The Tiger Warrior (13 page)

Authors: David Gibbins

“There’s a reference to a book here, on the final page of the diary with writing on it,” Rebecca said. “It’s all smudged black.” She lifted the book and sniffed it, pulling a face. “It stinks like rotten eggs.”

“Black powder residue,” Jack said. “He must have had it on his hands when he wrote that. He’d have just been shooting. Look at the date. Twentieth August 1879.”

“I can barely read it, but the note says,

Campbell, Wild Tribes of Khondistan, page 177

. Then it says,

Lord help me.”

Jack took one of the two leather-bound volumes from the drawer and opened it to a marked page. “This is the actual book. He had it with him when he wrote that final diary entry. In the margin of the book he’s written,

Captain Frye, an admirable officer, an oriental scholar of the highest rank, who occupied himself most zealously in the acquisition of the Khond language

. He clearly wrote that some time earlier, perhaps when he’d first read the book before going into the jungle. But the passage of text beside the note is circled in the same ink as that last diary entry, slightly smudged. He must have read it again that day in the jungle. Listen to this:

“A curious circumstance occurred to this excellent officer when in the hills. He was informed one day of a sacrifice on the very eve of consummation; the victim was a young and handsome girl, fifteen or sixteen years old. Without a moments hesitation, he hastened with a small body of armed men to the spot indicated, and on arrival found the Khonds already assembled with their sacrificing priest, and the intended victim prepared for

the first act of the tragedy. He at once demanded her surrender; the Khonds, half-mad with excitement, hesitated for a moment, but observing his little party preparing for action, they yielded the girl Seeing the wild and irritated state of the Khonds, Captain Frye very prudently judged that this was no fitting occasion to argue with them, so with his prize he retraced his steps to his old encampment.”

“Human sacrifice?” Costas exclaimed, looking horrified. “India? In 1879?”

“That book was published in 1864, fifteen years before the Rampa Rebellion. The full title is

A Personal Narrative of Thirteen Years Service Amongst the Wild Tribes of Khondistan for the Suppression of Human Sacrifice

. The author, John Campbell, was an army officer charged with the task, and Frye was his assistant.”

“But they failed.”

Jack pursed his lips. “They succeeded. That was the public face of it, anyway. The British didn’t interfere much with ritual in India, but they drew the line at human sacrifice and female infanticide. What they did was drive both practices underground. Who knew what went on in the depths of the jungle, miles from prying eyes. Even today the sacrificial ritual survives among the tribal peoples, though they use chickens instead of humans. Or so we’re told.”

“And in 1879?”

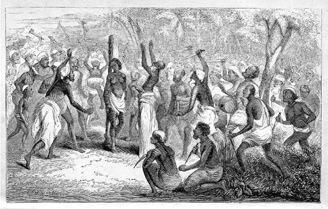

“The rebel leader, Chendrayya, openly executed several native policemen he’d taken captive, giving the executions the semblance of sacrifice in defiance of the British. On one occasion he used a sword, probably a

tulwar

like the one on the wall over there.” Jack opened the book to an engraving in the frontispiece. It showed a semi-naked woman tied to a pole with a priest in front and a crowd pressing around her, brandishing knives. “But there are hints that actual human sacrifice was also carried out. These involved a

meriah

, a man, or woman, even a child, who was bought into slavery by the sacrificing tribe, well-fed and well-treated for months in advance, then intoxicated with palm toddy and lashed to a stake.”

“How did they do it?” Rebecca asked quietly.

“It’s pretty unpleasant. They ripped the victim apart with their bare hands and knives. Each man took a strip of flesh home to bury in his own soil before nightfall that day as a kind of fertility offering.”

Rebecca looked pale. Costas took the book. “Why did they do it? Who was the god?”

“I’m coming to that.”

“And that date? Twentieth August 1879?”

“That’s the lynchpin date of the rebellion, and also somehow of Howard’s life. Something happened that day, something I’ve been trying to fathom out ever since I first saw the diary as a kid.” Jack picked up the diary. “Here’s what I know. On that day, a party of thirty sappers were led into an ambush by four hundred rebels, armed with bows and poison arrows and matchlock muskets, as well as some old company muskets they’d stolen from the police. The sappers fought their way back through the jungle to the river. It was one of the biggest fights of the rebellion, with dozens killed and wounded. One British official died, a civil service man responsible for this area who’d accompanied the troops. That day was big enough to hit the news, and was even reported in the London

Times

and

The New York Times

, with the name of the officer commanding the sapper party, Lieutenant Hamilton. His account of the fight was printed in the

Madras Military Proceedings

. Otherwise there are no eyewitness records of that day. But I’m certain something else happened.” “Executions?” Costas murmured. “Sacrifice?” Jack looked at the book. “Hamilton’s foray took place from a river steamer,

Shamrock

, which had been on its way upriver to a place where the sappers were going to hack a road into the jungle. Lieutenant Howard, my great-great-grandfather, was in overall charge, as the senior subaltern present. As well as Lieutenants Howard and Hamilton, there was another sapper officer, Robert Wauchope, recently returned from Afghanistan, an Irish-American who was a close friend of Howard’s. We’ve already encountered Dr. Walker, the Canadian. He probably had his hands full with cases of jungle fever. I’ve pinpointed where Hamilton’s party came out of the jungle on the riverbank, where the

Shamrock

must have been. It was the site of a native village. The rebels congregated there and put on a show for them. A pretty spectacular one. Howard was on the steamer. He saw something, or did something, that profoundly affected the rest of his life.”

“What do you mean?”

Jack paused. “He’d been at the top of his class at the Royal Military Academy, one of the officers flagged for great things, perhaps a future army commander like Lord Kitchener, another Royal Engineer. But after the jungle, it was as if he did everything he could to avoid active service again. He’d been detailed to join the Khyber Field Force in Afghanistan, but instead was deployed in Rampa until the end. Then he left the Madras Sappers for secondment to the Indian Public Works Department, and after that went back to England to spend ten years teaching survey and editing the journal of the School of Military Engineering. These were respectable career moves for a Royal Engineers officer, but not for the ambitious soldier he had once been. Even after he returned to India as a garrison engineer in the 1890s he passed up on chances of campaigning. It was only at the end of his career that he was poised for active service again, on the Afghan frontier, twenty-five years after the Rampa Rebellion.”

“What about devotion to his family?” Rebecca said. “Couldn’t that have influenced him?”

Jack looked across at the faded photograph above the chest, showing a woman in a black dress holding a baby, her faced turned down to the child, indiscernible. He turned to Rebecca, nodding slowly. “Howard married young, straight out of the academy. They had a baby boy they adored. They lived in the military cantonment at Bangalore, headquarters of the Madras Sappers. The boy died while Howard was in the jungle several months after that day in August, struck down with convulsions one morning and buried that evening. It was weeks before Howard even knew. His wife never got over it, though they had three more children. Howard was utterly devoted to them, and told his children that he took up his job at the School of Military Engineering in England to get them away from the diseases that had killed their brother, and to be with them when they were at school.”

“He put family before career,” Aysha said. “Nothing wrong with that.”

Jack pursed his lips. “But there was more to it than that. Even after they’d grown up and he’d returned to India, he passed up chances. I’m convinced something happened on that day, 20 August 1879.”

“Sounds like something traumatized him,” Costas said.

“There’s one other thing.” Jack leaned over and opened the lower drawer of the chest. “You remember I mentioned an artifact I’d spoken about to Katya, when she and I saw her uncle’s reference to the

Haljit Singh

, the Tiger Hand? The one that nearly made her faint? This was it.” He took out a gleaming brass object almost the length of his forearm, and placed it carefully on the table between them. It was semi-cylindrical, and one end had been formed into the shape of a head, with protruding ears and a wide, leering mouth. “Howard brought this back from Rampa. This, the revolver, the little telescope and a few primitive arms captured from the rebels are just about the only artifacts that can be pinned to the campaign. Any guesses what this is?” Jack asked.

Hiebermeyer pushed up his glasses and leaned over, lifting it up gingerly to look underneath. “Well, it’s clearly a piece of armor, for the lower forearm and hand,” he asserted. “In the hollow under the head there’s a crossbar, and the mouth has a hole in it the size of a blade. My opinion is that this was once a gauntlet with an attached dagger or sword blade.”

“Full marks,” Jack said. “Not a thrusting blade, but a long, flexible blade, for sweeping cuts. It would have been awkward in unskilled hands, but with the gauntlet and the crossbar, rather than a conventional sword handle, the blade would have become like an extension of the arm. The swordsman could deliver a massive sweeping blow, easily enough to slice bodies in half with a razor-sharp blade. They were fearsome weapons, designed to be used from horseback.”

Rebecca touched the nose. “Those eyes look Chinese.”

“It’s called a

pata

, a gauntlet sword,” Jack said. “This one’s unique, and only a few other brass ones are known. Steel

patas

were used by the Marathas, the warrior-princes the British fought in southern and central India in the eighteenth century. But the British scholar who first studied

patas

thought they originated much earlier, among the Tatar ancestors of the Mongols in northern China. They could have come into India with the Mongol invaders, with Timur the Great in the fourteenth century, or Genghis Khan. Or one might have come much earlier by way of the Silk Route and then been copied. Most of the Indian

patas

of the seventeenth or eighteenth century are made of steel, and don’t have this decoration, the hammered-out head. My instinct is that this one is older, much older, possibly even of ancient date.”

“So what’s the connection?” Costas said.

“You asked about the god, the sacrificial god in the jungle,” Jack replied. “There were several, one of them a kind of earth goddess, another a god of war. But there’s only one shrine we know of, and that’s to Rama, the god who gave his name to the district. The legend of Prince Rama is wrapped up in Hindu mythology, but the version of Rama worshipped in the jungle was distinctive, possibly of very early origin. The shrine is mentioned in the records of the Rampa Rebellion because the rebel leader Chendrayya sacrificed two police constables there. It lies directly inland from the point where the

Shamrock

picked up Lieutenant Hamilton and his sappers after their foray in the jungle. And I believe it was where my ancestor found this

pata

. It was the only permanent structure in the jungle other than the huts of the villagers, and exactly where you’d expect such an unusual object to be stored, even venerated.”

“And you want to go and check it out,” Costas said.

“I need to see what he saw. To see if there’s anything still left.”

“Rama,” Hiebermeyer murmured, tapping his fingers on the table.

“Rama”

“What is it?” Costas said.

“Just thinking aloud.”

Costas picked up the

pata

and stared at the face. “What is it? A god?”

Jack looked across. “It’s a tiger.”

“A tiger god?” Costas asked.

Jack slipped the

pata

over his hand, holding the crossbar. “Not tiger god,” he said, turning it slowly on his arm. “It’s what we always called it when I was growing up, what my grandfather told us to call it. He must have learned it from his grandfather, from John Howard. It’s what made Katya nearly faint when I described it to her.

Tiger warrior.”

Early the next morning they stood on the bridge wing gazing out over the bows of the ship.

Seaquest II

had passed through the Palk Strait between India and Sri Lanka, navigating the treacherous channel at only a couple of knots speed. They had just watched the pilot disembark and power off in his speedboat. The northern tip of Sri Lanka was now receding off the starboard stern quarter, and the captain had reduced the alert level as they entered Indian territorial waters. The Breda gun turret had been lowered out of sight below the foredeck and the security team were stowing the two general purpose machine guns, which had been mounted on either side of the bridge. Ahead of them lay the Bay of Bengal, a shimmering expanse of water seemingly stretching out to infinity. The sea was dead calm, and it was as if they were motionless, mired in a haze of sea and sky with no visible horizon.