in your mouth, the citrus flooding in tingles across the tongue with the melted cocoa spreading beneath it, lifting and wrapping the clementine once again, but differently now, in the sweetest chocolate-orange cradle of sensory pleasure? Judging by the towering shelves of rare, five-star products from around the world—the quinces and capers, the salamis and spoonfruits, the sixteen-year-old balsamic vinegar and Finnish black licorice—the quest for higher and higher gustatory ecstasies never ceased.

If Zingerman’s preached a new way of thinking about food, it was by practicing the old ways, by trying to make latkes as they’d been made a hundred years ago, by returning to traditional recipes. The idea was to deepen the experience of eating by giving customers a sense of culinary history and geography, to ask questions like:

Why

are bagels round?